Wayne Williams | Child Serial Killer

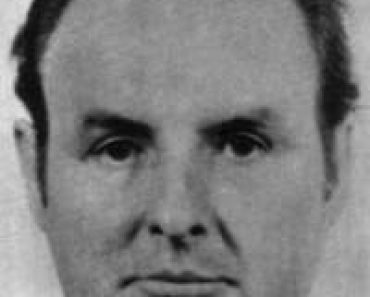

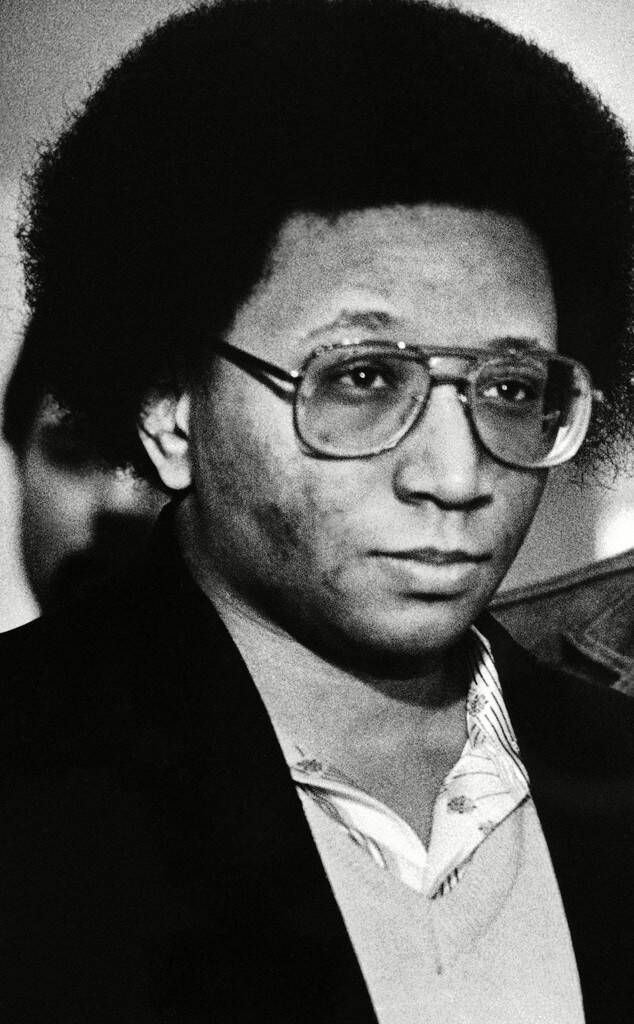

Wayne Williams

Born: 05-27-1958

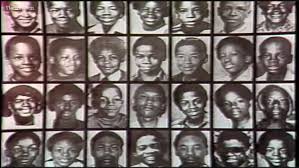

The Atlanta Child Murders

An American Serial Killer

Crime Spree: 1976 – 1981

Incarcerated at Telfair State Prison, Georgia

Wayne Bertram Williams was born on May 27, 1958. He was raised in the Atlanta Dixie Hills neighborhood, from which many of the Atlanta Child Murder victims would later disappear. He was an aspiring DJ who ran an amateur radio station from his parents’ house. He was well-known in the area for scouting local musicians, particularly teenagers. He had a reputation as a liar who invented impressive stories about himself and it was rumored he was gay. Prior to becoming a murder suspect in the Atlanta Child Murders, in 1976, Wayne had had no run-ins with the law.

Is Wayne Williams Guilty

Setting the Stage

In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the city of Atlanta, Georgia, had grown into an economic powerhouse in the South. Long developing as a major regional transportation center, the city had also boasted a number of major corporations, such as Coca Cola, Delta Airlines, and Cox Communications.

The increasingly black population in the city voted into the mayor’s office one of their own race, a young lawyer named Maynard Jackson. For Jackson, keeping a power-balancing act between his black constituency and the existing white power structure was critical. Otherwise, the white power structure would flee to the suburbs, leaving the city with a much diminished tax base.

Despite the strong economic growth, the black population of the city remained very poor. Not surprisingly, a serious crime problem developed that made Atlanta one of the most dangerous cities in the country. Atlanta’s business community was alarmed at the spiraling crime rate, fearful that businesses would flee the city and conventions would find safer cities for their meetings.

In a four-month period, two very high profile street murders of whites by blacks would crystallize their fears. On June 28, 1979, a young white doctor attending one of the city’s conventions, was murdered by two black robbers. Then on October 17, 1979, a mentally unstable black man gunned down a white legal secretary on her birthday. Everyone was outraged and the media demanded a crackdown on crime.

In 1978, Mayor Jackson had replaced his controversial black public safety commissioner Reginald Eaves with Dr. Lee Brown, who was an intelligent, capable manager but had very limited street experience and was perceived as socially distant from the poor black community.

Little did the city understand that these two highly publicized crimes would be dwarfed by two other crimes which, when they happened, received almost no publicity at all. Two black boys were found murdered at the end of July 1979, officially starting one of the most highly publicized murder series in history. A couple of years later, twenty-nine black youths would be dead and a black man, who many people believe was railroaded by the government, would be imprisoned for life.

Ominous Beginning

Fourteen-year-old Edward Hope Smith lived in one of Atlanta’s lower income housing projects on Cape Street in southwest Atlanta. It was a destitute place that many had the misfortune of living in and few had the means to escape, even though Edward had tried. It isn’t difficult to understand why anyone would want to run away from such a disheartening place where more garbage filled the streets than people. Just after midnight in the early morning hours of July 21, 1979, Edward left a skating rink where he had spent the evening with his girlfriend and began the long walk home.

Several days later, his friend, fourteen-year-old Alfred Evans, who lived on the other side of town off Memorial Drive in the East Lake Meadows housing projects, left home to see a karate movie in downtown Atlanta.

Both boys were very athletic. Smith was a football fanatic and Evans was equally exuberant about basketball, professional wrestling, boxing and karate. Smith was training to play on the high school football team in the fall and Evans played basketball and boxed. These boys had promise, despite their disadvantaged status. And they had dreams that they were enthusiastically pursuing.

Those dreams however quickly became nightmares when Edward never got home from the skating rink that morning and Alfred didn’t make it to the karate movie. Instead, both of them were found on July 28 in a wooded area off Niskey Lake Road in the southwestern part of the city. Edward had been killed with a.22-caliber gun and Alfred by an undetermined means. The medical examiner guessed at asphyxia, possibly resulting from strangulation. Both boys were dressed in black, but Edward’s socks and distinctive football shirt were missing. Alfred was wearing a belt that wasn’t his. Edward was easily identified with dental records, but Alfred’s identification is still debated.

What happened

Police determined that both boys had at least some involvement with drugs and were possibly together at a pot party. One caller claimed that Alfred shot Edward and a third boy strangled Alfred in a fit of rage. These stories did not work well with the difference of days between their disappearances, nor did the caller ever show up to make a formal statement. That’s really all the police needed to hear: black boys involved with drugs (no matter how tangentially) was sad, but it was also quite common. Further investigation into the deaths was very limited.

While the police may have been able to get away with dismissing the deaths of Smith and Evans as “drug-related,” it was certainly not the case with fourteen-year-old Milton Harvey. His parents had extricated Milton from the high-risk projects years ago and moved him to a pleasant middle-class neighborhood in northwest Atlanta. He didn’t go to school on the first day of the session because his mother had inadvertently bought him the “wrong” kind of sneakers and he couldn’t face the embarrassment. That day, September 4, 1979, Milton borrowed a bike and took a check to the bank to pay a credit card bill for his mother. He disappeared, along with the bicycle, which was found a week later on a deserted dirt lane named Sandy Creek Road.

Milton’s badly decomposed remains were found in mid-November in a rubbish dump off Redwine Road in the suburb of East Point, a jurisdiction outside of Atlanta’s city limits, and many miles from the bicycle and Milton’s home. His death was not at first considered a homicide since there were no marks of violence on the skeletal remains.

The Atlanta Child Murders and Wayne Williams

A few weeks before Milton’s remains were found, Yusef Bell, an extremely gifted nine-year-old disappeared on his way to the store to buy snuff for a neighbor. After buying the snuff, a woman thought she saw him get into a blue car with a man she believed was the former husband of Yusef’s mother Camille. The police later discounted this sighting.

