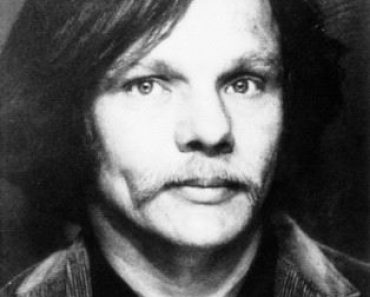

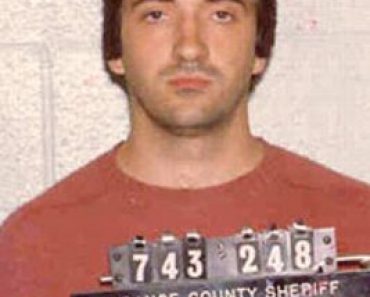

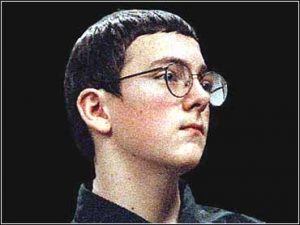

Michael Carneal

Heath High School Shooting

Mass Murder

Crime Spree: December 1, 1997

Michael Carneal stood in the center of the Heath High School corridor in West Paducah, Kentucky. It was December 1, 1997.

His head, normally downward, was this day held high. His back was straight and his hands were confidently wrapped around the handle of a .22-caliber semiautomatic Ruger. All around him, students were running in panic.

For a withdrawn 14-year-old, accustomed to living in fear and cowering from confrontation, it was a dream become reality. Finally, Michael Adam Carneal was finally the one in control.

Just a few feet away, Kelly Carneal barely recognized her little brother. She had never seen him ”look so big.”

Michael Carneal

Until now, each rustle in the tree, knock at the door or shadowy movement in the corner was cause for alarm. And every youngster’s transgression or teen’s teasing was an indefensible assault on his soul.

A siege on Heath High School was to be his chance ”to be more powerful and better than” those who made fun of him.

But the surge of omnipotence lasted precious few moments on December 1st in 1997. After a series of ”pops,” friends and classmates were screaming, five were wounded and three were dead. The respect he’d come looking for had instantly turned to horror.

Michael Carneal dropped his weapon and crumpled. ”Kill me, please,” he said. ”I can’t believe I did that.”

Down the hall, Kelly was sobbing. Her sensitive little brother, who still wanted to be tucked in bed at night, who wept over the plight of street people and winced at the thought of anyone being injured, had just opened fire on their friends.

”None of us could believe that Michael had been involved,” said family friend, Rick Walters. ”He was just your typical kid.”

Michael Carneal Didn’t Fit

To everyone else, maybe. But not to Michael Carneal.

His world, according to a series of interviews Michael and his family have had with police, counselors and investigators, was a place where he didn’t fit in and couldn’t find a friend. A place where he had no control.

Over the years, Michael Carneal had grown so focused on his perceived abuse by classmates and teachers, that he’d begun to see spies in the air vents and assailants in every shadow.

In his mind, and in the stories he wrote for class, he created scenarios where an enemy would attack him or his family and he would battle them to the death, emerging the victorious hero. In one essay, the slain villains were the school ”preppies.”

Heath High School Principal Bill Bond said Michael’s writings were filled with ”pent-up frustration” and hatred.

”He tended to dwell excessively in his world of fantasy to make up for the control and power he felt he lacked in his real life,” said Forensic Psychiatrist Dianne Schetky, who evaluated Michael Carneal for the prosecution following the slayings.

Paranoid Views

”Michael began to perceive the world as a dangerous place where people were out to harm him and his thinking became paranoid. His paranoid views of the world, in turn, reinforced his need to ‘defend’ himself.”

Michael Carneal told Ms. Schetky that his earliest childhood memories were of being left out during preschool play periods and of spending time in first grade with the teacher’s toys ”because I didn’t have any friends.”

In second grade, his only friend was another outcast, Jacob, who was teased because he was poor. And in third and fourth grade, he developed a friendship with Jessica Brown, who rode the bus with Michael and whom he would later kill. Although Jessica once stabbed Michael in the hand with a pencil, Michael said he ”didn’t have any choice except to be nice to her because she was the only person I had to talk to.”

