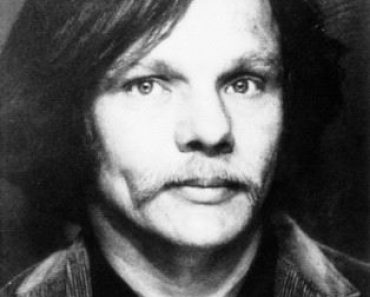

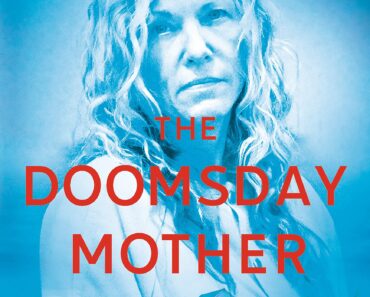

Tormented by their crying, Waneta Hoyt killed five children, one by one. All her own!

Tormented by their crying, Waneta Hoyt killed five children, one by one. All her own!

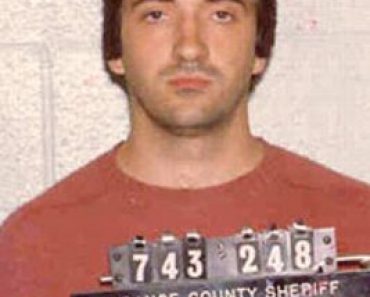

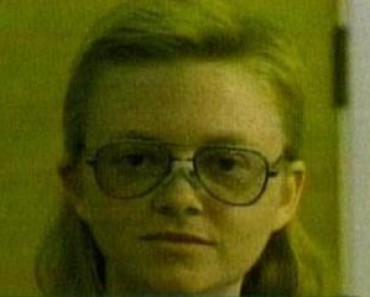

For more than 25 years, Waneta Hoyt would drive each Memorial Day to the small cemetery beside her childhood home in Richford, N.Y., to lay flowers on the graves of her babies. Over a 6½-year period, from 1965 to 1971, five of them, Eric, Julie, James, Molly and Noah, ranging in age from just 48 days to 28 months, had died one by one, victims of what doctors classified as sudden infant death syndrome.

Scratching out a modest living in the farming community of Newark Valley, some 70 miles south of Syracuse, Waneta Hoyt, a home-maker, and her husband, Tim, for many-years a security guard at Cornell University’s art museum in Ithaca, were regarded as a quiet couple who bore stoically their unfathomable loss—though Waneta occasionally betrayed a flicker of guilt. “She’d say, ‘I don’t know what I did wrong,’ ” recalls former neighbor Georgia Garray. “We used to tell her, ‘You’re not a bad mother.’ “

But little did they know

On September 11, Tioga County Judge Vincent Sgueglia sentenced Waneta Hoyt, 49, to 75 years-to-life in prison for “depraved indifference to human life,” in this case a devastatingly apt euphemism for murder. In April an Owego, N.Y., jury ruled that Waneta Hoyt had suffocated each of her children—with pillows, a towel, even her shoulder. “Five young people aren’t here today because of her,” Tioga County prosecutor Robert Simpson told the jury in closing arguments during the four-week trial. “They would have had families, jobs. But they don’t get that opportunity because their mother couldn’t stand their crying.”

On September 11, Tioga County Judge Vincent Sgueglia sentenced Waneta Hoyt, 49, to 75 years-to-life in prison for “depraved indifference to human life,” in this case a devastatingly apt euphemism for murder. In April an Owego, N.Y., jury ruled that Waneta Hoyt had suffocated each of her children—with pillows, a towel, even her shoulder. “Five young people aren’t here today because of her,” Tioga County prosecutor Robert Simpson told the jury in closing arguments during the four-week trial. “They would have had families, jobs. But they don’t get that opportunity because their mother couldn’t stand their crying.”