Unlike the earlier three cases, Yusef’s disappearance received some media attention as Camille begged the abductor to release her boy. Her community was rallying around her for emotional support.

Camille’s hopes vanished when a school custodian in the abandoned E.P. Johnson Elementary School discovered Yusef on November 8. His body had been wedged into a concrete hole in the floor. He had been strangled to death, either by hand or ligature. The boy had been barefoot when he disappeared and was still barefoot when he was found, but the bottoms of his feet had been washed clean.

This case had finally captured the attention of the community at large. Yusef’s funeral was a major event. City officials, black leaders and politicians of every color fell all over themselves to give their condolences to Camille and mourn the tragic death of this promising young man. Mayor Jackson promised a full investigation but none of the four murders were considered connected — just random acts of violence that “happen” in poor black neighborhoods.

Camille Bell and her friends didn’t buy that story and realized that these murders were not typical. They continued to articulate their displeasure at the efforts of the police and the city administration, which they considered too distant from its black constituency. Along with this vocal displeasure crept in the fear that the murders were racially motivated and that the Klan was behind it.

The police got some breathing room between the last half of November and early March. In March of 1980, the killing of black children and youths began again in earnest.

article continued below

article continued below

Killing in Earnest

The lull came to a nasty end on March 4, 1980 when twelve-year-old Angel Lenair finished her homework and left her apartment in southwest Atlanta. When she didn’t come home for her favorite television show, her mother Venus Taylor called the police.

Venus Taylor’s worst fears were confirmed on March 10, 1980 when the police found Angel’s body tied to a tree with an electrical cord around her neck and a pair of panties, that did not belong to Angel, stuffed in to her mouth. Cause of death was asphyxiation by strangulation with the electrical cord. Although Angel’s hymen had been broken and there were some minor abrasions in the genital area, the medical examiner did not interpret those facts to mean evidence of sexual assault. Those findings became controversial and did not mean that Angel was not the victim of some sexual abuse.

This particular case was quite different than the previous cases, in that the victim was female and her body was found under different circumstances than the previous male victims. There were two suspects, who were eventually cleared of the murder.

The very next day after Angel’s body was found, Jefferey Mathis, aged ten, had left his home to buy cigarettes for his mother in the early evening. Like Yusef Bell, Jefferey would never return from his errand, which was only a few blocks away from his home. His mother Willie Mae Mathis became worried when he was gone over an hour and sent her other sons to look for him. Later that night, a patrolman told Mrs. Mathis to call the missing person’s department if he did not come home by morning.

What she did not immediately understand when she contacted that department the next day is that the missing person’s department at that time in the Atlanta Police Department — and in many major cities — did very little to investigate the disappearance of young people. It was assumed that children and teenagers were runaways and not the victims of foul play.

Filed Away and Forgotten

Jefferey had last been seen by a friend getting into the backseat of a blue car, possibly a Buick. Thirteen days after Mathis had gone missing, Willie Turner, who had recognized Mathis’ picture from the newspaper, claimed that he saw Jefferey in a blue NOVA car, driven by a white adult man. Willie Turner also told police that the man he had seen with Mathis had later in the week pulled a gun on him before taking off in his car.

Police did little in response to the information given by Turner. The report was filed away and forgotten. The blue car that was earlier seen by Mathis’ friend in connection with Jefferey’s disappearance was very similar to the description of a car seen by an eyewitness in a later disappearance case of a boy named Aaron Wyche. Jefferey Mathis’ two brothers had also reported seeing a blue Buick in the driveway of a house that Jefferey frequented. Interestingly, shortly after Mathis’ disappearance, boys from his school had complained to their principle that two black men in a blue car had attempted to lure them away from the schoolyard. The youngsters had memorized the license plate and reported it to police. Once again, police did little to investigate.

Eric Middlebrooks, 14, got a phone call around 10:30 P.M Sunday night, May 18, 1980. He immediately grabbed his tools and told his foster mother he was going out to repair his bike. Early the next morning, his body was found a few blocks away. His bicycle was nearby. Eric had been bludgeoned to death.

As police looked into this murder, it was suspected that Eric had been eyewitness to a robbery and that the robbery suspects were also the murder suspects. However, there was insufficient proof.

Just outside the city limits of Atlanta in the Decatur, twelve-year-old Christopher Richardson lived in a nice middle class neighborhood with his grandparents and mother. In the early afternoon of June 9, 1980, Christopher went to a local recreation center to swim. He never got there.

Wayne Williams

A few weeks later in the early morning hours of June 22, 1980, an amazing crime occurred. Seven-year-old LaTonya Wilson was abducted from her home. A neighbor claimed that she saw a black man remove the windowpane in the Wilson apartment, climb into the apartment and leave with the little girl in his arms. Chet Dettlinger in his book The List describes how difficult it would have been to do what the neighbor claimed she saw:

“If , as the neighbor said, the kidnapper climbed through that window, he stepped squarely onto a bed where two other Wilson children were asleep. Neither woke up. Once inside, he stole LaTonya from her bed, carrying her past the door of her parents’ room. He walked out the back door, leaving it ajar. Outside, he is said to have paused in the parking lot to speak to another black male, all the while holding the limp figure of LaTonya Wilson under his right arm.”

Whoever was responsible for these murders and disappearances was approaching a record in the history of crime. What the citizens of Atlanta, the city government, and eventually the FBI, didn’t realize was that it was just the beginning. What Bernard Headley aptly named “A Summer of Death” was just beginning.

The Atlanta Child Murders

The cumulative ineffectiveness of the Atlanta police to solve the growing number of missing and murdered children galvanized three of the victims’ mothers — Camille Bell, Willie Mae Mathis and Venus Taylor — to join with Reverend Earl Carroll to form the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP). The group pressured both the Atlanta city government and sought support from the white corporate power structure.

The group was formed none too soon because the day after La Tonya Wilson’s shocking abduction, ten-year-old Aaron Wyche disappeared. The next day his body was found beneath a six-lane highway bridge that passed over railroad tracks in DeKalb County. His death was caused by asphyxia, said the medical examiner, because he landed in a way that prevented him from breathing. This death was not initially considered a homicide even though Aaron was deathly afraid of heights and would not have voluntarily climbed that trestle unless he was running away from someone. The assumption was that Aaron fell off the bridge, despite the fact that the guardrails on the bridge were almost as high as Aaron was. Dettlinger says, “There is no way Aaron Wyche could have fallen off that bridge. Jumped or been thrown, maybe; but fall off, no way.”

July 6, 1980, nine-year-old Anthony Carter was out playing hide and seek with his cousin after 1 A.M. in the morning when he vanished. He was found stabbed to death the next day behind a warehouse less than a mile from his home.

An Epidemic of Murder

Throughout this epidemic of murder and missing children, the Atlanta police maintained that the cases were separate and not connected. The general attitude was that Atlanta in recent history had a high rate of murdered children. However, after the publicity that the mothers’ group STOP was getting, the city government bowed to the political pressure and announced the formation of a task force in mid-July to focus their investigative efforts.

Two weeks later on July 30, 1980, eleven-year-old Earl Terrell went with some friends to the South Bend Park swimming pool. Earl began to misbehave and the lifeguard threw him out of the pool. After that, Earl disappeared.

Earl’s aunt, who lived next door, got a phone call. “I’ve got Earl. Don’t’ call the police,” he told her. Shortly afterwards, the man — who sounded like a white southerner — called back, saying, “I’ve got Earl. He’s in Alabama. It will cost you $200 to get him back. I will call back on Friday.” (Detlinger and Prugh).

According to Detlinger, police learned of a child pornography ring that was operating right across the street from the South Bend Park pool. John David Wilcoxen was convicted when police found thousands of photos of children pornographically displayed. Police dismissed the connection between Wilcoxen and Terrell because the photos were of white boys, but a witness claimed that Earl Terrell had been to Wilcoxen’s house several times. Also, there was some disagreement as to whether the photos were actually all white boys or not.

At this point, LaTonya Wilson had been abducted and Earl Terrell potentially abducted and transported across state lines. Kidnapping and transporting a person across state lines was the jurisdiction of the FBI. Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson had been trying to get the FBI into this case and now he had the proper rationale.

