Andras Pandy

The Family Killer

Family Killer

Crime Spree: 1986 – 1992

The digger grabbed the fingers of his mud-encrusted black rubber gloves with his teeth and gave them a sudden tug. For just an instant he thought he might swoon from the overpowering stench of diesel fuel and raw sewage that seemed to seep from every crevice in the dank cellar.

He choked back his own bile as he stuffed the glove into the breast pocket of his police issued Vulcanized rubber waders. The moment that the foul air touched his bare skin, a chill ran down the digger’s spine and he suddenly felt somehow unclean. He picked up the galvanized metal sieve filled with mud and gave it a shake. Thick black slime oozed from the bottom of the pan, leaving behind, what? A pebble, a tiny shard of glass, a tattered piece of cloth…and…what was that? That small white fragment there in the mud?

His imagination was getting the best of him, the digger told himself.

He needed to focus. This was a crime scene. Nothing more. He was a professional and his job was to collect evidence, however small, bag it, tag it, and send it upstairs. He wasn’t there to make judgments.

It was up to the detectives, the elites upstairs from the Belgian Ministry of Justice, to put it all together and decide what it all meant. They would decide whether the evidence showed that this was the house of an innocent man of God or whether Andras Pandy, the rumpled little clergyman with the odd Hungarian accent, really was the monster he was accused of being.

Andras Pandy

It was up to them to determine whether Pandy’s daughter had been telling the truth when she accused her father of seducing her and then conspiring with her to murder six members of their family. They would decide whether it was true that together father and daughter had hacked up their family — Pandy’s first wife, his daughter’s mother, his own son and young daughter — and dissolved the pieces of their bodies in an acrid bath of acid. All the digger had to do was pick up the pieces.

He reached into the filth at the bottom of his sieve and tentatively probed the tiny white fragment with his finger. It was exactly what he had thought it was.

It was a human tooth. There beside it was a splinter of bone, a piece of a kneecap, a small bit of human flesh and beside that, a chunk of human skull.

Case Closed and Forgotten

It was two years earlier, in 1997 and an army of Belgians – 350,000 out of a nation of 10 million – had marched in silence through the streets of Brussels. It was much more than simply a candlelight vigil, the kind of spontaneous demonstration of grief and outrage that have become common in the aftermath of brutal crimes. This demonstration – which became known as the White March – a massive protest against the government’s bungled investigation into a series of kidnappings and murders in Belgium.

Some in the crowd had even accused the government of participating in a cover up of the crimes of a killer named Marc Dutroux. In fact, a parliamentary inquiry into the cases had found that police and prosecutors had so thoroughly botched the Dutroux affair that their actions “put at risk the state of law.” It seemed as if all the institutions of Belgium had been tainted, the police, the courts, the government itself. Shaken Belgians wonder aloud whether there was any institution in the nation that could be trusted.

So deep was the outrage over the killings and the government’s handling of them, that some thought the upheaval might threaten to destroy the Maryland-sized country, to rip it apart along ethnic lines, dividing French speakers from Flemish speakers.

“Corruption and spinelessness are eternal,” Hugo Claus, the nation’s most revered Flemish writer said in a newspaper interview at the time. “Stupidity and mediocrity accompany our existence and in Belgium, this is amplified.”

Andras Pandy

For the authorities in Belgium, the Dutroux case – and the explosion of public anger that had followed it — had been their Waterloo. In its wake, investigators and prosecutors were facing intense scrutiny. They were under immense pressure to prove that they were not bumbling misfits and that the public could have faith in them.

That was why investigators began combing through old records, going back a decade or more, reviewing almost every case they had closed, looking for oversights and errors.

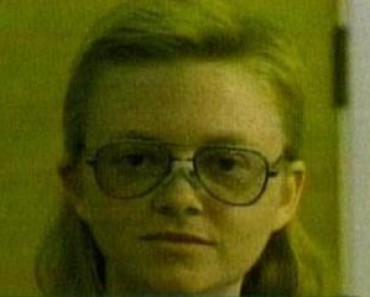

It didn’t take long to find one. At first, the case didn’t look like much, a fairly routine complaint, five years earlier by a young woman named Agnes Pandy, the mousy then 38-year-old daughter of a protestant minister, a quiet but diligent woman who spent her days working in the map department of the Albert First Royal Library.

