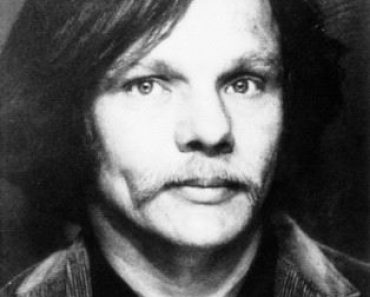

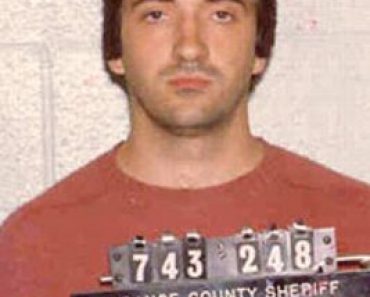

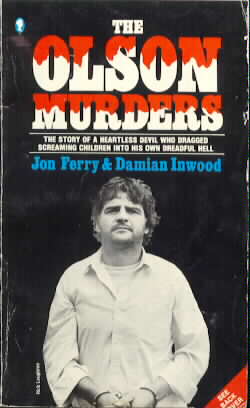

Clifford Olson Jr. | Serial Killer

Clifford Olson Jr.

Born: 01-01-1940

The Beast of British Columbia

Canadian Serial Killer

Crime Spree: 1980–1981

Death: 11-30-2011

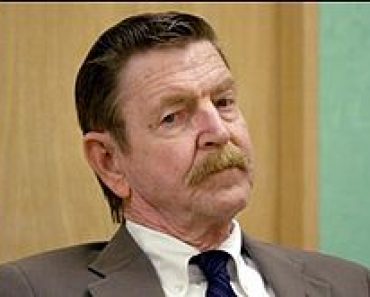

Clifford Olson Jr.

Clifford Olson Jr.

October 3, 2011

Canada’s first true bogeyman, Clifford Olson Jr. is dead.

The country’s pioneer serial killer, whose crimes terrorized the British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, died Friday in Quebec.

Olson’s death was confirmed by the Correctional Service of Canada in a release Friday afternoon. He was 71.

It was learned on September 21st that Clifford Olson Jr. was apparently dying of cancer with only days or weeks to live, according to families of Olson’s victims.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Clifford Olson Jr. was a middle-aged habitual criminal and informant when from January 1980 until August 1981 he stalked, tortured and killed at least 11 youngsters. He sexually abused scores of others.

The heinous nature of his crimes ensured infamy. But more than that, Clifford Olson Jr. is reviled because he blackmailed authorities into paying his family $100,000 for the return of his victims’ remains – a macabre cash-for-corpses deal that destroyed careers and tormented survivors.

Before kinky sex killers Paul Bernardo and Karla Holmolka, before the Pig Farm Butcher, there was the “Beast of B.C.” a.k.a. “the Rent-a-car Killer” because of his penchant for hiring another new car for each slaying. He savored kiddy porn, was a recognized sexual deviant and lived most of his life in a steel and concrete cage.

Back in 1980, however, Vancouver was a truly provincial city – Expo 86 was six years away and newspapers from other provinces or countries still could take days to arrive.

The Lower Mainland was a patchwork quilt of nascent municipalities and a hodgepodge of police jurisdictions. There was little coordination among the different RCMP detachments and autonomous civic police forces, and the computer revolution had yet to occur.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Before he was caught, Clifford Olson Jr. terrorized the province, neighborhoods that once claimed to be so safe you could leave your door open. suddenly locked up tight. Hitchhikers disappeared from the highways and telephone poles were emblazoned with posters warning that nearly a dozen youngsters were missing and a serial killer was on the loose.

In every real way, his (Clifford Olson Jr.) merciless savagery robbed British Columbian’s of their innocence and attendant faith that such monsters only lurked elsewhere.

There were many factors that allowed Olson to prey on children and adolescents across B.C. and elsewhere in Canada for 19 months before being arrested.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Born on Jan. 1, 1940 – a New Year’s Day baby – Clifford Olson Jr. was a bad seed right from the start.