The summer ended up with the death of one more child. Thirteen-year-old Clifford Jones had come to visit his grandmother in Atlanta and was found strangled by some unknown ligature on August 20. His body had been put in a dumpster wearing shorts and underwear that were not his.

Police were presented with a strong suspect in a manager of a laundromat that, according to Chet Detlinger, “was widely known for homosexual gatherings.” Bernard Headley sums up the case against this suspect: “Three youthful witnesses saw the manager go into the rear room with a black boy. One of them said he saw the manager ‘strangle and beat’ the boy, then carry his body out to the trash container…Two polygraph tests were administered to the laundromat manager. He ‘failed’ both, according to FBI records — even though he admitted that he knew Clifford and that Clifford was in his laundromat on the evening of August 20, 1980. Medical experts had determined that the time of Clifford’s death was between four and six hours before the discovery of his body, which would have placed the laundromat manager with the boy around the time he was killed. The authorities had not charged the man with anything, however, because they determined that the youth who said he actually saw Clifford Jones being murdered was ‘retarded.'”

Another witness said he had seen the man, whom he knew, carry a large object wrapped in plastic and place it by the dumpsters the night before Jones’ body was discovered. The large object wrapped in plastic turned out to be the body of Clifford Jones. Two other witnesses claimed to see the same man, who they had also known, carrying an object wrapped in plastic to the dumpsters.

The List

Once the official task force was formed, the police had to decide which cases to include in their investigation. Those specially assigned cases, which represented murders that fit particular parameters, were compiled into a list. The “List” took on a life of its own during the media hype and investigation into the murders and is still the source of controversy. Unfortunately, The List led to more people misunderstanding the facts about the cases than to their understanding of them. This was largely due to the inaccurate and incomplete information gathered about each of the victims, which were often times caused by negligence, ignorance and mismanagement by authorities.

In many instances reports conflicted with one another; bodies were misidentified; reports were sometimes changed or lost; and crime scenes destroyed. Moreover, according to author and investigator Chet Detlinger, many that should have made the List never did. Of the many hundreds of murders that occurred during the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, at least ninety of those shared a similar geographic and/or social connection with one another. Connections that would later be ignored by officials in more than sixty of the ninety cases, during the course of the investigation into the murders. The Task Force Unit ignored the more than sixty cases mostly because they failed to meet the parameters that police were continuously changing and because they failed to notice the geographic and social connection between the victims, both on and off The List.

More than sixty names never made the List, which could have been because they fit similar social and geographical patterns of those cases that had qualified for the List. Unfortunately, the Task Force disregarded many as “special cases” because they failed to meet their parameters, which were continually modified. Some, who had failed to make the List at one point, could have qualified for it at another, after the List was changed. This allowed many victims cases to slip through the cracks that should have received the attention they deserved. After Wayne Williams arrest, more than twenty people were murdered, some of which could have also made The List. They never did because police had stopped adding names to the List after they had Williams in custody. Some of those who had fit the social and geographic parameters recognized by Dettlinger were Cynthia Montgomery, Angela Bacon, Joseph Lee, Faye Yearby and Stanley Murray. They are just a few of the many who had not made the List.

For example, Faye Yearby, twenty-two years old, was considered too old to have made the List at the time of her death in January of 1981. She was found almost nine months after Angel Lenair ‘s body had been found, stabbed to death and tied to a tree. Yearby had also been found bound to a tree in almost the exact same position Angel had been found. Even though her death, in many ways, resembled that of Angel Lenair, Task Force Agents refused to acknowledge any link between the cases. Furthermore, she was never added to the List because of her age and her sex.

On September 14, 1980, ten-year-old Darron Glass vanished. Shortly afterwards, his foster mother received an emergency phone call from someone claiming to be Darron, but when she answered the phone, the line was dead. The police ignored the case however, because Darron had run away several times before.

The black leadership, churches and community at large were mobilizing along a number of fronts to deal with this crisis. Activities ranged from prayer vigils, safety education programs, and even regular searches for the missing children. The Atlanta government had even gone so far as to bring in psychic Dorothy Allison, who had assisted in some high-profile cases.

article continued below

WickedWe Recommends:

article continued below

A Geographic Connection

Chet Detlinger was the first to understand that there was a geographic connection to the victims. A number of the victims knew each other and either lived, were last seen or their bodies were found in several key areas of the city. Detlinger tried valiantly to explain the unfolding pattern that he saw emerging, so that police could concentrate their efforts in these critical areas, but police did not warm to his theories.

What the police were still wrestling with was a case in which there were many different causes of deaths, modus operandi, and signatures, only a few of which seemed to fit a pattern. Usually a serial killer selects a particular type of target that is either male or female, rarely both. While the MO can change based upon the killer’s experience or opportunity, the signature, according to Robert D. Keppel (Signature Killers), is the killer’s “psychological ‘calling card’ that he leaves at each crime scene across a spectrum of several murders. “For example, when the killer in one murder intentionally leaves the victim in a position so the victim will be found open and displayed, posed physically spread-eagled and vulnerable; or when he savagely beats that victim to a point of overkill and violently rapes her with an iron rod…” Part of the problem was the List itself. It was very unlikely that one individual or group of individuals was responsible for all of the murders and disappearances. Comparing the abduction of LaTonya Wilson with the stabbing death of Clifford Jones suggests very different perpetrators. However, at least in some of the cases, it appeared that at least one or possibly several unconnected serial killers were at work. As the murders and disappearances continued relentlessly, various patterns did emerge.

No End in Sight

Late in the evening of October 9, 1980, twelve-year-old Charles Stephens had gone missing. He was found murdered the next morning on a hillside. Stephens had died from suffocation from an unknown object. At the crime scene, the evidence had been contaminated by a police officer when he threw a blanket over the corpse of the boy. The fibers from the blanket were mixed with the fibers already at the scene. The fibers found were thought to have come from the red interior of a Ford LTD.

A drug dealer went to police a day after Stephen’s body was discovered. He told police that on the same day Charles Stephens disappeared, he had gotten into the car of a client of his to sell drugs. When the drug dealer looked into the back seat of the car he saw a young boy lying lifeless with his head turned towards the trunk and wrapped in a sheet. When the drug dealer asked about the boy, the driver of the car became angry and told him the boy was merely doped up and passed out. The drug dealer stated to police that he was concerned about the boy because he didn’t look doped up but worse off, possibly dead. The driver of the car told the dealer to forget what he saw. He later threatened the dealer with his life if he had said anything about the boy in the backseat. It was then that the dealer went to police and told them the story. He added that he knew the man to be a pedophile and had on occasions been offered money to find the driver young boys with whom he could have sex.

In mid-October, the skeletal remains of LaTonya Wilson were found in northwest Atlanta, not too far from her home. It was impossible to determine cause of death or whether she had been sexually abused given the state of her body’s decomposition.

Citywide Curfew

During the fall of 1980, the mayor of Atlanta issued a citywide curfew. It was feared that the killer(s) would strike during Halloween, possibly targeting trick-or-treaters as they walked the city streets. The city patrols were stepped up in an effort to prevent another murder. Unfortunately, all attempts failed when yet another body had been discovered in the first week of November.

Nine-year-old Aaron Jackson, a friend of earlier victim Aaron Wyche, was found dead beneath a bridge in the South River in November 1980, close to where Wyche’s body had been discovered. Jackson’s cause of death was documented as, “probable asphyxia.” Like Charles Stephens, it was believed that Aaron Jackson had been smothered.

At about the time Jackson was thought to have been killed, a woman had witnessed a man at the scene where the body was later discovered. The woman reported what she had seen to the Task Force who, in turn, failed to respond to the report. However, that was not the only error made by police concerning this case. Throughout the investigation, details would be consistently confused with the details concerning Jackson’s friend’s case, Aaron Wyche. It seemed that the cause of the confusion stemmed from the fact that the boys were very good friends and shared the same first names.

Aaron Jackson was later connected with “Pat Man” Rogers, with whom he and Wyche were friends and neighbors. At one time, “Pat Man” had a crush on Jackson’s sister. Patrick “Pat Man” Rogers was the next to go missing.