Her whole demeanor made her easy to ignore. A lackluster young woman, blank unblinking eyes behind nondescript spectacles, she seemed to be the kind of person who wandered around the fringes of life, always overlooked. Perhaps she had issues with her father. Women like that often do, authorities thought. She certainly had seemed a little odd when she first walked into police headquarters claiming that her father had turned her into his sex slave.

Andras Pandy

But she also seemed sincere when she told police that she was worried.

She said that four years earlier her father had sent her and her older brother on holiday to the Belgian coast for several days. When they returned, she told police at the time, her stepmother, Edith Pandy and her sister, Andrea, had vanished.

“Don’t look for them,” she recalled her father telling her on her return. “They’re not coming back.”

But in the end, her complaints went nowhere. Investigators had looked into the case back then – without much enthusiasm – and had come up empty. There was no evidence to support her claim that she had been sexually assaulted. Nor was there any evidence that her father’s parsonage was, as the newspapers would later call it “A House of Horrors.” Investigators had spoken briefly with the minister and he had offered a perfectly plausible explanation for his wife and daughter’s absence. “They have returned to Hungary” he told authorities. He had even offered them proof that the missing family members were alive and well in Eastern Europe. He had a stack of letters purportedly written by them and postcards mailed from places like Israel, Miami and Brazil.

His explanation certainly seemed satisfactory. The investigators thanked the disheveled parson for his time and moved on, closing the case, confident that the whole thing was just a bizarre tale spun by a frustrated spinster, filled with resentment for her respectable father.

Andras Pandy

Certainly, Andras Pandy might have seemed a little eccentric, but he was a minister, a respected part of an institution in Belgium, and in the early 1990’s, at least, institutions in Belgium were still to be trusted and respected.

Of course, that was back in the days before L’Affaire Dutroux had shaken the foundation of all the institutions in Belgium. Times had changed, authorities thought. Maybe it was time to revisit the Andras Pandy case one more time.

A Walk in the Courtyard

Francois Monsiuer was starting to get frustrated. Then a senior prosecutor in Brussels Judicial Police criminal unit, Monsiuer had been listening almost sympathetically to Agnes Pandy’s rambling statements for hours but it seemed to the veteran prosecutor that something was missing. The newspapers were already reporting her bizarre allegations against her father. “I am ashamed that my father might turn out to be one of the worst serial killers in history,” she told a Belgian newspaper. But there were great gaps in her halting tale.

Monsiuer gently suggested to her that, perhaps, a walk through the courtyard of the Brussels Judicial Police building might clear her head.

And so she strolled, her heels clicking on the blocks in the courtyard, while a few paces behind her, police kept close watch on her. The ornate and terribly civilized facades, the carefully tended plantings, the sculptures that adorned this corner of Brussels all seemed so calming and orderly, a far cry from the squalid industrial neighborhood where Pandy had lived with her father, a place that reeked of sewage and slaughterhouses. If she had to summon the ghosts of slaughtered family members, though, perhaps this was a good place to rally them.

A half an hour later, she returned, leaned forward and softly said to Monsiuer, “I am going to tell you how we killed five people.”

Andras Pandy

Her tale was one of imaginable horror, a grand guignol of murder and rape and depravity at the house on Quai de l’Industrie in the rundown quarter of Brussels known as Molenbeek. She talked of how her father, a bookish churchman, had seduced her when she was just 13, raped her is perhaps a more accurate phrase, and how she felt she had no way of escaping him. “I had no way out,” she would later tell authorities. Her will had been totally subjected to his. As her defense attorney would later tell a jury, “she had been under the overwhelming irresistible spell” of her father.

By the time she was finished talking, Agnes Pandy had implicated her father – and herself – in five homicides, all members of their family.

The body parts that would later be pulled from the mud in Pandy’s murky basement, the slabs of unidentified “meat” pulled from his freezer, would offer an even more chilling glimpse into the horror.