The eldest child of Clifford and Leona, Clifford Jr. grew up in a small house near the Pacific National Exhibition grounds. His dad delivered milk in those days and was one of the last to drive a horse-drawn cart. Later Clifford Sr. worked in construction and as an apartment building manager. Leona was a housekeeper.

After the war, the family moved to the sprouting suburb of Richmond, into one of the many housing schemes for returning veterans. A short, stocky kid, Clifford Olson Jr. was always a problem.

“He was always getting into fights and getting beat up,” his father Clifford Olson Sr. remembered later. “One day he said, `Dad, I’m going to learn to be a boxer. As soon as he did, he began making the rounds of the boys who had beaten him up and started evening the score. Maybe that’s his trouble – that chip on his shoulder.”‘

Clifford Olson Jr. began to skip class when he was only 10 years old, and after completing Grade 8 quit altogether to embrace a life of crime.

Leona bore two more sons, Richard and Dennis, and a daughter, Sharon. All grew up to be law-abiding middle-class people.

But if she could boast of their achievements, with Clifford, she was always making excuses.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Clifford Olson Jr. was a loner, a loser and a perennial failure who was jailed for the first time on July 19, 1957. He was just 17 years old.

Over the following 24 years, he chalked up nearly 100 convictions – obstructing justice, possession of stolen property, possession of firearms, forgery, false pretenses, fraud, parole violation, impaired driving, theft, breaking and entering and theft, armed robbery, escape from lawful custody, rape, buggery, gross indecency … and finally, first-degree murder.

He escaped from jail seven times.

In 1965, for instance, The Vancouver Sun reported the search for him on its front page.

Serving 3 1/2 years in the B.C. Penitentiary for breaking-and-entering theft, Clifford Olson Jr. fled three guards who had escorted him to Shaughnessy Hospital after he feigned illness.

The Search for Clifford Olson Jr.

The chase involved dozens of police and, at one point, the armed-and-dangerous Clifford Olson Jr. slipped through a closing net of investigators in Vancouver’s east end by only seconds. He spent that night hiding under the Queensborough Bridge in New Westminster.

After a week on the loose, Olson was nabbed in Blaine, Wash. – sniffed out by Tiger the police dog.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Border patrol officers had called for assistance after Olson menaced two teens with a gun in a wooded area straddling the international boundary, about a quarter mile east of the Pacific Highway Crossing. Officers from four different forces were involved in the final moments of the chase for the 25-year-old fugitive.

“He must have lain there [in the leaves] three hours with 50 people crisscrossing right through there,” said Chief Border Inspector A.D. Brandon at the time. “But the dog went straight to him.”

It was the second time Olson had been caught by a police dog.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Roughly a year earlier, Clifford Olson Jr. was pinned in a thorny tangle of Richmond blackberry bushes by a police dog named Rinty.

Olson was freed under mandatory supervision five times in the 1970’s and each time his behavior landed him back behind bars.

Released in January of 1980, Olson picked up where he left off and continued his life-long crime spree. It was all he knew how to do.

A few months after getting out of prison, Clifford Olson Jr. seduced Joan Hale, a locally reared divorcee who had survived a violent, abusive marriage. They had a son, Stephen, in April 1981, in the midst of Olson’s killing spree, and they married a month later.

Three days after the ceremony, Clifford Olson Jr. murdered another teenager.

Joan Hale said she knew nothing of the crimes and presented herself at the time as “a victim.”

Olson lived off her divorce settlement and abused her, too, she said.

Hale refused to return the money Olson extorted from then-attorney-general Allan Williams.

His handling of the Faustian pact ended Williams’ career as a provincial politician.

Clifford Olson Jr.

The police investigation of Clifford Olson Jr. – one of Canada’s first serial killer cases – was heavily criticized because he was able to kill again and again, even after detectives identified him as the prime suspect.

Olson was able to initially elude detection in part because of his reputation as a rat -the cops at first thought of him a resource, not a suspect. And they had some reason.

In 1976, inside Prince Albert Penitentiary, Olson was stabbed seven times by a gang of prisoners angry after he betrayed and identified for authorities prison drug couriers.

While incarcerated, Olson also provided police with enough information to ensure the conviction of a fellow inmate who raped, mutilated and strangled a nine-year-old girl.