Sixteen-year-old Patrick “Pat Man” Rogers was a karate fanatic and singer. He was often spotted at Bruce Lee movies or singing with his friend Junior Harper. He had known many people within his neighborhood. He was also connected to at least seventeen murdered victims, both on and off the List.

Rogers had disappeared on November 10, 1980. He, like other victims including Darron Glass, was thought to have run away. Therefore he was not added to the List for quite some time. A week before his disappearance, he had told his mother that he had feared that the killer was close. His friend’s mother told police that Rogers was looking for her son to tell him that he had found someone to manage their singing careers – a man named Wayne Williams. Rogers was found on December 21, 1980, face down in the Chattahoochee River. He died from a blow to his head.

Wayne Williams

Dettlinger and Prugh stated in The List, that after the death of Jackson, “no more preteen ‘little boys’ were added to the List. The geography changed, too.” Furthermore, the murders seemed to move away from the center of the city to the outlying suburbs.

Lubie Geter disappeared in January of 1981. He was fourteen-years-old. Even though he fit all the parameters required by the authorities at the time to make the List, it took two days before the police began their investigation of the crime scene after Geter’s body had been found in February of 1981. The body of Geter was extremely decomposed when happened upon by a man walking his dog through the woods. When he was found, he was only wearing his underwear. The medical examiner believed that Lubie died from asphyxiation from manual strangulation.

Geter had been connected with two white male pedophiles — the child molester connected with earlier victim, Earl Lee Terrell and another unidentified man, who would be later connected to List victim William Barrett. An acquaintance of Geter had seen him with the molester linked with Terrell on several occasions. The convicted child molester that had been linked with Terrell was also never a suspect in the murder case of Geter.

Terry Pue was fifteen when he had disappeared in January of 1981. He had been last seen at a hamburger restaurant on Memorial Drive and was a friend of List victim Lubie Geter who had gone missing the same month. An anonymous white caller had phoned the police and informed them where they could find the boy’s body. Pue was found near interstate 20 on Sigman Road, in Atlanta. He had been strangled by some sort of ligature. The same caller had also indicated that the remains of another victim could be found on the same road. Years later, those remains were finally located but never identified. Some suggested they were the remains of still missing Darron Glass. The unidentified remains were never added to the List, even though Pue’s were.

And Yet Another

Patrick Baltazar was eleven when he had disappeared on February 6, 1981. A man cleaning up the grounds one week after he had gone missing found Baltazar’s body in an office park. The boy had been strangled to death and the rope thought to have been the murder weapon, lay close to the body. Before his death, the Task Force had received a call from the boy; saying that he believed the killer was coming after him. Unfortunately, the Task Force failed to respond. One wonders if Baltazar would still be alive today if they had responded. After Baltazar had gone missing, his teacher had claimed she had received a phone call from a boy she thought to be Baltazar. The boy never said who he was, he merely cried into the receiver of the phone.

That same month, thirteen-year-old Curtis Walker disappeared and was immediately added to the List. Curtis had lived with his mother and uncle at the Bowen Homes housing project in Atlanta. Both he and his uncle, Stanley Murray, would be murdered. Curtis would make the now infamous List, but his uncle would not. His body was found on March 6, 1981 in the South River. His death, like many of the other List victims, would be documented as caused by asphyxia, probably strangulation with a cord or narrow rope.

That same day, FBI agents found the remains of Jefferey Mathis, missing almost a year. His funeral was captured on national news.

Joseph (Jo-Jo) Bell was fifteen when he disappeared on March 2, 1981. Two days after he had gone missing a co-worker of his, who worked at a popular seafood restaurant named Cap’n Peg’s, told his manager that Jo-Jo had called him and told him he was, “almost dead.” The boy said Jo-Jo had pleaded for his co-worker to help him, before hanging up the phone. The manager reported the call to police. Several days later, Jo-Jo’s mother received a call from a woman who said she had Jo-Jo. The same woman had called back and spoke with Mrs. Bell’s two other children. Mrs. Bell immediately called the Task Force, who never contacted her back. Frustrated, she contacted the F.B.I., but it was too late. Jo-Jo was found on April 19, 1981 in the South River. His cause of death was “probable asphyxia.”

Jo-Jo was linked to several victims on and off the List. His mother had befriended a fellow inmate while serving time for murdering her husband. That woman happened to be the sister of Alfred Evans. Jo-Jo had gone to summer camp with Cynthia Montgomery, a murdered victim who had not made the List, but could be connected to many victims who had made the List. Jo-Jo was also good friends with Timothy Hill, a very troubled young man with violent tendencies, who disappeared eleven days after Jo-Jo. He and Timothy Hill were known to frequent a house on Gray Street known as Uncle Tom’s. A sixty-three year-old homosexual man named Thomas Terrell, who was known to have a particular interest in young boys, owned the house.

Timothy Hill, Jo-Jo’s friend, disappeared that same month. Tom Terrell’s next-door neighbor saw Timothy the day before he disappeared on March 12, 1981. A young man who had also known Timothy and Tom told police that the two frequently engaged in sex together. Tom would usually pay thirteen-year-old Timothy for sexual favors. Terrell himself admitted to police that he had engaged in sexual acts with the boy. Another witness reported to police that Timothy spent the night at Terrell’s after missing his bus the day before he was reported missing. That same witness was the last to see Timothy. He claimed that the night before he disappeared, he saw from his window Timothy talking with a teenage girl.

Timothy was found on March 30, 1981 in the Chattahoochee River. He was the last child victim to be added to the List. His cause of death was also listed as asphyxia. Terrell was never suspected in the disappearance or murder of Timothy or Jo-Jo. Timothy was later linked with Alfred Evans, Jefferey Mathis, Patrick Baltazar and Anthony Carter.

Throughout the horrible series of murders, the children began to get older. Also, rivers fast became the favored dumping ground for victims. Suddenly, there were no more child victims. Were the safety education programs and curfew finally working? Or had the murderer’s taste simply matured?

No More Children

That same year, residents of a housing project named Techwood Homes took to the streets in protest that the police were not doing their jobs in protecting the public. The group of residents decided to take matters into their own hands and they formed a “bat patrol.” The patrol was made up of residents armed with baseball bats, hoping to prevent murders from happening in their community. Sadly, the resident’s attempts, like the authorities, had also failed to prevent the murders from occurring. On the exact day that the residents had taken up “bat patrol” and in the very housing project in which it was formed, another person named Eddie (Bubba) Duncan disappeared.

The first adult to make the List was twenty-one-year old Eddie (Bubba) Duncan. He disappeared on March 20, 1981 and was found dead on April 8, 1981. He, like Timothy Hill, had been dumped in the Chattahoochee River. Eddie had several physical and intellectual handicaps. With Duncan’s death, the parameters of the List changed to encompass older victims. Before this period, other victims who were young adults were left off the List because they were considered “too old.” Those earlier young adult victims were never added, even after the parameters changed. Once again the medical examiner guessed; “probable asphyxia” was documented. And, Eddie Duncan was also connected with another list victim, “Pat Man” Rogers.

Immense sums of money were offered as rewards to help find the killer(s) at large. Much of the money was donated or raised by corporations and famous figures, such as Muhammad Ali, Burt Reynolds and Gladys Knight and the Pips. In 1981, President Reagan issued more than two million dollars to the city of Atlanta and the Task Force to use towards the investigation and for citizens who needed help in dealing with the stress of the murders. Other monies that were donated and raised were mostly used to help in the investigation, as well as to help the families of the List victims. Unfortunately, only a few of the victim’s families ever received the money that was raised or donated. The city and nonprofit organizations poorly controlled the money. Much of the money fell through the cracks of the system, misplaced or lost all together. However, despite the massive flow of money into the city to help put an end to the murders, they still continued.

Wayne Williams and the Atlanta Child Murders

The second adult to make the infamous List was twenty-year-old Larry Rogers (no relation to Patrick Rogers). He turned up dead after missing for more than two weeks in April 1981. He was not found in a river, like the three victims before him, but in an abandoned apartment. His cause of death was documented as “probable asphyxia, by strangulation.” Rogers was mentally retarded.

