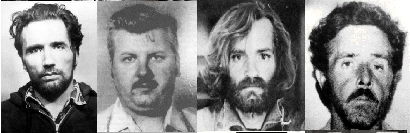

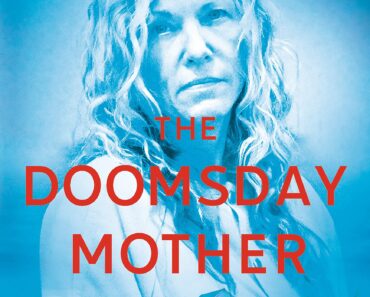

Tsutomu Miyazaki | Serial Killer

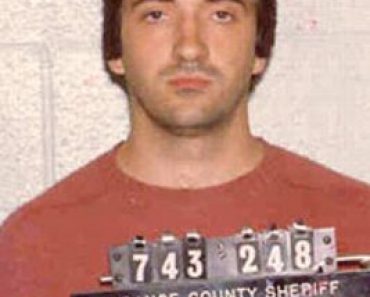

Tsutomu Miyazaki

Born: 08-21-1962

The Little Girl Killer

Japanese Serial Killer

Crime Spree: 1988–1989

Executed on 06-17-2008

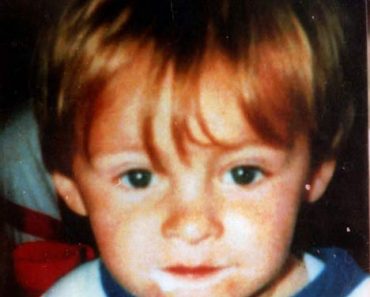

Shortly after 3 pm on August 22, 1988, four-year-old Mari Konno left her home in the Iruma Village apartment complex in Saitama to play at her friend’s hours. At 6:23 pm, after she failed to return, architect Shigeo Konno, struggling to quell his panic, called the police to report that his daughter was missing. About the same time as Konno’s phone call, in a dark forest 50 km away, Mari was being slowly strangled to death.

As Mari made her way through the complex earlier that afternoon, a Nissan Langley sedan had pulled up nearby, and a man had climbed out of the driver’s seat. “Wouldn’t you like to go somewhere where it’s cool?” he asked. Mari nodded and taking his hand, skipped towards the car.

While Mari played happily with the buttons on the radio, the car purred down National Highway No. 16 toward Hachioji in western Tokyo. Just before reaching Musashino Bridge, it swung right onto a road leading towards Itsukaichi. An hour and a half after it had left Iruma Village, the car came to a halt on a narrow dirt road in the woods near the Shintama power station, which loomed like a mammoth gravestone above the trees.

The man and Mari got out of the car and walked down a mountain path fringed by hinoki and sugi trees to where the hiking trail toward Komine Pass begins. The cicadas were in full cry and the mountain doves cooed in the stifling heat. After 20 or 30 minutes, the two sat down at a spot some 20 meters off the path.

The Murder Of Mari Konno

Mari was tired; she might also have been frightened, because she began to sniffle. The man panicked. What if she started to bawl? The hiking course was a popular one, and someone might hear. But he had no intention of returning her to her parents.

While Mari’s face froze in surprise, the man put his hands on her throat, thumbs on the larynx, and squeezed the life from her tiny body. When she finally went limp, he reverently undressed and fondled her. Then he laid her out as if in repose, bundled up her shorts, panties, shirt, and shoes, and walked, unnoticed, out of the forest and back to his car.

So ended the brief life of Mari Konno. And so began the murderous career of Tsutomu Miyazaki, a 26-year-old printer’s assistant. By the time he was arrested, Tsutomu Miyazaki had strangled and sexually abused three other young girls, terrorized a whole prefecture, and for 11 months, evaded an unprecedented police hunt for the man responsible for “The Little Girl Murders.”

