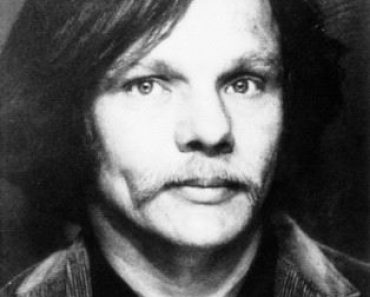

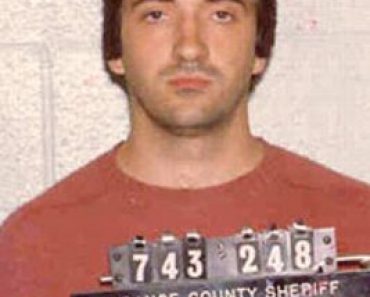

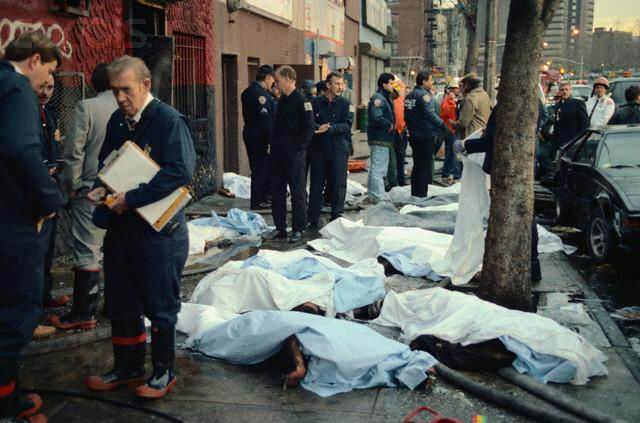

Pic Credit – Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

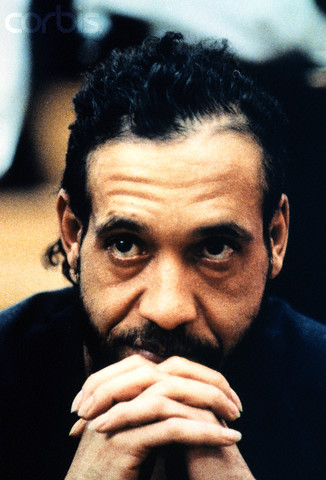

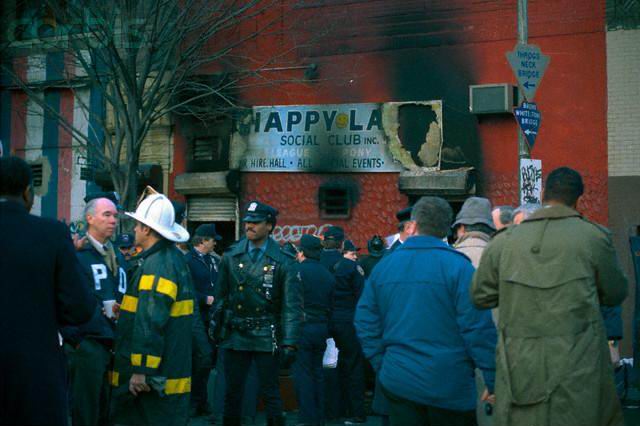

The Happy Land Fire was an arson fire which killed 87 people trapped in an unlicensed social club called “Happy Land” in New York City, on March 25, 1990. Most of the victims were ethnic Hondurans celebrating Carnival. Unemployed Cuban refugee Julio Gonzalez, whose former girlfriend was employed at the club, was arrested shortly after and ultimately convicted of arson and mass murder.

The Prelude

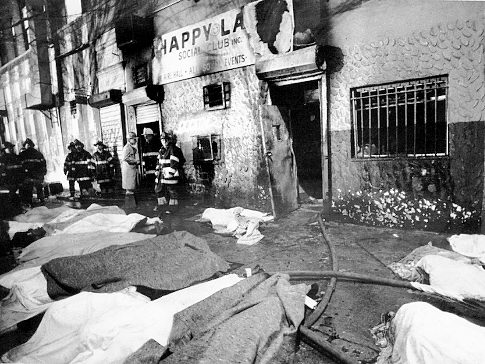

Before the blaze, Happy Land was ordered closed for building code violations in November of 1988. Violations included no fire exits, alarms or sprinkler system. No follow-up by the fire department was ever documented.

On that dreadful evening Julio Gonzalez had a rather heated argued with his former girlfriend, Lydia Feliciano, a coat check girl at the club. Julio was ejected by the bouncer.

He (Julio Gonzalez) was heard to scream drunken threats. He returned to the establishment with a plastic container of gasoline which he spread on the only staircase into the club.