Rogers was one of the few victims to be connected to Wayne Williams. Supposedly, Williams had hidden the younger brother of Larry Rogers, from police. The younger Rogers had been involved in a violent fight in which he suffered a head injury. It was Wayne Williams, in fact that had taken him to the hospital. Williams overheard on his police scanner news of the fight and had beaten the police to the scene. Williams had picked up the mother of the boys and took her to his apartment where young Rogers was. Mrs. Rogers would later testify against Williams at his trial. The apartment that Williams had taken her to was close by to the place where her older son was later found dead.

Twenty-three year old ex-convict, Michael McIntosh was last seen on March 25, 1981, by a shop owner who said that the young man had been beaten up. The store owner had said McIntosh told him two black men had roughed him up. He was never seen alive again. McIntosh had lived across the street from Cap’n Peg’s Seafood Restaurant, where Jo-Jo had worked. He had, in fact, known Jo-Jo Bell. Like Jo-Jo, McIntosh had been known to hang around with homosexuals and it was believed he was one himself. He had been seen several times at Tom Terrell’s house, a house that both Jo-Jo Bell and Timothy Hill had often frequented.

McIntosh was pulled from the Chattahoochee River, in April 1981. He too had died from “probable asphyxia,” according to the medical examiner. McIntosh had known another List victim named Nathaniel Cater, who would disappear a month later.

John Porter, like McIntosh, was an ex-convict. He spent much of his time with his grandmother whom he lived with on and off. She had kicked him out of the house on several occasions because of his strange behavior. He had been suffering from severe mental problems and had spent a length of time in a mental hospital. He was kicked out shortly before he had disappeared because his grandmother had found him fondling a 2-year-old-boy she was caring for, in her home. He was twenty-eight when he was found dead in April 1981. He had been stabbed six times and left on a sidewalk in an empty lot. Porter originally did not make the List, until the Wayne Williams trial when he and Williams were linked through fiber matches.

Twenty-one-year-old Jimmy Ray Payne had also disappeared the same month as Porter. Police reports stated that his sister last saw Payne the day before his disappearance. He had shared an apartment with his sister and mother. His sister told police that he was on his way to sell old coins at a coin shop. However, Payne’s girlfriend had claimed to see him the very day he had supposedly disappeared. She told to jurors that he had walked her to the bus stop the morning of April 22. She had become worried when he did not pick her up from the bus stop, as they had planned to meet there. Payne had been known to suffer bouts of depression, especially during his incarceration while serving a sentence for burglary. Payne, at one time, had attempted to hang himself with his bed sheets, yet failed to succeed when a social worker found him. He had survived that one brush of death, but would not live for long afterwards. Payne was found a week after his disappearance floating in the Chattahoochee River. His cause of death was reported as “undetermined,” according to the county medical examiner. It was believed that he had been in the water almost the entire length of time he had been missing.

William Barrett (Billy Star) was a seventeen-year-old juvenile delinquent when he had vanished in May of 1981. He vanished on his way to pay a bill for his mother. The following day, his body was found close to his home. He had been both strangled and stabbed. The medical examiner reported that the stabbing occurred after Billy died from strangulation.

Earlier police reports stated that threats by a “hit man” had been made against Barrett. Barrett had also been connected to a white man previously convicted of pedophilia. The same man was also said to have known List victim Lubie (Chuck) Geter. A witness had seen Geter on several occasions at the suspect’s apartment. The same man had also been witnessed at Barrett’s funeral.

Ex-convict Nathaniel Cater was twenty-seven years old when he became the last victim to make the List. He had lived in the same apartment building as LaTonya Wilson. It is unknown as to exactly when Cater had disappeared. What authorities did know was that he was an admitted homosexual prostitute, drug dealer and alcoholic. A witness, who had known the suspect in the death of Clifford Jones, said Cater had admitted to selling himself, his blood at the blood bank and dope, in exchange for money.

Dettlinger and His Map

Dettlinger, an ex-police officer, public safety commissioner and consultant for the U.S. Justice Department, led a voluntary investigation into the Atlanta murders beginning from 1980 and continuing until Wayne Williams‘ incarceration. Dettlinger volunteered his services first to the police who refused him and later to the mothers who accepted his help to try and put an end to the murders. Dettlinger teamed up with Dick Arena, an ex-crime analyst, and private investigators Bill Taylor and Mike Edwards, along with the help of other volunteers, to assist in the investigation. Dettlinger and his group of volunteers completed much of the “leg work” the police didn’t do, including going door-to-door in the neighborhoods where victims lived and disappeared, asking questions and seeking leads and connections into the murders. What Dettlinger discovered was a definite pattern including all of the victims on the List and many victims who never made the List.

Dettlinger’s findings were significant in that they recognized a social and geographic pattern between the victims. During the peak of the Atlanta murders, he was able to predict with a degree of accuracy where victims would disappear and be found. Task Force Agents and police, who refused to acknowledge any connections among the cases, either geographic or social, at one point suspected Dettlinger in the murders. However, he was quickly released when authorities realized the information and knowledge Dettlinger had and which they lacked came from their own incompetence, mis-assimilation of information and mismanagement with the handling of the investigation. The FBI later used Dettlinger as an expert consultant, realizing that he knew more vital facts concerning the investigation than the police department.

Dettlinger first began his map of murder victims in the summer of 1980 who had initially made the List. However, he quickly discovered that there were many that police had left off that were worth examination. Dettlinger’s list of victims had well outnumbered the Task Force’s list. Several of those victims who had been first ignored by Task Force Agents, such as Aaron Wyche and Patrick Rogers had made Dettlinger’s list soon after their disappearance. Some of those names were later added by Task Force Agents due to increasing pressure by Dettlinger, who was able to provide them with information they lacked that allowed them to later connect the cases.

Dettlinger mapped out the precise location of where the victims had lived, where they had disappeared and where they had been found. By doing this he discovered that the victims were connected to Memorial Drive and eleven other major streets centered in that immediate area. Dettlinger had also recognized that the murders moved in an eastward direction.

After Patrick Rogers’ death, the victims that were found were older and their bodies were disposed of further outside the city limits. However, Dettlinger and Prugh are quoted in their book, The List as saying, “The streets didn’t change…but it was necessary only to extend the streets on the map, not add new ones. Even those Chattahoochee and South River findings would occur at bridges carrying one of the streets on the map…” Therefore, the parameters basically remained the same despite the ages of the victims.

The Splash from the Bridge

“It” happened in the early morning hours of Friday, May 22, 1981 at the James Jackson Parkway Bridge that crossed over the Chattahoochee River where previous bodies had been found. Two police officers were staked out at the bridge in an effort to monitor suspicious activities. Officer Freddie Jacobs was stationed on the Fulton County side or southern part of the bridge. Officer Bob Campbell was stationed beneath the bridge at the northerly Cobb County side of the bridge. Officer Jacobs saw the headlights of a car approaching southbound over the bridge. At about that same time, Officer Campbell heard a car driving over the bridge. Campbell heard a splash in the water. It was the splash that had sent ripples around the world and would mark the beginning of one of the most famous trials in recent times.

According to Officer Jacobs, he had seen a car’s headlights as it was driving over the bridge and was soon after radioed by his colleague Campbell, who had told him that he had heard a loud splash in the water. Jacobs recognized the slow moving vehicle as a white 1970 Chevrolet station wagon. He watched as the vehicle drove over the bridge into Fulton County, where there stood in view a liquor store. He watched as the car turned around and re-crossed the bridge. At the liquor store a veteran Atlanta police officer named Carl Holden was on watch for suspicious activity when he spotted the station wagon. He had followed it as it crossed the bridge into Cobb County.

According to Campbell, he heard a loud splash, unlike the sound that some of the river animals made when they dove in the water, and noticing ripples in the water made from whatever had landed in the river. He saw a car standing on the bridge. Then the car turned its headlights on above the area where he had heard the splash and had seen the ripples. He then radioed FBI Agent Greg Gilliland, who pulled the car over almost a half mile from the bridge. Holden had still been following the car from behind when it was pulled over. The driver of the station wagon was Wayne Williams.