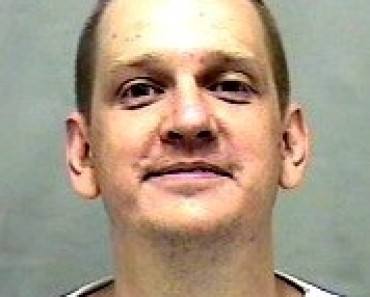

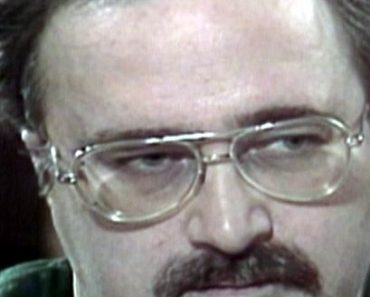

Apprehending Tsutomu Miyazaki

When the police finally apprehended Tsutomu Miyazaki, they entered his home to find 6,000 videotapes of kiddy porn, splatter flicks, and cartoons. Among the grisly collection were videos and photos of his victims. It was evident that, for Miyazaki, his killing spree was little more than an extension of a lonely fantasy world. “It was like a game to him–a one-man play,” said Akira Ishii, a law professor at Aoyama Gakuin University and psychotherapist who followed the case closely. The case of Tsutomu Miyazaki, Interprefectural Felon No.117, ground its way through the courts. This fall (1993)the psychological evaluation that should finally decide Miyazaki’s fate–and lay to rest the ghosts of four murdered girls–will be announced. This is the second time the court has ordered an investigation into the crucial question: Is Tsutomu Miyazaki mad or bad? The answer will dictate whether or not Miyazaki is held criminally responsible for his crimes and will decide his sentence. “Miyazaki’s crimes were thrill killings of a rare kind,” concluded Dr. Susumu Oda, a psychologist at Tsukuba University. “Yet you could call him a textbook case.”

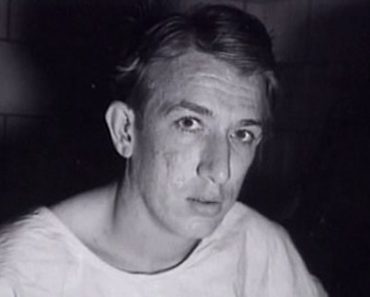

The text of Tsutomu Miyazaki’s life began in Itsukaichi, Tokyo, on August 21, 1962, where he was prematurely born. He weighed only 2.2 kg, and the joints in his hands were fused together, making it impossible for him to bend his wrists upwards. The deformation haunted him from early on. When he was five years old, a classmate teased him about his “funny hands.” In family photos after that, Tsutomu Miyazaki never showed his hands, and his eyes were often closed.

Tsutomu Miyazaki

By the time he reached Itsukaichi Elementary School, Tsutomu Miyazaki was almost invisible. When he is remembered at all by teachers and classmates, it is as a quiet, lonely child who seemed utterly incapable of making friends. But young Tsutomu, like any other boy, did have dreams; in the third grade, he wrote an essay: “When I grow up, I want to buy a car and go driving. I’ll stop at a restaurant and eat some curry rice or something. I might even visit my relatives.” More often than not, however, he increasingly blamed his deformed hands for his inability to achieve anything concrete. He began to stay up into the night reading comic books.

Tsutomu Miyazaki was clearly a clever child. Locked in his own isolated world, he studied hard, and became the first student from his junior high school to pass the entrance exam to Meidai Nakano High School. He commuted two hours each way, every day, for three years, but eventually began to lose interest in his studies. Instead of joining his fellow students, Tsutomu Miyazaki would retreat to a quiet corner to work on another home-drawn comic book. His plan–to enter Meiji University (with which the high school was affiliated), major in English and become a teacher–was over by his final year, when he ended up 40th in a class of 56, with grades so poor that he failed to receive the customary recommendation to the university. Naturally, he blamed his handicap.

Junior College

Tsutomu Miyazaki settled for a photo-technician’s course at a junior college and, after graduation in the spring of 1983, went to work at a printing plant owned by an acquaintance of his father. After thee years, during which he saved more than 3 million yen, he moved back to the family home, where he shared with his eldest sister a two-room annex to the main house near his father’s printing business. Known around town for his unfailing courtesy, Katsumi Miyazaki owned the _Akikawa Shimbun_, a major local newspaper in the Itsukaichi area, Tokyo’s most inland point. There, the Miyazaki family had considerable political influence.

The family had little influence over Tsutomu, however. His workaholic father was more interested in collecting political video clips and the latest cameras–enthusiasms that would echo grimly in his son’s crimes. Miyazaki’s mother Rieko also worked, but tried to compensate by buying Tsutomu gifts, such as the Nissan Langley sedan in which two of his victims died. “If I tried to talk to my parents about my problems, they’d just brush me off,” Miyazaki confessed to police. “I even thought about suicide,” he said.