DNA tests conducted on them would reveal that the bones and teeth and fragments of flesh were indeed human, but did not match any of the missing members of the Pandy family. That, authorities said, meant that there were in all probability other victims.

Andras Pandy

Perhaps, they would later speculate that as many as 13 people fell victim in Brussels to Pandy’s blood lust. Some of them, they speculated might have been innocent women lured from Pandy’s native Hungary through newspaper ads he had placed there searching for a bride.

She spelled out in graphic detail how she and her father, described by a fellow churchman as “unfathomable and mysterious,” with a constant smirk, “a little smile, like Buddha,” had killed their victims. Some were shot. Others bludgeoned to death with a sledgehammer. Then they hacked their victims to pieces and stuffed their remains in plastic bags, dumping some at a nearby abattoir, dipping others into a vat brimming with 21 liters of Cleanest, an acid cleanser that ate all the meat from the bones and then dissolved the bones themselves.

The full scope of the horror was beyond comprehension, Monsiuer thought. Much of it, as Monsiuer would soon learn, would be beyond the powers of the Belgian authorities to prove. But there was certainly enough evidence, what with the viscera that had been collected at Pandy’s house and with the damning statement of his daughter, to prove that Andras Pandy was a deranged killer in a cleric’s frock.

Killer in a Cleric’s Frock

The newspapers in Brussels would later call him “The Diabolical Pastor,” but there was nothing in Andras Pandy’s calm and quiet demeanor that would indicate the depth of his potential for depravity, authorities said.

Short and disheveled, with a bit of a paunch and a mane of unkempt gray hair, he was articulate but reserved when dealing with strangers. A refugee, he had fled his native Hungary after the bloody uprising against Soviet authority there in 1956. He ultimately drifted to Belgium where he managed to find work, first as a pastor at a church for fellow Hungarians who had also fled the community regime, and then later teaching religion in Flemish schools.

At about the same time that he fled Hungary, Pandy married his first wife. Her name was Illona Sores, and she bore the pastor four children, the eldest was Agnes.

By all appearances, the family was the picture of propriety. Pandy was a clever businessman, authorities would say, who traded on his public image as a man of God for profit. He founded an organization — Ydnap, his own name spelled backwards – providing foster care for children orphaned during the revolution in Romania that ousted dictator Nicolas Ceausescu, the Hungarian newspaper Nepszava reported. Authorities believe he used that foundation to raise enough money to buy two houses in Brussels, authorities said.

Andras Pandy

But behind the closed doors of one of those houses, a 19th Century manse where the Pandys lived, the picture was quite different. The family was a study in dysfunction.

As investigators would later learn, the slightly effeminate preacher was a brutal martinet in his own home. He was, as a report in a European newspaper would later put it, “an authoritarian bully…a sexually voracious predator who advertised for partners in the Hungarian press, and an abuser of his own children.”

In 1967, after 11 years of marriage, Sores and Pandy divorced. Sores mysteriously vanished. For his part, Pandy explained that she had simply returned to Hungary.

Authorities would later discover that Sores had been one of the victims of the killer cleric and his sex slave daughter.

In the meantime, Agnes, it now appears, had become at least one of the objects of Pandy’s rapacious sexual appetite. She would later tell authorities, she was just 13 years old when her father began sexually abusing her. She would describe herself as his sex slave, according to published reports.

The sexual abuse, authorities would later say, continued even after 1979 when Pandy met and married his second wife, a single mother of three children named Edith Fintor, whom he had found through an advertisement he placed in a lonely-hearts column in a Hungarian newspaper. She would later bear the Priappan preacher two more children.

Andras Pandy

Fintor’s young daughter Timea appealed to Pandy’s sordid sexuality as well, authorities said. He began a lengthy sexual relationship with the young girl. He was, authorities say, as secretive about his liaisons with his daughter and stepdaughter as any predatory pedophile might be. But when at last it seemed as if his secret might be revealed, Pandy, authorities charged, was ready to go to unthinkable lengths to protect himself.

