Jeffrey Mailhot | Serial Killer

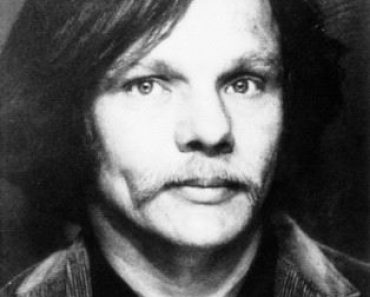

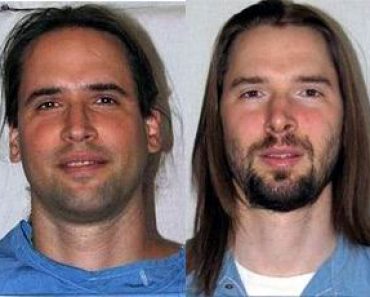

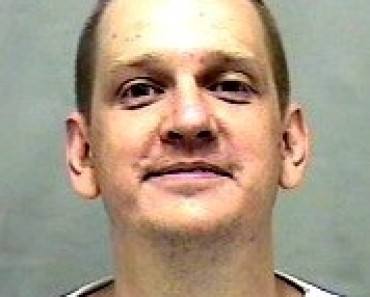

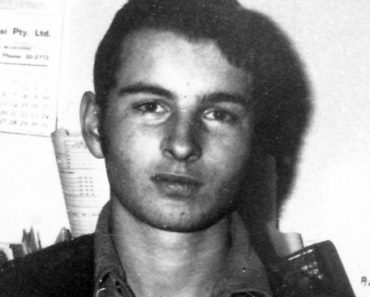

Jeffrey Mailhot

Born: 11-09-1970

Rhode Island Killer

American Serial Killer

Crime Spree: 2003-2004

Incarcerated at the Adult Correctional Institutions in Cranston, Rhode Island

Anyone traveling down Woonsocket’s Arnold Street in the afternoon or evening will likely see a few hard-looking women making eye contact with passersby, each hoping a lonely guy will stop to help her collect the freight for one more toke on the pipe. Occasionally a deal is struck, and, seeming oblivious to the risk, a woman rides off with a stranger.

Jeffrey Mailhot had stopped along the ramshackle strip of tenements and bar rooms more than a few times. The thirty-three-year-old machinist would usually invite his pay-for-play dates to his bachelor apartment, just around the corner on nearby Cato Street. As with so many things in his life, the pick-ups were something he kept strictly to himself.

But no secret stays secret forever. On July 16, 2004, Jeffrey Mailhot returned home from work and found officers waiting to arrest him. Soon he was seated in a small room at the Woonsocket Police Station and detectives were lobbing questions his way.

Jeffrey Mailhot

“Ever picked up a prostitute?” Detective Sergeant Edward Lee asked.

“I’ve seen ’em around,” Mailhot said, “but I haven’t picked any up…. I mean, I picked up a girl I thought I’d seen before. I thought she needed a ride, but then she propositioned me, so I let her out.”

His interrogators knew otherwise. Mailhot was in custody on a warrant charging him with assault with a dangerous weapon — in this case, his hands — and the complainants were two women he’d met on Arnold Street. Their stories were remarkably similar. Each told how she’d gone to his place expecting drinks and relaxation, but instead found herself squeezed in a choke hold and gasping for air. Each time the attack ended with him releasing his grip and telling his victim to leave.

The detectives had also pulled several pictures from the missing persons files, showing three women who had once been familiar faces on the street. If Jeffrey Mailhot liked playing rough with hookers, they reasoned, maybe he could explain a disappearance or two. After all, it would be very easy for his game to take a wrong turn.

Lee gave Mailhot a hard look.

“This is serious stuff,” he said, “so try to be as truthful as possible. If you picked up a prostitute, you picked up a prostitute. If you’re embarrassed, we don’t really care. We’re trying to get to the bottom of something. But if we start out like this, where it appears you’re not telling the truth, it doesn’t look good for you.”

Jeffrey Mailhot

“It goes downhill from there,” Detective Sergeant Steve Nowak added.

Jeffrey Mailhot responded with a nod.

“Ever pick up a prostitute?” Lee asked again.

“Yes.”