Miyazaki’s two younger sisters, Setsuko and Haruko, merely found him repulsive. Only his grandfather Shokichi, a widely regarded man who had served on the city council, seemed to take a genuine interest in the boy.

Tsutomu Miyazaki

Miyazaki avoided women his own age, perhaps because he was physically immature. “His penis is no thicker than a pencil and no longer than a toothpick,” a high-school classmate remarked. Yet his sex drive was stronger than average. At college, he took his still and video cameras to the tennis courts to take crotch shots of female players. He also soon tired of adult porn magazines. “They black out the most important part,” he complained. So, by 1984, he had turned to child porn, which shows everything, since obscenity laws ban the showing of pubic hair, not sex organs.

“As a boy, he made no close friends and therefore gained no information about sex in the real world,” said Oda. “Instead, he turned to videos, comics, and pornography for his thrills.” Oda also believes that Tsutomu Miyazaki thought himself important because of his small penis and deformed hands.

How then did Miyazaki’s unnatural vices lead him to kill? As Prof. Ishii at Aoyama Gakuin University pointed out, “People grow up in similar environments yet never become murderers.”

The Trigger

The trigger seems to have been the death of his grandfather in May 1988, three months before the first murder. His grandfather had been his only warm adult relationship, and the death marked the breaking of Miyazaki’s last bonds with society. Tsutomu Miyazaki later said that he even ate some of his grandfather’s cremated bones–a claim that Shunsuke Serizawa, a literary critic and witness for Miyazaki’s defense, believes. “He wanted to reincarnate his grandfather, and believed that this reincarnation would not be complete if any of his grandfather’s body remained,” Serizawa said.

His grandfather’s demise also complemented Miyazaki’s estrangement from his family. Once, when his youngest sister yelled at him for peeking at her in the bath, he burst in and smashed her head against the bathtub. Later, when his mother suggested he spend more time at work and less with his videos, Miyazaki exploded and beat her. Miyazaki’s father had long since given up trying to talk to him.

“I felt all alone,” Tsutomu Miyazaki explained later. “And whenever I saw a little girl playing on her own, it was almost like seeing myself.”

The Investigation

The first of those little girls to die from Miyazaki’s attentions was Mari Konno. After her disappearance, police squad cars with loudspeakers patrolled the streets warning parents to keep their children in sight at all times. Although it was officially tagged as a missing person case, “the police started the investigation as a murder right from the beginning,” said a journalist who followed the Miyazaki case.

Eventually, the police spent 2,930 man-days interviewing people around Mari’s home and sent 50,000 posters with Mari’s picture to police, train, subway, and bus stations across the nation. Nothing came of these efforts. Not even police dogs could pick up the girl’s scent.

Two boys said they had seen Mari walking behind a man toward the nearby Iruna River, and the _Asahi Shimbun_ interviewed a 38-year-old housewife who had spotted Mari with a stranger. Apart from the age, the description was accurate: late thirties, about 170 cm tall; face: round and pudgy with curly hair; clothes: white slacks and a white summer sweater. There was only one other potential clue. A few days after Mari disappeared, Yukie Konno, Mari’s mother, received a postcard with a haunting message after she had expressed hope in a news bulletin that her daughter was still alive. “There are devils about,” it read. The police dismissed the note as the act of a crank.

The fruitless hunt for Mari Konno eventually dwindled after four weeks. In September, Sayama Hikari Gakuen Kindergarten began its new term without her. Since the police had received no demands from a kidnapper and found no body, her file, categorized under _missing persons_, lay dormant. But many parents in the area were taking no risks. “From the time Mari disappeared until Tsutomu Miyazaki was caught, parents led their children to kindergarten every day,” recalled one mother.

Tsutomu Miyazaki Strikes Again

Six weeks after Mari’s disappearance, Miyazaki struck again. Driving through Hanno, Saitama Prefecture, on the afternoon of October 3, 1988, he spotted Masami Yoshizawa, a seven-year-old first-grader, walking along the roadside. He coaxed her into his car, drove to the hills above Komine Pass–the scene of his first murder–and strangled her to death. Then he stripped her–quickly, before rigor mortis set in–and sexually abused the corpse.