That became clear in 1986, Agnes Pandy told authorities, when Timea became pregnant with her stepfather’s child. Authorities now believe that Timea’s pregnancy may have been the catalyst for Pandy’s killing spree. Timea’s stepfather wanted her dead. Her stepsister, Agnes tried to oblige him.

Agnes later admitted that she tried to bludgeon her sister, but her sister managed to escape and fled with her infant son, first to Canada and then back to Hungary. Somehow, she managed to remain out of Pandy’s reach.

Other members of Pandy’s family were not so lucky.

It Felt Cold

For years, Agnes had been silent. Silent about her own abuse, silent about the unnatural series of killings on which she and her father had embarked. Of course, she had tried to tell the story, or at least part of it, before. But no one had been listening. So she simply remained silent.

They were listening now. For two days in October of 1997, she talked. Her confession took several hours, authorities would later say.

It was, she told authorities, at her father’s behest that she killed her own mother. Together, between 1986 and 1992, they killed her stepmother and three of her siblings. They disposed of the bodies in the most gruesome way.

When the case finally made it to court earlier this year, jurors would get a taste of just how awful that disposal had been.

Forensic scientists, working for the prosecution, took body parts harvested from a man who had died of natural causes, and as a video camera recorded the experiment, they dumped the viscera into a vat of Cleanest. The household cleanser has since, for reasons unrelated to the Pandy case, been pulled from the market.

The acid bath worked just as Agnes had claimed. The remains of the man who had donated his body to science simply vanished into the frothy pool of chemicals.

Andras Pandy

When the tape was played in court, Pandy was unmoved. But Agnes averted her eyes.

The gruesome image on the screen seemed, observers would later say, to bring all the horror back to Agnes. Illen Sores, Edit Fintor, her daughters, Andrea and Tunde. Agnes own brothers, Zoltan and Daniel. Their deaths were brutal. Their dismemberment was even more savage. Seeing it stunned her back into silence.

But as she sat in Monsiuer’s office on that October afternoon in 1997, she was anything but silent. She told the police how she and her father chopped up the corpses using kitchen knives and axes before dissolving the remains. She told them how she had eviscerated one of her own stepsisters with her own hands. “It was my task to take out the organs while Pandy was cutting up the remains,” she said. “I just used a kitchen knife . . . you have to exercise strength. It’s not that easy.”

The only real sensation she could recall, she would later testify was this: “It felt cold.”

A Clever Liar

How was it possible, the newspaper pundits wondered, that such a brutal and prolonged killing spree could go undetected? Surely, it had to be the incompetence of the judicial system, the police, the prosecutors. Surely, they had failed, the critics opined.

And perhaps, to some degree they did. Perhaps they could have been more aggressive when word first leaked out that something unsavory might be going on at the house in Molenbeek.

But perhaps there was another reason that the diabolical pastor managed to escape detection for so long. Perhaps it was that Pandy himself took great pains to cover his tracks, authorities said. He was, prosecutors would later say, a very “clever liar,” and a talented actor.

Take, for example, the dramatic portrayal of a jilted husband that Pandy has said to have given in 1986 at the front desk of a Brussels police station not long after – as authorities would later learn – he murdered his second wife.

Appearing agitated and distraught, the parson stormed into headquarters to report that his second wife – a woman, he claimed, he had rescued from the evils of a communist country, simply up and left him. “She had gone to live in Germany,” he told police. His performance was convincing, authorities would later say.

Andras Pandy

But that is hardly the most elaborate performance the theatrical preacher gave, authorities said.

Not long after Pandy’s arrest, police in Hungary discovered what may have been his most elaborate ruse. Claiming that he was writing a screenplay about his life, he hired two young actors to impersonate two of his missing children during his occasional forays back to his native Hungary. Pandy had purchased a tiny green cottage in his old hometown. He called it a refuge from his life in Brussels. “He took the children on family visits,” then asked his friends and family to “write letters saying they had seen the children,” police said at the time. A widow, who would later be wooed by Pandy and later became dangerously close to him, remembered that Pandy brought two young women to her house one day about a year before his arrest. “They were about 22 or 24, and their names were Andrea and Tunde,” Margrit Magyar told a reporter. “But I later learned that these were the names of two of the girls that were supposed to have disappeared.”