Each year of his childhood, his strongest memory was of some incident of torment. Students putting frog parts on his shoulder during dissection class, someone tossing his prize class project on the roof, classmates hitting him for no reason and a teacher failing him for a creative idea to build jails underwater.

”He hoarded these perceived injustices and dwelt on them rather than letting go of them as many kids would,” Ms. Schetky said in her report.

At Home

Most adolescents turn to peers, athletics, extracurricular activities or academics to help them negotiate the passage of adolescence, lessen their ties to parents and develop a sense of self and autonomy.

But Michael Carneal struck out in baseball, at 5-foot-2 was too small for most other sports and couldn’t compete with his straight-A sister in school. ”He said he’d been trying hard to live up to her, but that he keeps getting into trouble,” Ms. Schetky said.

Developing autonomy at home also didn’t work as it was the only place Michael Carneal truly felt welcome, loved and secure. ”I didn’t think anybody really cared about me except my sister and parents,” Michael said.

Kelly described her brother as ”a baby” at home, who still liked to be cuddled and put to bed at night. His parents, seeing that he lacked the self-confidence of his popular sister, gave him extra attention. His father, John, an attorney, said a special prayer for his son every night.

Michael Carneal was also extremely sensitive by nature and had an unflinching sense of right and wrong. His parents said that even as a child, he ”could never deal with inequities.”

He cried when he saw homeless people and quit the Boy Scouts because he ”disliked the authority thing,” where higher- ranking scouts had more say in activities. He also dropped out of karate after accidentally kicking his partner in the face, causing a nosebleed.

His preoccupation with fair play only made the taunts by classmates more painful.

Michael Carneal Feels Unworthy

”Like many teen-agers, he was hypersensitive to his classmates’ statements about him,” said defense attorney Charles Granner. ”He felt inadequate, unworthy, unloved, un-respected and unaccepted by his peer group.

”At 14 years of age, Michael’s peer group was critical to his self-esteem. Michael felt as if he were a massive failure, doomed to be different and ‘a nobody’ all his life.”

Always, Michael’s response was to shrink back, try harder, be nicer. His sister said Michael wanted desperately to fit in and tried joking around and trying to help others. His efforts, however, were interpreted as signs of weakness by his classmates, whose teasing escalated into name calling and then labeling Michael as ”gay” and a ”fag.”

Michael told investigators that he often would find himself sobbing and not knowing why.

He’d unleash his frustrations on a steel drum kept in the back yard. And, in seventh grade, he contemplated suicide because he ”had no friends for two years.” A year before the slayings, he sliced his arm with a sewing needle when his efforts to befriend a group of classmates backfired and they too began teasing him.

By middle school, he began to see himself as a target for abuse everywhere. In two psychiatric evaluations, Michael Carneal was described as paranoid.

Michael Carneal

When he showered, Michael Carneal covered the bathroom air vents with thick towels because people might be looking. People might climb into the vents through the basement to look. When he’d finish, he would wrap himself in three to four more towels and make a quick dash for his bedroom. Sometimes, he told investigators, when he heard a knock on the window, he thought people were trying to get to him or his family. Often, he would jump up, grab his pocketknife and go check on his mother, Ann, to make sure she was all right.

A month before the slayings, his mother found a stash of kitchen knives under Michael’s mattress. Michael said he was collecting them for protection. If someone came in, maybe he could stop them.

Imaginary Fears

His imaginary fears also kept Michael Carneal from sleeping in his own room. Frequently, he would slip out to the family room couch so that he wouldn’t be so far away from the rest of the family.

That fall, Michael’s grades slumped and he began rocking while sitting at the dinner table. He also started talking to classmates about a movie he’d seen a year earlier, ”The Basketball Diaries,” which featured an academic outcast taking a gun to school and slaying his teacher and classmates, to the applause of his friends.

The idea of using a gun to win respect hit a chord with Michael Carneal. He began telling students that he too was ”planning something big.”

article continued below

WickedWe Recommends:

Rampage

Rampage: The Social Roots of School Shootings

School shootings have decimated communities and terrified parents, teachers, and children in even the most “family friendly” American towns and suburbs.

