Unwitting Pioneer of the Battered-Woman Defense

Nellie May Madison was sentenced to death for killing her husband, until she revealed abuse

Nellie May Madison got off on the wrong foot in life. She eloped at 13, married several times, chain-smoked, drank whiskey and, she’d later say, shot husband No. 5 in the back because he’d abused her.

Convicted of murder, she was sentenced to death. In 1935, the state Supreme Court upheld the sentence — the first time it had done so against a woman.

Madison’s aloofness earned her such newspaper monikers as “Sphinx Woman” and “Iron Woman.” Unlike other female defendants, she didn’t flirt or cry fetchingly. Supposedly on the advice of her lawyers, she lied on the witness stand, omitting the circumstances of the killing and claiming that the dead man in her apartment was a stranger.

Her conduct alienated nearly everyone.

Nellie May Madison Had Lousy Taste In Men

“They really wanted to nail her,” said Cal Poly San Luis Obispo history lecturer Kathleen A. Cairns. “They didn’t like her lifestyle [nor] the fact that she didn’t break down and cry.”

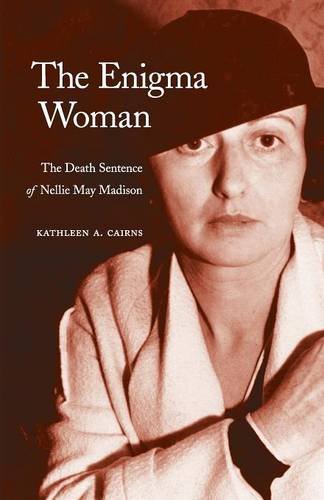

Cairns learned of Madison’s case when she ran across “Newspaperwoman,” the 1949 autobiography of legendary Herald-Express editor Aggie Underwood. Motivated to know more, Cairns wound up writing “The Enigma Woman: The Death Sentence of Nellie May Madison.”

Cairns’ research took her from Madison’s birthplace to her forgotten grave.

“Nellie had been an ambitious, free-spirited young woman, full of optimism for the future,” Cairns said in a recent interview. “She also had lousy taste in men.”

Born Nellie May Mooney

She was born Nellie May Mooney in Red Rock, Mont., in 1895. The youngest child of Irish immigrant ranchers, she was an expert horsewoman and a crack shot, Cairns says.

In 1908, at age 13, she eloped with a man 11 years her senior.

“It was her family’s first serious warning of the reckless and impulsive streak that would cause them, and her, so much anguish and grief,” Cairns wrote.

Nellie’s parents had the marriage annulled and brought her home. She attended business school in Boise, Idaho, where she married twice more.

Nellie and husband No. 3 moved to Los Angeles in 1920. But he walked out, Cairns says, and Nellie divorced him in 1924.

She soon married the brother of her divorce attorney. Husband No. 4, William Brown, was a lawyer too. The couple lived in a middle-class neighborhood and spent weekends at a friend’s ranch in Frazier Park.

Outside The Boundaries

But her multiple marriages — and the fact that she was childless — “placed her outside the boundaries that defined traditional womanhood of her time,” Cairns wrote.

In 1930, she divorced Brown and headed to Palm Springs, working as a hotel manager. There she met a Danish immigrant and coffee shop manager, Eric Madison.

“He had an eye for the ladies, big dreams and schemes, dressed well, and drove a sporty 1930 Buick coupe,” Cairns wrote. In 1933, Eric Madison learned Nellie had a $1,000 family inheritance and proposed.

Nine months later, they were in Burbank, working as cashiers at the Warner Bros. commissary. Eric Madison lasted about two weeks, Cairns says, before he was fired by studio boss Jack Warner for shouting at and shoving director Alfred Green and for overcharging Green by 10 cents for 50 cents’ worth of cigars.

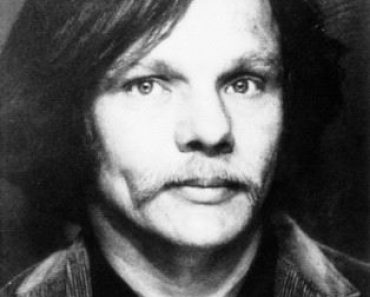

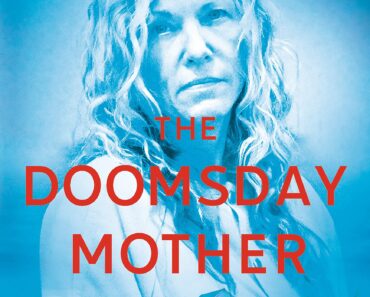

Nellie May Madison

Nellie May Madison

In March 1934, Nellie came home early from a movie to find her husband in bed with a 16-year-old. The girl screamed and fled. Eric Madison beat Nellie and bragged that he had tricked her into a fake marriage for her money. The beatings, Cairns wrote, continued for six days.