The young women told police they played their parts several times between 1992 and 1996, and never suspected a thing. They believed that the ruse was “rehearsal for a part on a movie about Pandy’s life,” authorities said.

A Vague Suspicion

Not everyone was swayed by Pandy’s performances.

Istvan Stweszek, a retired minister in the Hungarian Protestant Church in Belgium and a former colleague of Pandy’s, told the Irish Times in a 1997 interview that he had long had a disquieting feeling about his fellow pastor even before Fintor’s disappearance.

“We often had the impression that his wife was not only his wife, but also his servant and slave,” Steszek told the newspaper.

In fact, as early as 1989, a pastor in the nearby Netherlands who knew both Pandy and his second wife well enough to be concerned about Fintor’s sudden disappearance, wrote to police and to Queen Fabiola, urging the government to investigate.

The letters were examined, authorities said, and a missing persons report was filed. But when police spoke to Pandy, he put on yet another grand performance, telling them that he had heard from his estranged spouse and that the news was all grim. She remained in Germany, he told them, and had fallen gravely ill. As a matter of fact, he said, she seemed to be near death.

Andras Pandy

Ironically, at about the same time, workers rebuilding a canal alongside Pandy’s house unearthed a handful of human bones. No attempt was ever made to link those remains to Pandy’s missing family members.

It was in 1992 when a friend of a high-ranking police official suggested that someone might want to talk to Agnes Pandy, the pastor’s daughter.

They did. They met with her. They listened to her. For seven hours, they listened. And then they turned to Andras Pandy.

Angrily, he denied his daughter’s allegations of incest and worse. He accused her of being pathologically jealous, and suggested that she was secretly a member of a strange sect.

Besides, he told them, it was he who had first reported his wife missing, and with his emotional state at the time, certainly that was proof enough that he had borne his wife no ill will.

Besides, he said, brandishing a stack of letters, he had evidence – in black and white – that his children were alive.

In August of that year, the incest case was closed. A few months later, the police notes, the records of the phone calls, the transcripts of their interviews were all shuffled into a file marked “no further action,” and buried in the deepest recess of a Brussels police station.

Andras Pandy

But five years later, as the nation reeled from the shock of the Dutroux scandal, the Pandy file would be exhumed. Soon thereafter, police diggers in vulcanized rubber boots would slowly descend the basement stairs in Pandy’s home, easing their way along the blood stained wall, to begin sifting through the muck, searching for fragments of unthinkable horror.

It was February of 2002. The “Pastor Diabolique,” as he had been dubbed by the Belgian press, seemed vaguely amused as officers led him past the throng of reporters and photographers into the courtroom in the vast marbled hall of justice. That smile, that ever-present smile; that Buddha-like smile, as his former colleague had described it, never seemed to fade from his face, observers would later note.

Throughout his two-week long trial, as he sat next to his co-defendant, who was also his chief accuser, his former sex partner and his daughter, Pandy seemed hardly to be moved by the proceedings.

But the people of Belgium were deeply disturbed. For them, the case, as horrible as it was, was also an indictment against the police, the prosecutors and the courts.

For them, it dredged up again the revulsion they had felt when word of Dutroux’s atrocities against young girls – and the government’s impotence in the face of his crimes. It reminded them of the government’s botched investigation a decade earlier into the Killers of Brabant, who between 1982 and 1985 shot dead 28 shoppers in gun attacks on supermarket car parks around Brussels. In that case, hooded murderers, always driving the same Volkswagen Golf GTi would open fire at random with pump-action shotguns, and then escape, evading police roadblocks and even crack military units as they fled, leaving hundreds of wounded people behind them. No one has ever been charged.

Andras Pandy

Andras Pandy, the smiling, bespectacled pastor accused of a horrific string of murders was just one more example of how the authorities had failed to fulfill the most basic responsibility of any government – to protect its citizens.

To make matters worse, this was to be a trial with no bodies. The bone fragments plucked from the mud in Pandy’s basement had been studied and tested, but authorities were never able to determine whose remains they were. They were the remains of men and women, all of them over the age of 35, but their identities remained a mystery.