The fire exits had been blocked to prevent people from entering without paying the cover charge. In the panic that ensued, a few people escaped by breaking a metal gate over one door. But the others found no way out.

The Fire Of A Mad Man

After setting the blaze, Julio Gonzalez stood in front of the club and watched it burn. Then he calmly walked across the street and waited for a few minutes as the fire began to take hold. Within moments, fire apparatus arrived and the firemen began to go to work. EMS arrived soon after, parking the ambulance just feet from where Julio Gonzalez stood. He sipped his beer as the first body was carried out the front door of the Happy Land. Then he walked the few yards over to East Tremont Avenue and boarded the #40 bus westbound.

After setting the blaze, Julio Gonzalez stood in front of the club and watched it burn. Then he calmly walked across the street and waited for a few minutes as the fire began to take hold. Within moments, fire apparatus arrived and the firemen began to go to work. EMS arrived soon after, parking the ambulance just feet from where Julio Gonzalez stood. He sipped his beer as the first body was carried out the front door of the Happy Land. Then he walked the few yards over to East Tremont Avenue and boarded the #40 bus westbound.

On the bus ride home, Julio Gonzalez began to cry, thinking about what he had done. He went directly to 31 Buchanan Place, off Jerome Avenue, to his apartment, which consisted of one cramped room. Yvonne Torres, another tenant, later told police she saw him arrive at about 4:15 AM.

Julio Gonzalez entered the lobby and soon knocked on a neighbor’s door, Pedro Rivera. Carmen Melendez, Rivera’s girlfriend, opened the door. Gonzalez told Carmen that he had trouble at the Happy Land and again started crying. He said that he killed Lydia and that he burned the club down. Carmen didn’t believe him and seeing that Gonzalez had been drinking, told him to go home and go to sleep. He went to his apartment, removed his gasoline soaked clothes and promptly fell asleep.

Meanwhile

Meanwhile

At about the same time Julio Gonzalez collapsed upon his bed, a few miles away at the four-eight precinct, Det. Kevin Moroney, a senior investigator with over 20 years with the New York City Police Department, was told about a fire at a nearby social club. “I was doing a turnaround that night,” he said, waiting for his next on-duty tour to begin. “One of the other detectives came running into my office and yelled that 80 people were killed in a fire. My first reaction was what the hell is he talking about? I never heard of such a thing. I didn’t even believe it at first,” he said.

Within minutes, an onslaught of people descended upon the four-eight. Uniformed officers brought in potential witnesses and survivors, the press began to assemble, local district attorneys and assistants appeared, fire department personnel, police department brass, politicians and a platoon of detectives all came to the front desk of the four-eight until the lobby was jammed with a mixture of frantic people all clamoring for immediate and urgent attention.

It was pandemonium. Det. Moroney never reached the front door of the precinct house. “I never made it to the street. Witnesses had to be interviewed, statements had to be taken. We did not know what happened, all we knew was that lots of people were dead,” the detective recalled.

Piecing The Facts Together

Moroney and his partner, Det. Andy Lugo began to piece together a first draft of what happened at Happy Land. Slowly, the story began to emerge. “We finally spoke to Lydia Feliciano later that day. She left the scene and never told anyone where she was. In fact, at the time, no one even knew that she was vital to the case. As soon as she said that she had a fight with her ex-boyfriend and that he left the club angry just before the fire, we had strong suspicions” Det. Moroney said.

At about 4 PM that same day, Detectives Maroney and Lugo went over to 31 Buchanan Place and knocked on the door of Julio Gonzalez’ third floor apartment.

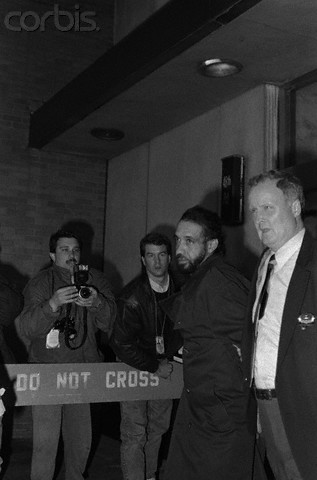

pic credit – Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

When Julio opened the door, the detectives were immediately overwhelmed by the odor of gasoline. They asked him to come over to the police station to talk about the fire. Gonzalez didn’t seem too upset at the time.

Moroney said that he wasn’t surprised to find Julio sleeping. Cops are familiar with the curious sleep habits of criminals. They know that even after the most horrendous crimes imaginable, suspects will fall asleep; in the rear of a police car, at the station, during booking, in cuffs, anywhere at all. It doesn’t matter how violent the crime, how shocking or brutal, a criminal will fall asleep as if he didn’t have a care in the world. Julio Gonzalez put on his gasoline soaked shoes and went quietly with the detectives.