Finally, Nellie May Madison bought a gun, intending to scare her husband and retrieve a note he’d forced her to sign that stated they weren’t married.

Just before midnight on March 24, 1934, Cairns says, Eric Madison was in bed, arguing with his wife, who was standing at the foot of the bed. Nellie showed him her gun. Cursing, he reached under the bed for a box of butcher knives and hurled two at her in quick succession. As he turned to reach for another knife, Nellie pumped five bullets into his back.

Other tenants heard the shots but thought they came from the studio, where, Cairns wrote, “Filmmakers were shooting a gangster film, ‘Midnight Alibi’ ” — a Damon Runyon crime comedy.

The next day, a visitor found Eric Madison dead, and his “beautiful, dark-haired widow” — as the newspapers soon called her — was missing. Police found her at the Frazier Park cabin two days later, hiding under a blanket in a closet.

Nellie May Madison and Self Defense

The knives were not logged as evidence, although neighbors claimed to have seen them. Nellie burned the humiliating note, she would later say.

Today, Cairns says, the case clearly would be called self-defense: “Therapists would say she suffered from post-traumatic stress, but no such notion existed in the 1930s.”

Even before Dist. Atty. Buron Fitts knew the circumstances, he vowed to seek the death penalty. “Her motive is of no concern to the prosecution,” a prosecutor assigned to the case declared in a newspaper account Cairns found. “She shot her husband in the back.”

Until then, no woman had been executed in California, although at least two had been condemned: Laura Fair in 1871 and Emma LeDoux in 1906. Fair killed her San Francisco lover and the father of her child when she learned he was married. Her conviction was overturned; she was acquitted at a second trial. LeDoux poisoned her husband, chopped him up with an ax, put the pieces in a trunk and shipped it from Amador County to Stockton. Her death sentence was overturned; she went to prison.

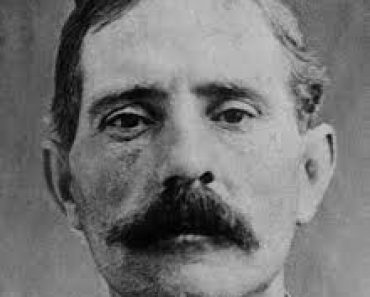

The Hanging Judge and Nellie May Madison

The Hanging Judge and Nellie May Madison

Nellie Madison’s hard luck continued with Judge Charles Fricke, a notorious “hanging judge.” Fricke even left the bench to take the witness stand. Prosecutors summoned him because, during earlier testimony, he had used his stopwatch to count the 3 1/2 -second intervals between shots.

Her defense attorneys, brothers Joseph and Frank Ryan, were reluctant to claim self-defense because of what Cairns called “sordid” details — such as the multiple marriages. Her account of what had happened, Nellie would later say, appalled her lawyers, who urged her to use the bizarre mistaken identity defense. Disbelieving jurors convicted her of first-degree murder.

Nellie stood “defiantly calm” as the verdict was read, Cairns wrote. But ex-husband William Brown jumped to his feet, then sat back down, sobbing loudly.

The Appeals

Sentenced to death, Nellie May Madison appealed. In May 1935, the state Supreme Court upheld the sentence.

Brown urged her to tell the truth about the slaying. The next month, she did — giving the version Cairns describes.

Joseph Ryan voiced outrage at her confession, saying “it was a complete surprise” to him. Nellie fired him and hired former Los Angeles prosecutor and prominent attorney Lloyd Nix.

Then-reporter Aggie Underwood also pleaded Nellie’s case in the press.

Fricke remained unmoved, calling her story “ridiculous.”

But when her version of events became known, a groundswell of opposition to her death sentence arose. Gov. Frank Merriam received hundreds of letters and affidavits demanding that the sentence be commuted. All 12 jurors and two alternates petitioned him. Eric Madison’s previous wife, Georgia, emerged to tell a similar story of abuse. On Sept. 16, 1935, Merriam commuted the sentence to life.

The Campaign of Nellie May Madison

From behind bars, Nellie May Madison waged a letter-writing campaign to get her sentence reduced. On Dec. 31, 1942, Gov. Culbert Olson complied. Exactly nine years after the slaying — March 24, 1943 — Nellie May Madison left prison a free woman.

She moved to San Bernardino and changed her name to Helen Brown. She was married for the sixth time in 1944, to house painter John Wagner, and died of a stroke in 1953 at 58 — still married to Wagner.

“She was born 50 years too soon,” Cairns said. “She was a very complicated woman — an enigma.”

credit murderpedia / Cecilia Rasmussen – Los Angeles Times