As a result, the indictment against Pandy and his daughter named only the five victims who had been bound to him by blood or marriage — his two former wives and his three children. Of them, not a trace remained. What’s more, his stepdaughter Timea, who had carried his child and survived his alleged attempt against her life, refused to testify against him in court. She told authorities that even after nearly twenty years, she still feared the man.

In court, Pandy seemed to relish the fact that even now – nearly 20 years after his killing spree ended, police still had no hard physical evidence with which to confront him.

At one point, he challenged the prosecutors to prove that his family members were dead, claiming that they were “alive and well” and in the care of some unspecified “international society.”

“It is up to justice to prove that they are dead,” he said. “When I’m free again, they will come and visit me.”

Later, he appeared to almost taunt the prosecution, claiming that he was “in contact,” with his missing children, then added, “through the angels.”

The Verdict

But the prosecutors were relentless, observers would later say. In hindsight, it may have been their decision to show the grisly videotape of body parts being dissolved in the same acidic cleanser that Pandy allegedly used on his family, which made the difference.

Perhaps it was the Prosecutor General Alain Winant’s chilling depiction of Pandy as a pastor who felt that he could act “as a God in every sense of the word,” a man who “has reached such a level of virtuosity when it comes to lying that one can really speak of a form of art in his case.”

Perhaps it was Pandy’s own rambling denunciation of the case against him as a “witch trial” during a closing statement that observers said confirmed what court appointed psychologists had found when they described him as “paranoid, hostile and anti-social.

“Here in the capital of Europe I have been subjected to a trial for sorcery,” he told the jurors in a statement peppered with obscure references from the Bible, about the fall of the Roman Empire and the trial of Socrates. “At every turn, the proceedings have been very black, full of tragedy, full of Satanism.”

After twelve hours of deliberation, on March 8, a jury convicted Pandy of six counts of murder. He was also convicted of raping his daughters.

Andras Pandy

Agnes Pandy was convicted of five counts of murder, and of the attempted murder of her stepsister Timea. Now 44, Agnes Pandy was sentenced to 21 years in prison.

Her father was sentenced to life.

Epilogue

The thought that Andras Pandy will, in all likelihood, die in prison is small comfort to a nation that is still trying to come to terms, not only with his years-long orgy of violence, but with it’s own mistrust of the authorities who are deputized to protect it.

Nor does it fully or finally put to rest the question of whether justice was really done for all of Pandy’s victims. After all, the police diggers who first encountered the terrible detritus of death in that dismal basement nearly five years ago, recovered fragments from likely victims whose stories have never been told. No one really knows who they were, or how they spent their last few moments on earth. In all probability, authorities admit, those questions will always remain unanswered.

But there is some small solace in the final judgment on Andras Pandy and his daughter.

Timea, his stepdaughter, for one is safe.

So is her son, now 20 years old.

And in a remote corner of Hungary, there are two women Eva Kincs and her elder sister Margit Magyar who spend their summers tending the garden of their tiny house, not far from the Danube and closer still to Pandy’s summer house. Perhaps they are as relieved as anyone on earth that Pandy is now behind bars.

Andras Pandy

In the months before his arrest, Andras Pandy courted Magyar, and unbeknownst to her, he also courted her sister. Each of them believed that she would become his third wife, and when he invited them both to come and stay with him for a time at his home in Molenbeek, they eagerly agreed.

While there, they told reporters later, he pressed the two women into service. They cooked and cleaned for him, and he kept them locked up tight in his home.

“We were in the house. All the doors were locked and he had the key,” Kincs said. He told them that they would raise suspicions if they wandered out on the streets of Brussels unable to speak anything but Hungarian. During their stay, he took them out only once, Kincs later said.

A week into their stay, the two women compared notes, and when they discovered that Pandy had proposed to both of them, they angrily demanded that he send them back to Hungary.

Surprisingly enough, he did.

Andras Pandy

The two women will never know for certain whether the fate shared by Pandy’s first two wives and his three children also awaited them.

Still, Kincs said, “we feel like survivors.”

source: murderpedia | crime library | Seamus McGraw

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links