Clifford Olson Jr., who was always revved up on alcohol and pills, had a standard routine to lure adolescents.

He met them in video parlors and similar youth hangouts or he advertised for them on the bulletin board of the People’s Full Gospel Church, a Baptist congregation where he and Joan worshiped.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Olson handed out a flashy, 3-D card that identified him as a construction contractor.

Under the guise of conducting a brief informal job interview, he identified his potential victims. He sought out the naive.

He’d hold out the prospect of a job, give them a ride to a fictitious construction site and, along the way, offer them a celebratory sip of a Mickey Finn – a pop or bottled cocktail spiked with chloral hydrate, a knock-out drug.

Once he overpowered the youngster, Olson engaged in sadistic experiments on the children. He drove a three-inch spike into one child’s head, another he injected with an air embolism. He talked about them as science experiments and fantasized about fame under the name, “Silver Hammer Man,” a reference to the Beatles’ song.

Clifford Olson Jr. scattered their bodies from the bogs and cranberry fields of the Fraser River delta to the abandoned quarries and canyons of the Coastal Mountains.

He randomly picked his victims from a similarly large swath of the Lower Mainland so the lack of coordination among regional police departments and the RCMP worked to his advantage. The career criminal had honed his awareness of police procedures.

Clifford Olson Jr.

When distraught parents initially complained about police inaction and to speculate about the existence of a serial killer, investigators downplayed such fears. They insisted it was likely the missing teens had run away.

It took investigators an agonizingly long time to link disappearances that occurred in different jurisdictions. In the end, however, even the police were forced to acknowledge the obvious as the number of disappeared neared double digits.

At the investigation’s peak, more than 200 officers were committed to the case. The pressure on police and politicians to find the children and the perpetrator was intense. It was fueled by frenzied media coverage.

“Cunning killer with blazing eyes!” shouted one headline.

“Hot summer helps slayer elude police,” trumpeted another.

A later inquiry identified many problems with the police response to the disappearances and killings. It recommended various independent police departments join in the use of the RCMP computer, the establishment of a central data bank and a review of RCMP procedures for handling multi-jurisdictional crimes.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Nevertheless, two decades later, the lack of integration among Lower Mainland police agencies would remain a problem and be blamed as a contributing factor in the Downtown Eastside missing women case.

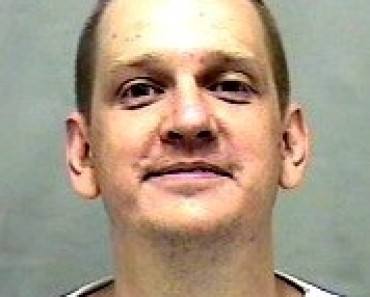

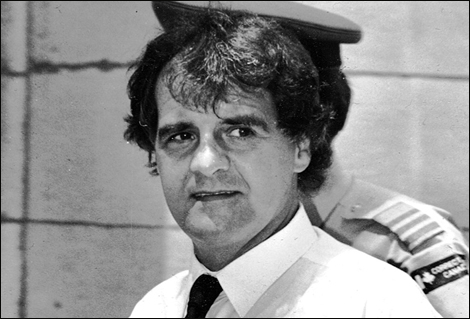

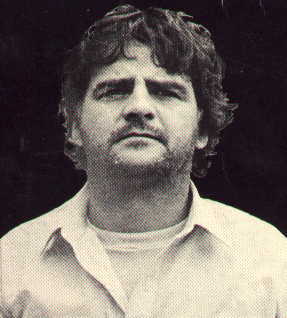

When Clifford Olson Jr. was actually arrested in mid-August, 1981, the Beast turned out to be a banal, beefy rounder with cow orbs. He stood five-foot-seven, weighed maybe 160 pounds and sported a mop of brown hair.

Police, though, had scant evidence against him and only four bodies.

The Interrogation of Clifford Olson Jr.

During his interrogation, Clifford Olson Jr. offered to lead police to the remains of the children who hadn’t been found. He also said he would return some of their jewelry and clothing, which he had kept as souvenirs.

Tapes of the interrogation sessions, notes from investigators and later reminiscences provided a vivid if unsettling picture of what happened.

“I’ll give you 11 bodies for $100,000,” Clifford Olson Jr. told the interrogators.