When the little body shuddered involuntarily, Miyazaki, frightened, ran back to his car and drove off. He left her remains less than 100 meters from where the bones of Mari Konno lay whitening in the sun.

After she was reported missing later that night, local search parties fanned out across the area. Soon Masami’s face stared down from hundreds of posters issued by the police, who subsequently spent over 2,300 man-days interviewing local residents. Again, no clues to the girl’s whereabouts were found. Masami’s home is only 13 km from Mari’s. The police were suspicious enough to compare the two cases, but had neither leads nor bodies. Masami, too, was declared a missing person.

Killing Masami had upset Tsutomu Miyazaki, but he would kill again before 1988 was over. The December 12th murder of a four-year-old from Kawagoe, however, would be different. First, Miyazaki would nearly be caught. Second, the body would be discovered soon after the act, setting off a murder hunt that would compel police to reassess the disappearance of Mari and Masami, and confirm the worst fears of many Saitama residents: that there was a serial child killer on the loose.

No Concern For Life

Tsutomu Miyazaki never displayed much concern for life. “I’ve killed cats,” he later said casually. “Threw one in the river. Did another in with boiling water.” He also throttled his own dog to death with a strand of wire. His absorption in a video world, explains Oda, “removed his consciousness from reality. Everything became an item to him, including people. The little girls he killed were no more than characters from his comic-book life.”

Erika Namba was returning from a friend’s house when Tsutomu Miyazaki lured her into his sedan. She was crying by the time he pulled into the parking area at the Youth Nature House in Naguri. He told Erika to undress in the back seat, then began to photograph her, the strobe flashing in the dark.

A car drove by, its headlights sweeping momentarily across Miyazaki’s face. Erika began sobbing again. Miyazaki grabbed her by the throat and straddled her, holding her kicking body down with his weight as he strangled her. By 7 pm, his third victim was dead. Tsutomu Miyazaki carefully wrapped the body in a sheet and put it in the trunk. Then he disposed of her clothes in the woods behind the parking area and drove off. Miyazaki’s mind clearly wasn’t on the road. As he turned a corner, one of the Langley’s front wheels slipped into the gutter; the car was stuck. So he switched on the hazard lights, and disappeared into the dark woods with the sheet-wrapped body in his arms. He returned with the crumpled sheet to find two men standing by his car. Casually opening the trunk to put the sheet away, he explained his problem to the men, who then helped lift the car out of the rut. Miyazaki got in, and without a word of thanks, sped away.

The Connection

This time, the Kawagoe police immediately connected Erika Namba’s disappearance with that of Mari Konno and Masami Yoshizawa, and the Saitama prefectural office set up a special operations center to solve the three _missing persons_ cases. The next day, a worker at the Naguri Youth Nature House found some of Erika’s clothes, and hundreds of police began combing the area. Meanwhile, the PTA at Erika’s kindergarten pasted handbills around the apartment complex where the Namba family lived.

Police found Erika’s corpse the next day, its hands and feet bound with nylon cord. The murder scene was 50 km from Erika’s home, a journey of about an hour and forty-five minutes. Five hundred riot police explored the woods for more clues, but found nothing.

The two men who had helped Tsutomu Miyazaki with his car on the night of the murder came forward to identify it. They correctly recalled that the car had Hachioji plates, but misidentified the model as a Toyota Corolla II–an error the police realized only after they had checked out more than 6,000 Corolla IIs. This blunder deprived investigators of what could have been their strongest lead.

Seen in the macabre light of the recovery of Erika’s body, the disappearance of Mari and Masami pointed strongly toward a more serious crime. All the girls were from Saitama Prefecture; all lived within 30 km of each other. “As soon as they found the body of the third girl, they began to treat it as a serial murder case,” said a police journalist.

Strange Calls

Police found that the families had something else in common: they had all been bothered by strange phone calls. The phone would ring, but when answered, the person on the other end would say nothing; if they didn’t pick up it up, the phone would ring for up to 20 minutes.

And, less than a week after his daughter’s murder, Shin’ichi Namba, like the Konnos, received a postcard. It was formed from kanji characters cut from magazines and newspapers, then photocopied and enlarged to conceal their origin. It read: “Erika. Cold. Cough. Throat. Rest. Death.”