Williams, almost twenty-three-years-old, was a freelance photographer and music promoter who said he was traveling across the bridge to find the home of a potential client with whom he had an appointment several hours later. He told the police the woman’s name was Cheryl Johnson and that he intended to audition her with the possibility of promoting her as a singer. However, agents did not believe his story, particularly when the phone number was incorrect and the address didn’t exist. Williams allowed the authorities to search the car. For over an hour, Williams was questioned about what he was doing on the bridge and his reason for being in the area.

Several hours later, officers dragged the Chattahoochee River around the bridge, but they found no evidence of a body. The next day, police again questioned Williams and began to realize that they were dealing with a most unusual man

Wayne Williams

Wayne Williams, born on May 27, 1958, was the only child of schoolteachers Homer and Faye Williams. The Williams family lived in Dixie Hills, a neighborhood where many of Atlanta’s murder victims had once lived or from where they had disappeared.

His parents doted on him and spent every cent they had supporting his entrepreneurial ventures. From a young age, Williams dreamed of making it big in the broadcasting and entertainment industry. A talented and motivated young man, Williams began his own radio station at the age of sixteen from his parent’s home. He graduated from Fredrick Douglas High School with an honors degree and attended Georgia State University for one year before dropping out. In his late teens he worked for a popular radio station and appeared in [Jet] magazine along with his employer, Benjamin Hooks, an influential black leader at the time who eventually headed the NAACP. Williams spent much of his time marketing his own station and promoting local musical talent, performing odd jobs to fund his ideas and experimenting with electronics, which was his hobby.

Wayne Williams had also sold video footage and photographs of area accidents, such as fires, car accidents and even one plane crash, to local television stations to earn money. He would hear about many of the accidents from his police radio scanner, which allowed him to make it to scenes of accidents sometimes before the police had even arrived.

His dream was to find the next Jackson Five or Stevie Wonder and ride that talent to fame and wealth as their promoter and manager. He spent much of his time talent scouting among black youth and recording the works of the boys he believed had promise. Unfortunately, he did not have the ear to select musicians with enough talent to make it commercially. Nonetheless, he continued to spend his parents into bankruptcy creating expensive demo recordings of boys with mediocre abilities.

Wayne was known around town as a pathological liar and a bullshitter, suggesting that he had major record deals cooking and knew the right people to make it big.

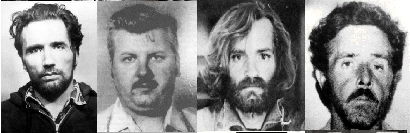

Socially, Wayne Williams lived with his parents and had few friends. Bernard Headley tells of an interesting aspect of Wayne’s life that is typical behavior of serial killers: “He had acquired, for instance, an uncanny ability to impersonate a police officer. The practice got him into trouble back in 1976, when he was arrested in the city (but never convicted) for “impersonating a police officer and unauthorized use of a vehicle.” The vehicle had been illegally equipped with red lights beneath the grille and flashing blue dashboard lights.

There were rumors that he was homosexual, but nothing to substantiate them.

Dettlinger says that in the days immediately following the event on the bridge, Wayne and his father “did a major cleanup job around their house. They carried out boxes and carted them off in the station wagon. They burned negatives and photographic prints in the outdoor grill.”

Building the Case

On May 24, 1981, the nude body of Nathaniel Cater, who had disappeared a few days earlier, was discovered in the Chattahoochee River. The medical examiner had once again documented the cause of death as being “probable asphyxia.” He was unable to establish the time frame in which Cater had expired. Therefore, it was not really known exactly how Cater had died or when, but only that he had stopped breathing for some unknown reason. The medical examiner obliged the police by stating that Cater had been dead just long enough for Wayne Williams to have thrown him off the bridge several days earlier.

Based on the discovery of the body and the “splash” from the bridge, police theorized that Williams had killed Nathaniel Cater and had thrown him off the bridge the night they had pulled him over. Interestingly, four witnesses would later come forward to the police saying that they saw Cater alive after Williams supposedly threw his body from the bridge. This critical information was not shared with Williams’s lawyers.

The authorities monitored Williams’ actions on a continuous basis while they got the necessary search warrants for his home and cars. Throughout the string of murders, a large number of fibers had been found on the various bodies of the victims. The FBI wanted to determine if any of the fibers from Wayne Williams’ environment matched the fibers taken from the murder victims. Also, a few victims had dog hair on them. Samples of the hair from Williams’ dog were taken for comparison.

When the FBI took Williams in for questioning, without a lawyer present, they grilled him about his activities on the night of the bridge incident. Williams told them he played basketball that afternoon at the Ben Hill Recreation Center and then went home. Later in the afternoon, Williams said he got a call from a woman who called herself Cheryl Johnson who wanted to audition for him. She supposedly gave him a phone number and address in Smyrna and arranged to meet Williams at her apartment at 7 A.M. the following morning. He said he stayed at home until he went to the Sans Souci Lounge after midnight to pick up his tape recorder from the manager. He said that he left the Sans Souci when the manager was too busy to see him. Then he told the FBI that he was going to look for Cheryl Johnson’s apartment and drove around Smyrna looking for the Spanish Trace Apartments in which she said she lived. When he couldn’t find the apartments, he said he stopped at a liquor store and called the phone number she gave him, but the number was busy. Later, he stopped again to call her, but that time the phone rang without answer.

Then Williams drove onto the Jackson Parkway bridge and went to a Starvin’ Marvin to call Cheryl Johnson again. This time, Williams claimed, someone did answer but said that it was the wrong number. So then, Williams said he went back toward the bridge when the officers stopped him for questioning.

Some of the problems with Williams’ story were that the Cheryl Johnson part was hard to believe and the claims to have been at the Ben Hill Recreation Center and the Sans Souci before the bridge incident were false. When the authorities checked, they could find no Cheryl Johnson and no Spanish Trace Apartments and the phone number for her was bogus.

The FBI gave Wayne Williams three separate polygraph tests, all of which indicated that Williams was being deceptive in his answers.

Williams surprised everybody when he suddenly called a news conference at his home and handed reporters a lengthy resume — much of which was exaggerated and some of which was false. He told the media that he was innocent and that the authorities were just trying to find a scapegoat. This was the beginning of a huge, continuous media event outside the Williams’ home, which went on for quite some time.

During that time, FBI laboratories claimed that they were coming up with a number of matches between the fibers found on the victims and the fibers from Williams’ home and cars. Also, the labs claimed similarity between the dog hairs on the victims and hair from Williams’ dog.

The FBI was very excited about the fiber and dog hair evidence, but the district attorney of Fulton County, Lewis Slaton, was not so impressed. He did not want to prosecute a case on fiber evidence alone. This was such a major case and fiber evidence could be very confusing and unsatisfying to a jury. He wanted more traditional evidence, such as eyewitnesses, fingerprints, etc. It’s entirely possible that Slaton may not have been thrilled to have the FBI telling him what to do in his own county. It was, after all, Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, who in desperation had brought in the Feds, not Slaton.

Finally Going After Wayne Williams

Several things helped persuade Slaton to finally go after Wayne Williams:

* A number of witnesses materialized who swore they saw Williams with various victims. Hard to say why they had not come forward before, since none of the Task Force documents included a note on Wayne Williams. Williams had not been a suspect until the bridge incident.

* A couple of recording studio people claimed to have seen serious-looking cuts and scratches on Williams’ arms, suggesting the potential of a struggle with the boy victims

* Pressure by Georgia Governor George Busbee to play ball with the Feds.

On June 21, William’s lawyer, Mary Welcome and two county policemen went to Williams’ home with the arrest warrant. Interestingly, Wayne Williams was indicted for the murder of two adults, Jimmy Payne and Nathaniel Cater. However, Georgia law allows that the prosecution can bring into court evidence from other cases if it could be proven that those other cases were part of a “pattern.” That was how Slaton would tie in the murders of the children — an activity that would create controversy for years to come

The Trial of Wayne Williams

Popular black attorney Mary Welcome, a former city solicitor, was the first lawyer on Wayne Williams’ defense team. Initially she chose Tony Axam, an experienced attorney on major cases, to complement her skills. However, Williams fired Axam and Mary replaced him with Alvin Binder, a capable, but abrasive white lawyer from Mississippi.