“You want a $100,000 for 11 bodies,” RCMP Corporal Fred Maile stammered incredulously.

“Yes,” Olson continued, “and you will get statements with the bodies. I will give you all the evidence, the things only the killer would know.”

“Well, just a minute,” said the detective, who later went on to found one of B.C. most respected private investigation companies. “We would have to work something out. I wouldn’t just pay you a $100,000. You could rip us off. Also, I have to have something to tell or show my bosses that, in fact, you are credible.”

“Okay,” Olson replied. “I’ll give you a freebie. I will give you one body and a statement. You have the $100,000 in cash. When we are finished at a scene, I will phone or you will phone your man who will hand the money over to Joan. Then you can talk to your man and I will talk to Joan to make sure that she has the money. Then we’ll go on to get the rest.”

The Deal

“What if your lawyer doesn’t go along with it?” Maile asked.

“Like I told you before,” Olson crowed, “he works for me.”

The killer dictated his proposal and Maile wrote it down on a single page in a sloppy, longhand scrawl:

“This is an undertaking of an agreement between the RCMP and Clifford Robert Olson. The following will be paid by the RCMP to Mrs. Joan Olson for the following information: $10,000 cash for each body of missing persons up to seven bodies. $30,000 for information of four bodies which have already been recovered which relate to the above seven other missing persons. The agreement should be as undertaken shall be binding in law as to not disclose this information in this agreement to the Canadian Press. The following missing persons are covered in this agreement: Judy Kozma, Daryn Johnsrude, Raymond King, Simon Partington, Ada Court, Louise Chartrand, Christine Weller, Terri-Lyn Carson, Colleen Daignault and Sandra Wolfsteiner and one unidentified female (Sigrun Arnd, a German student tourist police weren’t aware was missing). $10,000 will be paid to Mrs. Olson up to a total of the recovery of seven bodies.”

Later, Clifford Olson Jr. called his wife Joan: “Honey, you’re going to be rich.”

Clifford Olson Jr.

As the minister responsible for the legal system, Williams was required to approve what most considered a very real deal with the devil. If Williams didn’t agree to the terms, he was told there was a chance that Olson might slip back onto the street to kill again.

There wasn’t a shred of evidence, the investigators said. The pact was the only way to ensure he was convicted.

It was an excruciating decision.

No one disputes that there is a “secret economy” to the Canadian judicial system, a subterranean marketplace where lawyers and prosecutors haggle over charges, plea bargains and guarantees of immunity. There is a cardinal rule, however, in all such bargains: the criminal should never be allowed to profit. Crime should not pay. Williams and the police could not allow Clifford Olson Jr. to directly receive the money. That would be too great an outrage.

Within days, Clifford Olson Jr. was escorted to an office high in the old verdigris-roofed Sun Tower.

He was not in handcuffs. He strutted around the 17th floor as if he were a celebrity, smoking a White Owl cigar and commanding a handful of lawyers, secretaries, his wife and police.

Clifford Olson Jr.

“Does your husband know what he is doing?” asked Joan’s lawyer, Jim McNeney.

She was catatonic and could only nod mutely.

Olson put a hand on her shoulder and muttered: “What can I say, honey? I did it. It was the booze and the pills.”

She wailed.

Clifford Olson Jr. told the lawyers how he wanted the money distributed – some would pay their fees, some would go to his parents and he wanted to ensure Joan and their baby son were looked after. He suggested his lawyer, Robert Shantz, write a book about the case called, “Kiss Daddy Goodbye.”

The Payoff

After the legal paperwork was signed, RCMP Sergeant Jack Randall unzipped a black, soft sided under-arm briefcase. He withdrew several bundles of wrinkled, old-issue bills bound with elastic bands. He handed them to McNeney’s partner, lawyer Kevin Morrison, who counted the money onto the coffee table.

“One thousand, two thousand, three thousand…”

Olson, the ever-present stogie clamped between his teeth, could barely contain himself. His eyes gleamed. He jiggled Shantz’s elbow.

“…Eight thousand, nine thousand, 10 thousand, 11…”

There were 99 rose-colored $1,000 bills and 10 maroon hundreds.