The questioning continued for another half hour. Then Lee opened a file folder and spread the pictures he’d gathered earlier across the table. There was Audrey Harris, missing sixteen months; Christine Dumont, gone almost two months; and Stacie Goulet, whose disappearance had been reported twelve days earlier.

Mailhot looked jolted. “I don’t know any of these girls,” he said.

“How are you so damn sure?”

“Because I never killed anybody. That’s what you’re getting at.”

“I don’t know if anyone in these pictures was killed,” Lee told him, “but they are missing.”

It was a eureka moment. The detectives knew they’d struck a nerve. Earlier in the interview, Mailhot had revealed that both his parents had died of cancer by the time he was twenty-two. Nowak seized on that.

“You know they had proper burials, that they’re in consecrated ground,” he said. “The families of these girls can’t mourn and say goodbye. They’ll have to live with that the rest of their lives — or until we get to the bottom of this.”

The only answer was a downcast look.

Jeffrey Mailhot

Lee spread out the pictures again. “What happened, Jeff?” he continued asking. “What happened? You just pushed it too far? Things got out of hand?”

Mailhot’s reply was barely audible. “Yeah,” he said with nod.

“What happened?”

“It went too far.”

They melt into the world like average nobodies, their dark secrets hidden by a mask of normalcy. They go to work, pay their bills, maybe relax with a beer now and then. They have friends who think they know them, but the only folks who really do are dead.

According to some experts, thirty to fifty serial killers may be prowling the United States at any one time.

Jeff Mailhot, one of the few to make Rhode Island his stalking ground, is nowhere near the top of the body count list. He dispatched three women with his choke hold; perhaps a dozen more narrowly escaped. By contrast, some serial killers have claimed responsibility for a score or more murders. Ted Bundy, for example, confessed to more than thirty, and Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer of Washington state, pleaded guilty to forty-eight.

Jeffrey Mailhot

Nevertheless, Jeffrey Mailhot stands out as a textbook example of such a monster.

Criminologists have sketched a demographic profile, and he fits it to a T. The typical serial killer is a white male who first takes up homicide around age thirty. The majority target strangers or near-strangers exclusively. Though a few travel about, leaving bodies here and there, most operate within a specific locale.

Beyond that, Mailhot displayed a predator’s psyche. He killed not for money or vengeance, but for the thrill of it. He snuffed out lives with his hands (never a knife or gun) to savor every moment of his victims’ suffering and fear. He preyed on a specific group — prostitutes — whom he’d come to regard as less than human. And he concealed his horrifying depravity with an unremarkable, everyday routine: He could dismember a body, toss the parts in a dumpster, and stop for a Bud on his way home.

Today Jeffrey Mailhot is behind bars at the Adult Correctional Institutions in Cranston, and he’ll likely remain there the rest of his life. When folks in Woonsocket talk about him, they still use words like “quiet” or “nerdy” or even “nice.” Then they ask, how could he do that? The police case may be closed, but the real mystery remains unsolved.

Some possible answers turn up. You might hear them in the gossip passed around a Main Street lunch counter, or read them in a sociologist’s reports. And in his rambling confession (captured on six hours of videotape) Jeffrey Mailhot offers some himself.

Jeffrey Mailhot

Nothing sums up Jeff Mailhot’s social thumbprint better than the image he left behind in his 1989 Woonsocket High School yearbook — which is to say, none. There’s a blank spot where his photograph should be, with the words “camera shy” beside his name.

Even after the big headlines, most Woon-socket residents could remember little about him. In the days following his arrest, reporters scoured the city for details of his background, badgering co-workers, high school chums, and even prostitutes on the Arnold Street strip. Many seemed to know him, yet knew little about him.

“I’d see him at parties or in bars, always toward the back of the room, never out mingling,” recalls John DiChristofero, a former classmate. “That’s the memory most people would have of him.”

On Grandview Avenue, the leafy-green subdivision where Jeffrey Mailhot grew up, former neighbors could describe him only as a kid who kept to himself. A few thought they knew the reason: trauma and tragedy had filled his early years. He was nine years old when his parents divorced, seventeen when his mother died of lung cancer, and twenty-two when his father succumbed to the same disease.