The hunt for Mari and Masami led nowhere. No clues were unearthed that shed light on Erika’s murder. Hardly a day passed when television reports didn’t cover the cases. After the discovery of Erika’s body, the atmosphere of apprehension among Saitama’s parents and teachers turned to alarm. An _Asahi Shimbun_ editorial at the end of 1988 caught the mood of subdued panic. “In the end,” it read, “we must depend on the police . . . . So se add our plea: investigators, redouble your efforts.”

Tsutomu Miyazaki Was Not Finished Yet

Miyazaki would not kill again until the following summer. But he was still busy. At about 6 am, on his way to work on February 6th, Shigeo Konno, Mari’s father, found a box on his doorstep and called the police. Along with ashes, dirt, fragments of charred bones, and 10 baby teeth, it also contained photos of a child’s shorts, underwear, and sandals–and a single sheet of copier paper with five words on it: “Mari. Bones. Cremated. Investigate. Prove.” Tsutomu Miyazaki had returned to the death site, as he had done several times, and removed the remains.

The 10 small teeth found among the ashes were immediately turned over to the legal division of the Tokyo Dental University for examination, where Dr. Kazuo Suzuki concluded the probably did not belong to Mari. After a police press conference announced this finding, Suzuki changed his mind, to the agony of the Konno family. His examination was mistaken, he said; the remains might be Mari’s after all. Then a police forensic expert gave his verdict on the 220 grams of bone fragments: they were not only human, they were Mari Konno’s.

Tsutomu Miyazaki, avidly following news reports, heard only the original verdict–that the teeth were not Mari’s–and immediately sat down to write. On February 11th, a three-page letter arrived at the Konno home. The society desk of the _Asahi Shimbun_ also received a copy, along with a Polaroid-type photo of Mari. The letter was entitled “Crime Confession” and signed “Yuko Imada,” a pun on “Now I’ll tell.”

Tsutomu Miyazaki

“I put the cardboard box with Mari’s remains in it in front of her home,” it began. “I did everything. From the start of the Mari incident to the finish. I saw the police press conference where they said the remains were not Mari’s. On camera, her mother said the report gave her new hope that Mari might still be alive. I knew then that I had to write this confession so Mari’s mother would not continue to hope in vain. I say again: the remains are Mari’s.”

The confession caused an uproar. The next day, the Saitama police finally classified the Mari Konno case as a homicide, and set up a special center to investigate her abduction and murder. Handwriting experts examined the confession note but could not establish the author’s sex. Over a half million police leaflets quoting the confession were delivered to houses in the areas where the girls lived.

The police did, however, correctly identify the snapshot of Mari as one taken with a Mamiya 6×7 camera “like those used by printers”–another clue that was perhaps inadequately followed up; they also rightly concluded that the box was the double-walled corrugated kind often used to ship camera lenses. The typeface on the postcards was determined to have come from a phototypesetter, and copied on an industrial copier. Police later refused to comment on whether or not they launched an investigation of printing shops in the area.

The Nightmare Wasn’t Over

The Konnos waited three weeks before the police officially announced that the box contained the remains of their daughter. The box contained almost an entire skeleton of a four- or five-year-old girl; and two of the teeth matched perfectly with X-rays of her dental work. On March 11, 1989–over seven months after she was declared missing–Mari was laid to rest. “Her hands and feet didn’t seem to be with the remains,” said Shigeo Konno at the funeral. “When she gets to heaven, she won’t be able to walk or eat. Please return the rest of her remains.”

The Konnos returned home from the funeral to find another letter from “Yuko Imada.” This one, labeled simply “Confession,” chronicled the changes Tsutomu Miyazaki had observed in Mari’s dead body: “Before I knew it, the child’s corpse had gone rigid. I wanted to cross her hands over her breast but they wouldn’t budge. . . . Pretty soon, the body gets red spots all over it . . . . Big red spots. Like the _Hinomaru_ flag. Or like you’d covered her whole body with red _hanko_ seals. . . . After a while, the body is covered with stretch marks. It was so rigid before, but now it feels like its full of water. And it smells. How it smells. Like nothing you’ve ever smelled in this whole wide world.”