These tragedies appear to be the spontaneous acts of troubled, disconnected teens, but this important book argues that the roots of violence are deeply entwined in the communities themselves.

Rampage challenges the “loner theory” of school violence, and shows why so many adults and students miss the warning signs that could prevent it.

Drawing on more than 200 interviews with town residents, distinguished sociologist Katherine Newman and her co-authors take the reader inside two of the most notorious school shootings of the 1990s, in Jonesboro, Arkansas, and Paducah, Kentucky.

In a powerful and original analysis, the author demonstrates that the organizational structure of schools “loses” information about troubled kids, and the very closeness of these small rural towns restrained neighbors and friends from communicating what they knew about their problems.

Her conclusions shed light on the ties that bind in small-town America. (Amazon)

The Fantasy of Michael Carneal

Michael fantasized with classmates about pulling guns in school and seeing everyone run away. He and the other boys joked about being able to take over the library, steal the computers and talk on the intercom system.

The other boys laughed about it, but Michael Carneal took it seriously. He began taking his father’s revolver to school, tucked in the bottom of his book bag. ”It made him feel safe,” said Dewey Cornell, director of the University of Virginia Youth Violence Project, who also interviewed Michael.

One day, Michael took a .22-caliber Ruger he’d stolen from neighbors. He pulled it on two classmates but they were unimpressed, saying it wasn’t very powerful. On December 1, he came with an arsenal: two shotguns, two rifles, two handguns.

In the days preceding the slayings, Michael Carneal warned some students who had ”been nice” to him to stay away from an early morning prayer group that met before the start of classes in the front hallway.

The prayer group, according to Mrs. Carneal, was a closed one. One that Michael had never been invited to join.

On Thanksgiving Day, Michael stole the guns he would use to kill his classmates. He climbed in through a neighbor’s window, taking along a duffel bag he had hidden earlier in the woods. He took five guns from their display case and boxes of bullets.

Michael Carneal

After slipping from the house, Michael Carneal climbed the fence, crossed a field and stole into an old barn to examine his cache. Holding them up to the light of the late afternoon sun, he said they made him feel ”powerful.”

Once home, he snuck into his parents’ bedroom, took his dad’s double barrel shotgun, then hid all the weapons in a crate in his bedroom closet.

Two days later, he wrapped the weapons in paper, then a bed sheet. The .22, he put in his book bag.

Monday morning, December 1, 1197, Michael loaded the package into the trunk of his sister’s car, telling her it was props for a play at school.

Once inside the building, he joked with students who asked him if he had guns in his curious package, then made his way to the front lobby.

There, Michael Carneal set the rifles down and put in two bright orange hunting ear plugs. Methodically, he pulled the Ruger from his book bag and the clips from his pocket, positioned himself just to the side of the prayer circle, and began squeezing the trigger.

Michael Carneal Imagined It All Differently

When it was over, Michael Carneal said he’d imagined it all differently. He thought he’d fire one shot, everyone would take off running and he ”could run around and do stuff and take over the school.”

He also expected to return to school the next day, and everyone would be nice to him then. But that is not what happened.

Mentally Ill

Michael Carneal pleaded guilty but mentally ill on October 5, 1998, in McCracken County Circuit Court to three counts of murder and five counts of attempted murder. Carneal told reporters that he could not give a single explanation for his crimes, and that contributing factors included a mistaken belief that his parents did not love him, taunting from classmates, and false claims he was gay. He also stated that he did not know who he was aiming at until he read the names in the paper.

In October 1998, a plea of guilty from Michael Carneal was accepted due to his mental illness. Under a plea arrangement, the judge agreed to accept the pleas on condition that Carneal would receive a life sentence with the possibility of parole in 25 years. (2022). He was given 25 years before the possibility of parole on December 15th 1998. Michael was ineligible for the death penalty because of his age at the time of the crime. According to prosecutor Tim Kaltenbach, the plea allows Michael to receive mental health treatment during imprisonment as long as this is necessary for him or until he is released.

Michael Carneal is eligible for parole on November 25, 2022.

source: murderpedia | wikipedia | wkms.org | mycrimelibrary

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links