If he barely cast a shadow in the city he called home, it was not for lack of trying. As he moved into adulthood, Mailhot strived to shake off the anonymity of his teen years. He swaggered about like a tormented Walter Mitty, trying on various macho identities. He bought a Harley Davidson and a leather jacket and tried to fit in with the crowd of weekend outlaw bikers. He cheered TV wrestling and took up weight training to build a physique like that of the tough guys in the ring. On karaoke nights at Box Seats, a local sports bar, he’d grab the mike and shout heavy metal anthems by Metallica or Kiss. “I wanna rock ’n’ roll all night…”

Jeffrey Mailhot

Yet no matter how loud he screamed, few noticed. “He really didn’t stand out in a crowd,” says a manager at Box Seats. “Bad or good, he never stood out.”

His attempted metamorphosis may have flopped, but somewhere deep inside him, changes of another sort were happening. After several years at his stepmother’s Lincoln home, he went looking for a place of his own. He ended up back in Woonsocket, at 221 Cato Street. There were four units in the aging Greek Revival house, but two were vacant, apparently awaiting renovations. For a time an elderly woman occupied the apartment across the hall. Then she died, and no new tenant moved in.

That left Jeffrey Mailhot in the building alone. He’d found a perfectly private cocoon. He did have a small circle of friends, who saw him as something other than a misfit or introvert. They remember a sensitive soul — generous, good-humored, sometimes even gregarious.

“The Jeff I knew was never quiet,” says a Woonsocket woman who dated him off and on. “He was always laughing. And no matter what someone needed, he couldn’t say no. Up to the day of his arrest, I could say nothing bad about him.”

Nor was he the guy in the corner nursing the same drink all night, as some Woonsocket bartenders have maintained. She recalls him sitting by a campfire and sucking down beer until his head was nodding and his words became mumbles. On those nights his friends took his keys and found him a place to crash.

Jeffrey Mailhot

Even through the good times, though, she knew something was wrong. Jeffrey Mailhot, she says, was more than a neat freak. She suspected an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Every item in his home, his car and even his pockets had to be in the right spot. He constantly checked his wallet to be sure every bill faced the same way, with the stack always a quarter inch above the leather. Visitors to his apartment were afraid to touch things, especially his carefully sorted CDs and DVDs. If they did, they knew he’d be on his feet a moment later, trying to look casual as he anxiously saw to it that everything was in its place.

Then there were his dark moods. She and other friends took note of the spare house key he hid outside his door, so they could get inside to check on him if need be. “Sometimes he wouldn’t answer the phone or come to the door for days,” she recalls. “It was like he dropped off the earth.”

One evening she confided she was falling for him, and was floored by his response: “He told me, ‘I’m sorry, I can never be in love with anyone. I’ll always be alone.’ ”

The emotional swings grew more intense in the months before his arrest. She remembers a night they were laughing out loud at a comedy video; a moment later tears were rolling down his face. “I asked him what was wrong,” she says, “and he told me, ‘I think I should be alone for the rest of my life.’ ”

Despite his quirks and the shock and pain that came following his arrest, she has fond memories of the relationship. She talks of sitting behind him on his motorcycle, riding for miles until they spied some little place with a pool table. He called her Butterfly; she called him Bear.

Jeffrey Mailhot

She felt secure enough with him to introduce some risky business during sex. In passionate moments she would allow him to grasp her neck until breathing became a struggle. Then he’d let go, and she’d gulp some air.

“We both enjoyed it,” she says. “I remember telling him, my God, you look so psychotic when you do that.”

From time to time, as far back as the early ’90s, Woonsocket police had speculated that a serial killer could be preying on the city’s prostitutes, who seemed to disappear with a grim sort of clockwork. In the summer of 2004, with three women gone in seventeen months, the notion was once again making the rounds. “Just because there was nothing,” Nowak recalls. “They just disappeared. We had no clues. No suspects. They just kind of vanished. So it was always in the back of your mind.”

But Nowak and Lee were not entirely convinced. In the past, police had always been able to pin down the sporadic deaths as isolated cases. Often the streetwalkers were victims of their own high-risk lifestyles. Probably, it would turn out the same with Harris, Dumont and Goulet.

The break came in mid-July, with a tipster’s call to police headquarters. He suggested detectives contact Jocelyn Martel, a local woman with an arrest record for drug offenses and prostitution. They found her at a detention center, awaiting trial.