Judge Clarence Cooper, the first black judge elected to the Fulton County bench, had been an assistant district attorney for a number of years and was a protégé of District Attorney and prosecutor Lewis Slaton. Imaginatively, Fulton County announced that a computer program randomly selected a black judge who just happened to be pals with the prosecution to be the judge on the Wayne Williams trial. Jack Mallard was the most active member of Slaton’s prosecution team.

One very controversial situation was that in the case of Jimmy Payne, the Fulton County medical examiner had written that the cause of death was “undetermined.” That is, it was not determined that Payne was, in fact, murdered. Recognizing the difficulty in prosecuting Williams for a death that was not clearly a homicide, the medical examiner conveniently changed his document to indicate “homicide.” Dettlinger points out that when confronted with the change in the death certificate — which subsequently allowed for Wayne Williams to be indicted in the Jimmy Payne case — the medical examiner said he “checked the wrong box” on the death certificate.” However, there is no box to check on the death certificate, only a place to type in the word “undetermined” or “homicide.”

The trial began on December 28, 1981. The jury was composed of nine women and three men; eight jurors were black and four were white. They were sequestered for the duration of the trial. Opening arguments began in the first week of January 1982.

The defense team was severely handicapped by lack of funds and woefully insufficient time to interview hundreds of prosecution witnesses. They did not have the money to employ the quality of expert witnesses to rebut the vast laboratory findings of the FBI and Georgia crime bureau. Furthermore, the body of forensic evidence on fibers was an order of magnitude greater than what the defense had expected. The cornerstone of the prosecution’s case was the fiber evidence, which was highly technical and carried with it the prestige of the FBI laboratories. To successfully cast doubt on the fiber evidence, expensive, very high caliber expert testimony would have been required. Williams’ defense team simply didn’t have that kind of money.

Also, even though the defense team knew that the prosecution was going to bring in other cases besides the deaths of Cater and Payne, they didn’t know how many and which cases would be introduced. For a defense team short on time and short on money, this was a real problem. Dettlinger, who was on the defense team, states: “During the trial, we didn’t know who the next witness presented by the state would be — or what he or she would be testifying about.”

The “Brady” files is the body of information collected by the police and other forensic experts that points towards the innocence of the accused. By law, the prosecution must turn those Brady files over to the defense before the trial begins. The arbiter of what would be included in the Brady files and when it would be turned over was Judge Clarence Cooper, the D.A.’s former protégé. Not surprisingly, the Brady files were withheld until the last possible minute.

For example, thirty-nine-year-old Jimmy Anthony was a neighbor who had known Nathaniel Cater and claimed to have seen him on the morning of May 23 — the day after Williams was pulled over for supposedly throwing Cater’s body off the bridge. Anthony said Cater told him that he had found a new job. One might suspect that Anthony was mistaken about the time that he had last seen Cater. Yet, three other witnesses, one, who had known Cater well, had also seen him after the bridge incident. Not one of these witnesses would later have a chance to testify in the Williams case. The jury would not be informed of the four witnesses who had seen Nathaniel Cater, as well as many other important suspects and witnesses connected with the case that would have cast doubt on Williams’ guilt.

Regarding the time of death of Nathaniel Cater, the defense brought in its own expert who lost credibility when he announced that Cater had been in the water for at least two weeks. Cater had not even been missing for two weeks. A similar thing happened when the defense’s expert estimated Jimmy Payne’s death.

Atlanta’s Public Safety Commissioner Lee Brown had always maintained throughout the investigation that there was no pattern in the murders. Ironically, it was during Brown’s testimony that Jack Mallard introduced the “pattern” that would allow evidence in ten other cases to be introduced in addition to evidence in the Cater and Payne deaths. The “pattern” became the key enabler for evidence to be used by the state against Williams, especially when linking similar fibers. Furthermore, the Cater and Payne cases standing alone were extremely weak and the introduction of evidence from each of the ten “pattern” cases strengthened their case by providing, among many things, eyewitnesses and most importantly, fiber connections among some of the victims.

The ten “pattern” cases were:

- Alfred Evans

- Eric Middlebrooks

- Charles Stephens

- William Barrett

- Terry Pue

- John Porter

- Lubie Geter

- Joseph Bell

- Patrick Baltazar

- Larry Rogers

The characteristics that formed the “pattern” among the victims were listed by the prosecution as being:

- Black male

- Missing clothing

- No car

- Poor families

- No evidence of forced abduction

- Broken Home

- No apparent motive for disappearance

- Defendant claims no contact

- Asphyxia by strangulation

- No valuables

- Body found near expressway ramp or major artery

- Street hustlers

- Body disposed of in an unusual manner

- Transported before or after death

- Similar fibers

There was a great deal of controversy concerning the prosecution’s “pattern.” Furthermore, if one looked closely into each of the cases, it would be noticeable that several of them did not fit the “pattern” invented by the prosecution. For example, not all of the victims were found near expressway ramps or major arteries, it is unknown whether all the victims were transported before of after they were killed based on lack of evidence and only six of the “pattern” cases showed evidence of strangulation. Therefore, the pattern the prosecution describes is inaccurate. But Judge Cooper, former prosecutor, accepted the “pattern” anyway.

The prosecution focused its efforts on four key areas:

the character and credibility of Wayne Williams,

what happened on the Jackson Parkway bridge,

eyewitnesses to Wayne Williams behavior and alleged interaction with the victims, and

the physical evidence, which was primarily based on fibers, hairs and bloodstains found on victims that matched elements in Wayne Williams environment.

While Wayne Williams did not have a criminal record, his character was not exactly unblemished in the eyes of those who knew him. Most people knew Wayne Williams as a person who either lied about or vastly exaggerated his accomplishments. As an example, Eustis Blakely, a successful black businessman and his wife were friends of Wayne. Wayne told Blakely that he flew fighter jets at Dobbins Air Force base. Blakely knew that was a lie because he had been in the Air Force and was not able to fly planes because he wore glasses. Wayne Williams eyes were much worse than Blakely’s.

But the real showstopper during the trial was what his wife had to say about Wayne. She had asked Williams after he had become a suspect, “If they get enough evidence, will you confess before you get hurt? She said that he answered “yes.” She then went on to say that Wayne told her “he could knock out black street kids in a few minutes by putting his hand on their necks.”

On cross-examination, Binder asked her if she implied that Wayne had killed someone. She answered, “Yes, I do. I really feel that Wayne Williams did kill somebody, and I’m sorry.”

Gino Jordon, who ran the San Souci club, was asked if Wayne Williams had been at his club before the bridge incident, as Williams had told authorities he had been. Jordon said it was not that night of the bridge incident, but the following night that Williams came by the club to pick up his tape recorder. The club cashier confirmed Jordon’s statement.

When the man in charge of the Ben Hill Recreation Center was asked if Wayne Williams was playing basketball the evening of the bridge incident as Williams had claimed, the answer again was no.

These two testimonies reflected that Wayne Williams was lying about what he did before the incident on the bridge. This lack of an alibi played right into the prosecution’s theory that Williams was with Cater that evening and dropped his body off the bridge.

What Williams was left with were a bunch of lies about what he did before the bridge incident and an explanation about what he was doing on the bridge that nobody believed. Attempts to find the mysterious Cheryl Johnson led most people to believe that she was nonexistent.

Then the prosecution presented a group of eyewitnesses who claimed they saw Wayne Williams with various victims or that the eyewitness verified that Cater was alive the afternoon of the bridge incident:

As examples of this eyewitness testimony, Lugene Laster saw Jo-Jo Bell get into a Chevrolet station wagon driven by a man he identified as Wayne Williams. Robert Henry, who knew Cater, saw Cater and Williams holding hands the evening of the bridge incident. A couple of youths claimed Williams made sexual advances to them.

One of the most significant and controversial moments of the trial occurred during arguments and testimony concerning the linkage of similar fibers among the ten “pattern” cases to Cater and Payne’s murder. Investigators found on the bodies of the murdered victims fibers that were similar in appearance to carpet fibers found in Williams home and automobile. In total, there were twenty-eight fiber types linked to nineteen items from the house, bedroom and vehicles of Wayne Williams. Of interest to the prosecution were trilobal fibers, which the state contended, were of a rare variety. Fiber analysts speculated that the fibers found on the victims were most likely transferred to the victims from contact with Williams’s environment, thus connecting him to the murders. The prosecution contended that there were so many fiber matches between the Williams’ household and the victims that it was statistically impossible for the victims not to have been in Williams’ home and cars.