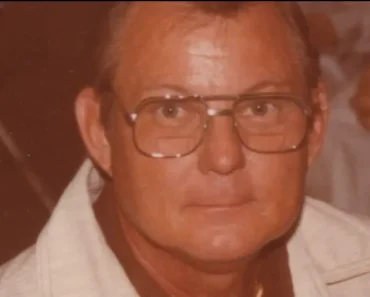

Last month, as she contemplated a life behind bars, it was Waneta Hoyt’s turn to weep. Claiming her statement to police—in which she confessed to the murders—was coerced, she declared after her conviction, “I didn’t kill my babies. I never did nothing in my life, and now to have this happen?” Suffering from a variety of ailments including high blood pressure and osteoporosis, and looking far older than her years, she was comforted by the supportive arm of husband Tim, 52, and the presence of their surviving, adopted son, Jay, 19. “Despite the cruelty of her acts,” said William Fitzpatrick, district attorney of neighboring Onondaga County, after viewing Hoyt’s broken-down appearance, “you’d be less than human not to have some degree of sympathy for her.”

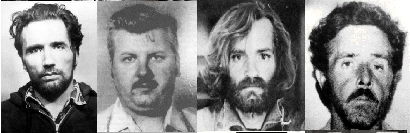

A killer in Syracuse

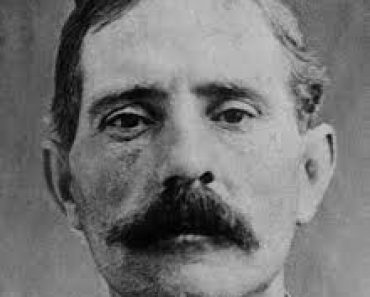

It was William Fitzpatrick, 48, who first began investigating Waneta Hoyt. In 1985, while prosecuting a case of murder originally diagnosed as SIDS, he consulted forensic pathologist Linda Norton of Dallas. In the course of their conversation, Fitzpatrick recalls, Norton made an offhand remark: “You know, you have a serial killer right there in Syracuse.”

It was William Fitzpatrick, 48, who first began investigating Waneta Hoyt. In 1985, while prosecuting a case of murder originally diagnosed as SIDS, he consulted forensic pathologist Linda Norton of Dallas. In the course of their conversation, Fitzpatrick recalls, Norton made an offhand remark: “You know, you have a serial killer right there in Syracuse.”

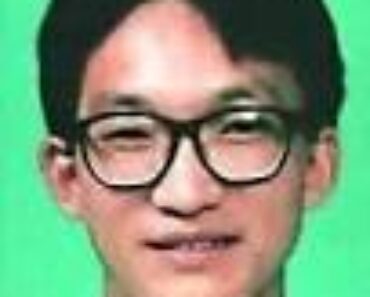

Norton had read a 1972 medical-journal article by pediatrician Alfred Steinschneider—Hoyt’s physician—describing the “H” family in which five children had succumbed to SIDS. Norton, an expert on SIDS, told Fitzpatrick the odds against five such deaths in one family were incalculably high. She also found it suspicious that the mother was always alone with the babies when they died.

Shortly thereafter, Fitzpatrick left the prosecutor’s office, but Norton’s comments still gnawed at him. And in 1992, when he was sworn in as DA, he immediately began tracking down the H family, soon identified as the Hoyts. Fitzpatrick pulled the autopsy records on the Hoyt children and sent them to New York State Police forensic expert Michael Baden for review. In each case, Baden told him, the records did not support the stated cause of death. “They were all healthy children,” says Baden. “They had no natural cause for death. The only reasonable cause is homicidal suffocation.”

Suspicions Suppressed

In fact, as one Hoyt baby after another died, some health-care professionals did grow suspicious at the time. Four nurses who testified at Hoyt’s trial said that Waneta showed little interest in the babies. “There was no bonding at all,” said Thelma Schneider. “Most of us went to Dr. Steinschneider and expressed our fears—we had a gut feeling that something was going on. Either he was in total denial or not being very objective.” Ambulance worker Robert Vanek, who went to the Hoyt residence when Julie, James and Noah died, recalled being stunned by the coroner’s conclusion that all had died of SIDS. Says Vanek: “I thought, three in a row? It bothered me.” As for the faulty SIDS postmortem diagnoses, Baden says the children’s bodies were examined not by dispassionate forensic pathologists but by family physicians. “Doctors,” he says, “don’t want to think parents harm children.”