In spite of hints offered by “Yuko Imada,” the police were unable to pick up Miyazaki’s trail. Some observers have interpreted the letters as Miyazaki’s gloating at the society that he felt had shunned him. Prof. Akira Ishii disagrees: “None of it had any social meaning for him. It was just like playing a video game–you know, ‘plus one point for causing a sensation.’ He wasn’t trying to gain society’s recognition. He had a society in his mind, of which he was the nucleus.”

Victim Four

By the summer of 1989, Tsutomu Miyazaki was growing restless. He skipped work more often to spend hours sitting cross-legged in his room, editing his precious videotapes. On the first day of June, he saw girls playing near the Akishima Elementary School, and coaxed one of them to take her panties off. As he began to photograph her, some neighbors spotted him and chased him off. Despite this close call, Miyazaki butchered his fourth victim five days later.

On June 6th, Tsutomu Miyazaki left his bungalow for the tennis courts at Ariake, near Tokyo Bay, but the courts were closed. In a nearby park, he found five-year-old Ayako Nomoto playing alone. Casually removing the lens cap from his camera, Miyazaki approached Ayako and asked her to pose for pictures. He then took several shots until Ayako got used to him. “Let’s take some shots inside the car,” he coaxed, leading her to his Langley.

Miyazaki parked some 800 meters away as Ayako bounced in the back seat. As he handed her a stick of gum, the young girl commented on his deformed hands. Enraged, Tsutomu Miyazaki pulled on a pair of vinyl gloves. “Here’s what happens to kids who say things like that,” he growled, seizing her by the throat. “She kicked and kicked, but went limp in four or five minutes,” he later confessed. To make sure she was dead, he taped her mouth and tied her hands with vinyl rope, then wrapped the body in a sheet and put it in the trunk of the car.

Tsutomu Miyazaki

This time, he took the body home, stopping at a video shop in Koenji to rent a camera. The house was dark when he parked next to the two-room bungalow. He waited two hours, then carried the tiny corpse inside, where he stripped off the clothes and wiped it with a towel. He laid it on the low _kotatsu_ table, spread the legs and taped the vagina apart. He then took photographs and videos while he masturbated. Afterwards, he bound up the hands and feet again with nylon cord and covered the body with three sheets.

Two days later, the odor of the decomposing corpse became unbearable. Although he was right in believing that police were nowhere near identifying him as the “Little Girl Murderer,” Tsutomu Miyazaki knew he had to dispose of the body. With a knife and a saw, he hacked off the cadaver’s head, hands, and feet to hamper identification. Then he hid the torso near the public toilet at Hanno’s Miyazawa-ko cemetery at midnight, four days after the murder. He roasted Ayako’s hands in his back yard, ate some of her flesh, and tossed what remained, including the skull, into the woods of Mitakeyama, a 230-meter hill in front of his house.

Realizing the risk of having the remains so near his home, he retrieved and hid them two weeks later in a bag in the storeroom behind his bedroom. Later, he scattered the bones in the woods, then burned the hair, the clothes, and the blood-stained plastic bags and sheets.

Desperate To Find A Serial Killer

Five days later, after police had distributed 10,000 handbills with Ayako’s description and picture, the little girl’s mutilated torso was discovered at the cemetery. Despite Miyazaki’s butchery, the remains were quickly identified. The blood type and chest size matched those of Ayako Nomoto, reported missing by her mother at 8:40 pm on June 6th. The stomach contents matched Ayako’s last meal.

In the end, Miyazaki’s gruesome career was cut short by a citizen, despite the massive police forces pitted against him.