The Devil Got Into Julio González

Julio González was taken over to the four-eight where he was read Miranda Warnings in Spanish and agreed to talk about the incident. Det. Moroney said that he turned to get a cup a coffee and before he could give it to Gonzalez, Julio immediately began to confess. “We practically didn’t even have to ask him anything,” he said.

Julio Gonzalez told police that he set the fire for revenge against Lydia Feliciano. He said that he was angry that she broke up with him and wouldn’t take him back. “I don’t know, it looks like something bad got into me, it looks like the devil got into me!” Julio González said in his confession. He was later arraigned in Bronx Criminal Court at 2 AM on 87 counts of murder, the worst mass murder in American history up to that time. In a highly unusual move, Bronx District Attorney Robert Johnson handled the court appearance himself in front of Judge Alexander Hunter. Gonzalez was held without bail and taken to a local psychiatric ward where he was held as a suicide risk.

A Community In Mourning

Over the next few days, a tidal wave of grief and anguish swept over the South Bronx. More than 60 of the people who died at Happy Land were of Honduran descent. More than 90 children became orphans. Over 40 parents lost their children, some lost more than one. Seventeen players on the county league’s soccer teams were killed in the fire. In nearby Roosevelt High School in the Fordham section, five students died in the smoke and flames of Happy Land. There was almost no one in the Honduran community who was not affected in some way by the tragedy. Even in Honduras itself, the towns and villages of those who were killed were plunged into mourning. The newspapers spoke of little else except el fuego en Estados Unidos.

The Trial of Julio González

The Trial of Julio González

The trial of Julio Gonzalez, which was held in the Bronx in the summer of 1991, was a formality. That’s not to say it was unjust. Rather, in a testament to the principles of due process of law, Judge Burton B. Roberts bent over backwards to ensure the proceedings were conducted in a fair and legal manner.

Of course, the evidence against Julio Gonzalez was overwhelming: his gasoline-soaked clothes, his many admissions to friends on the night of the event, the recovered container, multiple statements of witnesses and his own lengthy and detailed confession to Moroney and Lugo. Testimony as to Gonzalez’ sanity was allowed and, although that avenue of defense was explored, it was ultimately rejected by the court.

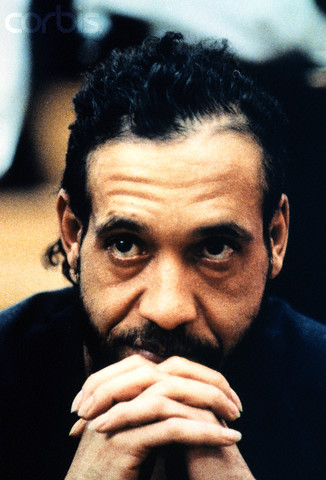

Pic credit – Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

On August 19, 1991, the same day that the notorious anti-Jewish Crown Heights riots began in Brooklyn, Julio Gonzalez was found guilty in one of the worst mass murders in American history. After four days of jury deliberations, he was convicted of arson charges and 174 counts of murder, two for each victim killed in the fire. The verdict, which took over 5 minutes to read, was announced at 1 PM when the jury foreman, Luis Rodriguez repeated the word “guilty” an unprecedented 174 times. Relatives of the victims present in the courtroom, solemn at first, gradually fell apart as the verdict proceeded. Many screamed in grief as the dazed families held onto each other, sobbing uncontrollably. Julio Gonzalez sat transfixed in his chair, a pathetic figure of defeat and despair, his facial expression rigid and unforgiving.

September 20, 1991

On September 19, 1991, Gonzalez was sentenced to 25 years to life on each of the 174 counts of murder, a sentence that was without equal in New York State history. However, he could still be released after 25 years since in New York, any sentence for an act committed during a single offense must be served concurrently, not consecutively. In the courtroom, hundreds of relatives and friends cheered the sentence as Judge Roberts gave Julio Gonzalez the maximum allowed by law. Of course some relatives saw this sentence as an injustice since 25 years equals only 3 months for each murder. In the courtroom, Gonzalez refused to make any statement in his own defense. For whatever it was worth to the families, he would not be eligible for parole until March 2015.

In Memory Of

The street outside the former Happy Land social club (which was located on the northwest corner of Southern Boulevard and East Tremont Avenue in the Bronx) has been renamed “The Plaza of the Eighty-Seven” as a means of memorializing the victims.

Credit Murderpedia / Wikipedia