McNeney later said the scene was so bizarre he half expected a sulfurous explosion and Satan himself to appear. Imagine an honest-to-goodness blood-money deal for bodies. Corpses for cash!

Clifford Olson Jr.

Olson’s family received the cash. In exchange, Williams was able to guarantee a first-degree murder conviction, ease the anxiety of the parents whose children remained officially “missing,” dispel the terror that gripped British Columbia and end an enormously expensive police investigation.

If the deal-making scene had been surreal, the grisly caravan to recover the remains was something from the Twilight Zone.

Olson traveled in a car with four detectives followed by a dog car. Behind, there were usually three or four other vehicles carrying forensic specialists to handle the crime scenes.

Corporal Maile, holding a large tape-recorder, sat in the back seat with Olson, who held a microphone.

The killer wore a regulation RCMP hat as a disguise and dictated as they went, describing the locale and circumstances of each murder with the panache of a sports announcer. The hourly radio broadcasts about the search for more bodies provided a ghastly play-by-play.

Television newscasts featured scenes of excavation teams draining suburban wetlands.

Clifford Olson Jr.

Clifford Olson Jr. liked the forest-cloaked hills around Weaver Lake and the peaty bottom land north of River Road for disposing of his victims. One body was mummified by the time it was found. Others were so badly decomposed only pathologists could identify them.

He pantomimed a re-enactment of each murder, and then police would call McNeney and release the required amount of money. The lawyer deposited it first in the Bank of Montreal at Homer and Hastings in downtown Vancouver but later transferred it offshore to protect it from police seizure.

In between recovering his victims, Clifford Olson Jr. and the police dined at local steakhouses, where the murderer wolfed down thick sirloins and baked potatoes.

He kept scores of mementos to remind himself of each child’s suffering and death throes – trophies to validate his kills.

Clifford Olson Jr.

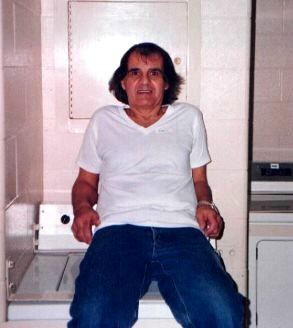

While he awaited trial, Clifford Olson Jr. was the topic of conversation in every courthouse, police station, jail and legal kaffeeklatsch in the province. He even called reporters to brag about the deal he struck and bitch about jail conditions.

“I can’t stand the treatment,” he complained.

The other prisoners tossed trash and lighted cigarettes at him. They shoved him when he passed. While his clothes were in storage, someone ripped the buttons off his suit and scrawled “babyf…er” on his shirt.

“That suit cost $200,” he whined. “The shirt $60. I don’t have to put up with that kind of s—. I think one should have fair treatment from the press. I want to be segregated from other inmates. I have to sleep on the floor. I have to live like a dog. I’ve got no running water. I’ve got no light in my cell. I’m locked up 22 hours a day. I get one hour exercise in the morning.”

Olson’s whinging generated front-page news, but no one in the B.C. media reported the deal.

The attorney-general had personally wooed publishers and broadcast executives not to reveal the pact. Even when questions about the payoff were raised in the House of Commons, they censored the information. What was front-page news in Edmonton, in B.C. was an enigmatic brief.

Clifford Olson Jr.

No one in B.C. wanted to be blamed for violating the serial killer’s right to be presumed innocent before the verdict was pronounced.

In the end, the trial was aborted by Olson’s guilty pleas. He dabbed away tears as he confessed publicly for the first time.

After the court clerk read each charge of first-degree murder, Olson replied hoarsely: “Guilty.”

Tears streamed down his cheeks after the 11th and final first-degree murder charge was read.

Justice Harry McKay said no punishment a civilized country could impose was adequate.

“You should never be granted parole for the remainders of your days. It would be foolhardy to let you at large.”

Indeed, as he was driven away to serve his sentence, Clifford Olson Jr. confided to the accompanying officer that if he ever regained his freedom, “I’d take up where I left off.”

Clifford Olson Jr.

Clifford Olson Jr. was sentenced to 11 consecutive life terms. He died in prison on October 2, 2011

credit murderpedia / Ian Mulgrew – Vancouver Sun