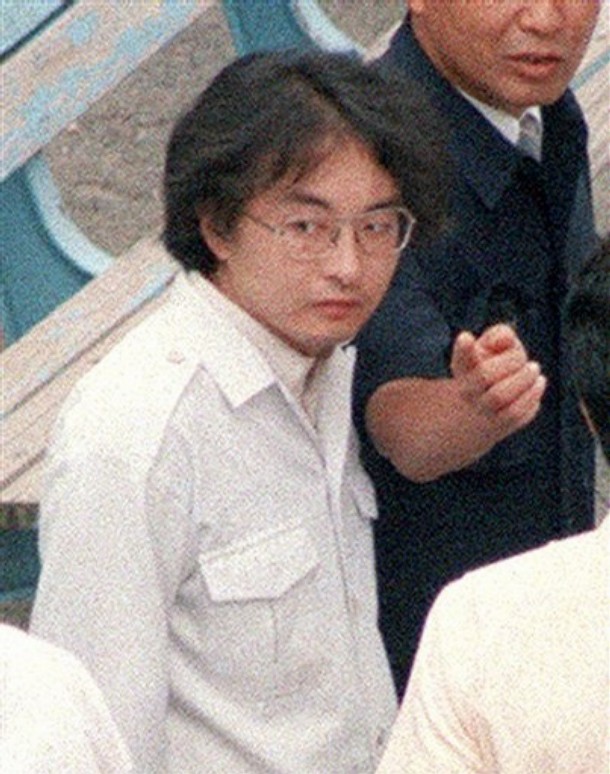

On Sunday, July 23, 1989, two sisters were playing near a public washstand in Hachioji, when a young man stopped his car and got out. “You stay here,” he told the elder nine-year-old, cajoling the younger child toward a nearby river. But the older sister ran home for her father, who sprinted back to find his daughter naked, with a young man focusing a camera between her legs. He grabbed him and knocked him down. The man twisted away and ran to the swampy edge of the river to escape. Then, incredibly, he returned to his car where the Hachioji police, who had already been called, apprehended Tsutomu Miyazaki on the charge of “forcing a minor to commit indecent acts.”

The police clearly believed they had found their serial killer. One Saitama housewife remembers how house-to-house police questioning in her apartment complex ended abruptly on the day the news broke, though nothing was officially revealed of the suspect’s involvement in other crimes. “Even then, television reports were saying he was the serial killer,” she recalled. The news media were so convinced that Tsutomu Miyazaki was the man that they beat the police to the Miyazaki home, where they filmed Tsutomu’s room.

Tsutomu Miyazaki Confesses

Seventeen days later, Miyazaki confessed to murdering Ayako nomoto, whose skull was found the next day in the hills of Okutama. The other confessions followed swiftly: first, the murder of Erika Namba; then Mari Konno, of whom video clips were discovered among the 6,000 tapes in Miyazaki’s lair. By mid-September, after a preliminary psychological test by NPA psychiatrists concluded that Miyazaki showed “No immediately apparent disorders,” he confessed to the fourth of the “Little Girl Murders.”

On September 6th, Masami Yoshizawa’s remains were found in the forest near Komine Pass, Itsukaichi. The half-chewed bones of Mari Konno’s hands and feet were discovered nearby a week later. Her father’s plea for the return of his daughter’s hands and feet had finally been answered.

Could the police have tracked down Tsutomu Miyazaki sooner?

Until Miyazaki’s arrest and subsequent confessions, the police were far from identifying the murderer, despite an intense and costly investigation. “It’s almost impossible to catch a murderer when there’s no relationship between them and the victims,” a police journalist explained. “It becomes just a matter of luck.” In Erika’s case alone, more than 600 calls from the citizens of Hanno kept the police occupied for days.

What if the National Police Agency had got involved sooner?

Then, as when the FBI moves in, all information would have been immediately relayed from local police to a national center; the NPA would have also helped foot the mammoth bill for the manhunt. But the NPA’s sphere of influence dictated that it could not get involved until an incident occurred in Tokyo. The NPA did set up a missing persons team after Ayako went missing in Tokyo, but this, according to an NPA source, does not constitute an investigation. The NPA’s real involvement began only when Miyazaki started confessing.

Miyazaki’s father refused to hire a lawyer for his son. “It wouldn’t be fair to the victims,” he said. The public defender’s office looked long and hard before finding two lawyers, Junji Suzuki and Keiji Iwakura, who were willing to take the case. Suzuki agreed because of his vehement opposition to the death penalty.

The defense team’s case revolves around the claim that Tsutomu Miyazaki has only limited sense of responsibility for his crimes, that he is unable to choose between right and wrong. “We want to build enough of a case for the judge to sentence Miyazaki to life in prison,” said Suzuki. The court’s first action was to assign a team of six psychology professors from Keio University to examine Miyazaki. Last year, they filed their report: Tsutomu Miyazaki was fully capable of taking responsibility for his actions. Attorney Suzuki disagrees.