Controversy arose when the state failed to tell the jury that most of the fibers found on the victims were not rare. In fact, such carpet fibers could be found in many apartment building complexes, businesses and residential homes throughout the Atlanta region. Therefore, it would not be that unusual for the victims to have come in contact with trilobal type fibers. There was more controversy over the transference of such fibers. The state argued that fibers were transferred directly from Williams’s environment to the victims. Therefore, one must assume that if fibers could be transferred from Williams’s environment to the victims, then fibers from the victims clothing or living environment would naturally be found on Williams or in his home or car, especially, if they had been killed in his house or transported in his car, which the state believed to have happened. Yet, absolutely no evidence of hair or fibers from the victims was found in Williams’s house or car.

Wayne Williams

Later in the trial, the state informed jurors that five bloodstains had been found in the station wagon driven by Williams. Prosecutors claimed that the blood droplets matched in type and enzyme to the blood of victims William Barrett and John Porter. There was controversy among analysts as to the exact age of the droplets of blood found in the car. If the droplets occurred within an eight-week period, which one analyst believed, then it could have been likely that the blood came from Barrett and Porter who had died within that period. However, another analyst testified that it was virtually impossible to date the stains and if by any chance they had occurred outside of the eight-week frame then it was highly unlikely that the blood came from either victim.

When it came to the issue of motive, in the absence of any definitive evidence of sexual assault of the victims, the prosecution claimed that Wayne Williams hated black youths. Of course, this does not explain the murder of Nathaniel Cater who was 27-years-old — not really a youth — and several years older than Williams. Various people testified to remarks that Williams allegedly made over the years that criticized the behavior of black people and black youngsters in particular.

The defense called quite a number of witnesses. For example, they put the hydrologist on the stand that determined that it was “highly unlikely” that the body of Nathaniel Cater had been thrown off the Parkway bridge, considering where Cater’s body was found. The hydrologist was incensed that the county had pressured his colleague into changing his report to reflect just the opposite.

Also, the defense presented an expert witness who testified that there was no indication that either Cater or Payne had been murdered. One of the two victims had an enlarged heart and could have died of natural causes. Both or either men could have simply drowned. Cater was a known alcoholic and drug taker.

The defense also put on the stand a number of witnesses that either rebutted what prosecution witnesses had said about where Williams was at a particular time or testified that Williams behavior was strictly kosher with the boys who he tried to develop into musicians. Another witness was the police sketch artist who testified that none of the dozens of suspects that she was asked to sketch looked anything like Williams. A college student recruited by Williams for a singing job testified that Williams disliked homosexuals and expected that his client had a high standard of morals.

Williams was put on the stand to defend himself against the charges and some of the eyewitness accounts. Also, he wanted to point out to the jury that he couldn’t have quickly stopped the car on the bridge, opened up the back of the car and hoisted Cater, who was much larger and heavier than Williams, over the shoulder-high guard railings on the side of the bridge.

The goal of William’s testimony was to demonstrate to the jury that he did not have the temperament to commit the murders. However, Jack Mallard repeatedly succeeded in making Williams visibly angry and provoking Williams into verbally insulting the government agents on the case. His show of temper had a big negative impact on the jury.

Williams’ defense team was unable to undo the damage that had been done, both by the state’s case and the poor preparation of their own case. The prosecution had provided the jury with a mountain of evidence compared to what the defense team had. Even though the quality of the evidence presented by the prosecution was doubtful, the sheer quantity of it seemed to overwhelm the jurors. Furthermore, jurors never heard most of the exculpatory evidence from the Brady files that could have changed the outcome of the trial. Prosecutors withheld the files for as long as they legally could, which hardly allowed any time for the defense to prepare a strong case.

In January of 1982, Wayne Bertram Williams was found guilty of the murder of Jimmy Ray Payne and Nathaniel Cater. He is currently serving two life sentences. Consequent to the verdict, the Atlanta police announced that twenty-two of the twenty-nine murders were solved with the presumption that Wayne Williams was responsible.

But that was not the end of the case by any means.

Epilogue

From the time that Wayne Williams was convicted, doubts arose about his guilt. Many black Atlantans felt that the government had manufactured the evidence just to get the case closed. While there are a number of issues in the government’s case that are controversial, the fact is that the prosecutors, especially the FBI, believed that Williams was guilty. Did the government play fair and square during the trial? No, but that does not seem to be unusual, because prosecution is about winning, not about justice or fairness in the abstract.

The facts are that no one ever witnessed Wayne Williams killing or abducting anyone. The most important evidence against him was highly technical fiber evidence that only experts could judge. Any jury presented with the huge amount of fiber evidence in the Williams case and the government’s experts testifying to its veracity would be likely to give it credence.

Unfortunately, Wayne Williams was his own worst enemy. He never came up with a credible reason for being on the Jackson Parkway bridge in the early hours of the morning and his alibis were easily destroyed, but it didn’t mean that he was guilty of murder.

During the appeals process, the Georgia Supreme Court assigned Justice Richard Bell to draft the opinion in the Williams case. Justice Bell, a former prosecutor, wrote that Wayne Williams did not get a fair trial and his murder conviction should have been reversed. When the full court reviewed Bell’s opinion, it was voted down; Bell’s draft was rewritten; Bell was pressured to change his vote, and the majority opinion — to uphold the conviction — came out under Bell’s name in December of 1983.

Justice Bell’s unpublished draft criticized Judge Clarence Cooper for allowing prosecutors to link Williams to the murders of Eric Middlebrooks, John Porter, Alfred Evans, Charles Stephens and Patrick Baltazar. The standards for linking those crimes to the two for which Williams was charged were not met, according to Bell.

Specifically, Justice Bell said, according to Benjamin Weiser, Washington Post writer (Feb. 3, 1985) that “there was no evidence placing Williams with those five victims before their murders, and as in all the murders linked to Williams, there were no eyewitnesses, no confession, no murder weapons and no established motive. Also, the five deaths, while somewhat similar to each other in technique, were unlike the two for which Williams was tried.”

The linking of the other crimes with the deaths of Cater and Payne had the effect of eroding the presumption of innocence. Bell pointed out that “because the evidence of guilt as to the two charged offenses was wholly circumstantial, and because of the prejudicial impact of the five erroneously admitted (uncharged) homicides must have been substantial, we cannot say that it is highly probable that the error did not contribute to the jury’s verdict…”

The other dissenter was Justice George Smith, who did not change his vote as Bell did. Justice Smith stated that admitting the other crimes “illustrates the basic unfairness of this trial and Williams’ unenviable position as a defendant who, charged with two murders, was forced to defend himself as to 12 separate killings.”

In 1985, a five-hour CBS docudrama severely ruffled the feathers of the Atlanta city government. The producer made it clear in the movie that he believes that there were “tremendous breaches of legal ethics” during the investigation and trial and that Williams’ guilt was not proven.

Over the years, an increasing number of people connected with the case do not believe that Wayne Williams is guilty, including some of the relatives of the victims. DeKalb County Sheriff Sidney Dorsey, who as an Atlanta homicide detective first searched Williams home, says, ” Most people who are aware of the child murders believe as I do that Wayne Williams did not commit these crimes.”

In July of 1999, the Augusta Chronicle reported:

“A divided Georgia Supreme Court ruled that a state judge wrongly dismissed two claims raised by Wayne Williams in his bid for a new trial in the slayings of two Atlanta blacks 18 years ago. The 4-3 ruling sends the case back to Judge Hal Craig to rule on Mr. Williams’ claims that prosecutors were guilty of misconduct and that his own attorneys did not effectively represent him at his 1982 trial.”

Williams and his lawyers are seeking DNA tests on the bloodstains found in his cars, which prosecutors claimed were consistent with the blood types of two victims who were stabbed.

Throughout the murder investigation there was a fear in the black community that the Ku Klux Klan was responsible for the murders of the children and young adults. There was also credence given to the theory that the CIA and/or FBI were responsible.

A police informant allegedly claimed that Klan member Charles Sanders tried to recruit him into the racist organization. Sanders allegedly told the man that the Klan was trying to begin a race war by killing black children.