In fact, as one Hoyt baby after another died, some health-care professionals did grow suspicious at the time. Four nurses who testified at Hoyt’s trial said that Waneta showed little interest in the babies. “There was no bonding at all,” said Thelma Schneider. “Most of us went to Dr. Steinschneider and expressed our fears—we had a gut feeling that something was going on. Either he was in total denial or not being very objective.” Ambulance worker Robert Vanek, who went to the Hoyt residence when Julie, James and Noah died, recalled being stunned by the coroner’s conclusion that all had died of SIDS. Says Vanek: “I thought, three in a row? It bothered me.” As for the faulty SIDS postmortem diagnoses, Baden says the children’s bodies were examined not by dispassionate forensic pathologists but by family physicians. “Doctors,” he says, “don’t want to think parents harm children.”

Because the Hoyts lived outside his jurisdiction, Fitzpatrick turned the case over to Tioga County DA Simpson. In March 1994, New York State trooper Bobby Bleck, a family friend of the Hoyts, approached Waneta at a local post office and asked for her help with research he was doing on SIDS. At the station house, Bleck, with police investigators Susan Mulvey and Robert Courtright, took Waneta Hoyt, step by step, over the official version of her babies’ deaths. After about an hour, Mulvey gently clasped Hoyt’s hand and told her they didn’t believe her.

The confession of Waneta Hoyt

Fifteen minutes later, Waneta Hoyt confessed to having killed all five children. Her candor was chilling. “I suffocated Eric in the living room,” she began. “He was crying all the time, and I wanted to stop him. Julie was the next one to die. I cradled her up to my shoulder. When she quit crying I released her, and she wasn’t breathing.” In September 1968, Waneta Hoyt said, she was dressing in the bathroom when a tearful, agitated James tried to break in on her. “He kept screaming, ‘Mommy, Mommy,’ ” she recalled. “I used a bath towel to smother him. He got a bloody nose from fighting against the towel.” Molly was next, suffocated with a pillow, at age 2½ months, as was Noah one year later. “I didn’t want them to die,” their mother told police. “I wanted them to quiet down.”

Fifteen minutes later, Waneta Hoyt confessed to having killed all five children. Her candor was chilling. “I suffocated Eric in the living room,” she began. “He was crying all the time, and I wanted to stop him. Julie was the next one to die. I cradled her up to my shoulder. When she quit crying I released her, and she wasn’t breathing.” In September 1968, Waneta Hoyt said, she was dressing in the bathroom when a tearful, agitated James tried to break in on her. “He kept screaming, ‘Mommy, Mommy,’ ” she recalled. “I used a bath towel to smother him. He got a bloody nose from fighting against the towel.” Molly was next, suffocated with a pillow, at age 2½ months, as was Noah one year later. “I didn’t want them to die,” their mother told police. “I wanted them to quiet down.”

Few Clues As To Why

Hoyt’s life history yields few clues to her murderous bent. She was the sixth of eight children born to Arthur Nixon, a Richford, N.Y., laborer, and his wife, Dorothy, a seamstress. Waneta met Tim Hoyt on a school bus in ninth grade. Two years later, at 17, she dropped out of high school to marry him, and within nine months she gave birth to Eric. Forty-eight days later, confessed Waneta, she killed him. “I asked God to forgive me over and over and over,” said Hoyt, who had sought counseling after the last death.

Despite the explicitness of her confession, Hoyt’s family staunchly supports her claim that police twisted her description of the deaths into a confession. “She was used like an old tire,” says Tim, now a factory worker. Adds Jay, whom the Hoyts adopted when he was 7 weeks old and whose crying apparently didn’t bother Hoyt the same way: “I love her, and she shouldn’t be here. The system sucks.”

Waneta Hoyt would seem to agree. In the cavernous Tioga County courthouse last month, she told the court in a barely audible voice, “God forgive all of you who done this to me.” Judge Sgueglia was not so inclined. He stared at her for a time, then handed down his sentence. “I only have one thing to say to you,” he advised, “and that is to consider your sixth child. Whatever you tell this court, your husband, your God, you owe it to that boy to tell him the truth.” With that, four deputies escorted Hoyt from the courtroom, and her only surviving child bowed his head and wept.

credit murderpedia / Cynthia Sanz