A Different World for Tsutomu Miyazaki

“The more we see of him, the more we think he lives in a different world,” said Suzuki. “We felt the report did not establish Miyazaki’s mental capabilities beyond reasonable doubt, so we asked for a second evaluation. Fortunately, the judge agreed.” Late last year, a team of three Tokyo University professors began the evaluation of Tsutomu Miyazaki that is due this autumn. “It is very unusual for a team to evaluate a defendant,” Suzuki added. “Usually, a single psychologist is used.” This will be the defense team’s last appeal. The prosecution can appeal for another evaluation if it disagrees with the upcoming report: the defense cannot.

There are three possible outcomes to the psychological evaluation. If the second report agrees that Tsutomu Miyazaki is mentally incompetent, he will be sent to a mental institution where, if precedent is followed, he’ll be released in 12 or 13 years. However, public prosecutors, who have over 750 items of physical evidence, have no intention of letting Miyazaki loose. They will surely petition the court for a third testing, and a fourth, until–in theory–Tsutomu Miyazaki is as dead as his victims.

The second possibility–the result Suzuki seeks–is that Miyazaki will be judged to have a limited sense of responsibility for his crimes. “He may not have an incapacitating personality disorder such as paranoia or schizophrenia, but I think he may be borderline,” said Suzuki. “We hope the psychological team agrees.” This result, thinks this result will earn Miyazaki a life sentence without parole. Prof. Ishii expects the same psychological outcome, but believes Miyazaki’s life sentence will, in effect, last about 12 to 15 years. “It is impossible to say whether he will still be dangerous by then,” said Ishii. “However, keeping him in prison for the rest of his life raises other questions of human rights.”

A Way Of Possessing Them

The third possible outcome is that Miyazaki is deemed mentally competent enough to take full responsibility for his crimes. In this case, the judge would have no choice but to condemn him to death. Although Suzuki cannot appeal the psychological evaluation, he can–and would–appeal a death sentence.

Nobody involved in the case doubts that Tsutomu Miyazaki is a very, very disturbed young man. Dr. Oda lists a grab bag of obsessions: pedophilia, necrophilia, sadism, fetishism, and cannibalism. Prof. Ishii believes Miyazaki was a pedophile first, a murderer second. “Killing was an extension of his interest in little girls, a way of possessing them,” he said.

But is Tsutomu Miyazaki insane? “I don’t see how Miyazaki could be judged responsible for his actions,” said Shunsuke Serizawa. “He shows no signs of being aware of being aware of the gravity of his crimes. He has no sense of guilt. Even the judge seems to agree that his first psychological testing was very inadequate, which is why a second testing was ordered.” But, although he strongly believes that Miyazaki should not be held criminally responsible for his deeds, Serizawa stresses that “it still would not do to let him loose in society.” Miyazaki’s lawyer echoes this sentiment. “The defense team will do its best to see that he gets life,” Suzuki said.

Happy Man

Next month Tsutomu Miyazaki will celebrate his 31st birthday in prison. “He’s perfectly happy,” said Suzuki. “He is allowed to read comic books all day.” As they near a decision, the Tokyo University psychologists observe their subject every day. Yet, Suzuki claimed, Tsutomu Miyazaki barely registers the fact that people are staring at him. “He hates that,” said Suzuki. “He’s very self-conscious.”

All that remains of the Itsukaichi house and printing plant complex is an open lot and the small two-room annex where Miyazaki slept among his teetering stacks of gruesome video tapes. Miyazaki’s parents, who visit once a week to replenish his supply of comics, shut down the _Akikawa Shimbun_, and went into hiding soon after their son’s confessions were made public. In a 1989 interview with the _Tokyo Shimbun_, Katsumi Miyazaki regretted that “I didn’t pay more attention to the feelings of my son.” After his arrest, Tsutomu Miyazaki had written a furious letter to his father, blaming him for everything.

To his mother, however, Miyazaki was more conciliatory. “Mother, I’ve caused you much heartache,” he wrote once. Then he added, “Don’t forget to change the oil in my car, or it will get so you can’t drive it.

Afterword

Tsutomu Miyazaki was judged to have multiple personalities at the least and schizophrenia at the worst by the Tokyo University psychologists. It didn’t matter. He was sentenced to death on April 14, 1997 and executed by hanging on June 17, 2008

His father committed suicide.

source: murderpedia / Charles T. Whipple