Jeffrey Mailhot

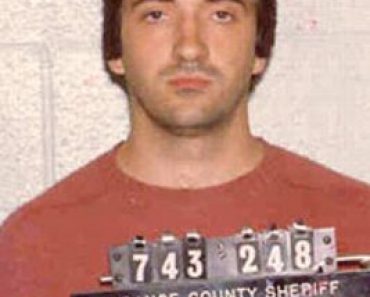

Martel told of a harrowing encounter with a man who offered cash for sex, and then attacked her inside his apartment. Her description of the building and its location matched 221 Cato Street. The detectives got Mailhot’s name from utility bills, and his picture from the DMV. They showed her a photo spread, and she picked him out as her assailant.

In the days that followed cops tracked down several more women who described similar assaults. One joined Martel in signing a complaint. That was enough to get an arrest warrant.

But their first encounter with Jeffrey Mailhot knocked Lee and Nowak off balance. He seemed more milquetoast than multiple-murderer. He was polite, friendly, soft-spoken. His police record was clean. His landlord called him the ideal tenant, a guy with a steady job who always had the rent check. Though weightlifting had packed some muscle onto his five-foot-three-inch frame, his fair complexion and cheeky face gave him a Campbell Soup Kid look.

“He had the whole Jekyll-and-Hyde thing going,” Lee remembers. “Everybody he worked with loved him. The landlord, he’s yelling we should leave the kid alone. We thought, maybe he had something to do with one of them, maybe two of them, but no way is this guy a serial killer.”

Then Jeffrey Mailhot buried his brush-cut head in his hands and began to talk.

Jeffrey Mailhot

“I just want to be totally honest,” he said. “I don’t want to hide any more. I don’t want this shit inside me anymore. I want to do what I have to, to help the situation, any way I can, and I want that to be my last act. I’m not expecting forgiveness.”

As the minutes ticked by in the spare interrogation room, Jeffrey Mailhot recounted his adventures in Woonsocket’s night town. Over the years, he said, he’d picked up perhaps thirty prostitutes. Most trysts took place at his apartment, where privacy was guaranteed. He couldn’t recall exactly how many women he’d throttled, but he guessed ten or twelve had survived and escaped. Mailhot’s words picked up speed as he recalled the attacks. At one point he rose to his feet to demonstrate his squeeze technique. He held his left arm in front of his chest, as if grasping a victim, and gripped his wrist with his right hand. “I lean back,” he said, “so it puts more pressure on their neck.” With minimal prodding, he provided details on several chokings. On two occasions his victims fell to the floor unconscious; both were back up in minutes, and neither wasted time getting out the door. Another who got away stood outside shouting that she had a cell phone and she’d dialed 911; the cops never showed. One woman convinced him to back off by playing the submissive slave. “She’s standing in the bedroom saying, please, master, please let me go,” he recalled. “I think she offered my money back.” “Any of these girls fight back? Any of them cut you or anything?” Lee asked. “A couple of scratch marks,” Mailhot replied. “One of them, she gouged my eye to get away.”

Jeffrey Mailhot

Things finally spun out of control the night he picked up Audrey Harris. He was driving home after too much beer at the K2U strip club when he spied her on a sidewalk. He pulled up beside her and suggested a quick trip to his place. She agreed.

“I was gonna have sex with her, just straight sex,” he told the detectives. “She got undressed, I got undressed…I went to get her the money, she turned around, and that’s when I went up behind her and started choking….She was kicking, scratching, trying to get away. As she was losing her breath she stopped struggling. Then I let her go. I looked at her — her eyes were open, but she wasn’t looking at anything. I figured she was dying. That’s when I got the pillow. I suffocated her.” “So it wasn’t accidental,” Lee said. Jeffrey Mailhot insisted it was. “I didn’t want to do that,” he said. “But once I realized what was happening, I was scared to death. I had to finish it.”

By his own account his actions left him stunned for several minutes. Then he shook off his disbelief, dragged the body to the bathroom, and stumbled to his bed for a night of drunken slumber. The next morning he wandered to the toilet and was startled to see a corpse in the tub. The previous night’s events rushed back into his head. He called his employer to say he needed a day off. That evening he wrapped the body in a cheap rug and loaded it into his SUV. He drove about the city, searching for a place to dump his cargo, and then returned home, convinced it was too risky.

For two days the body lay in his apartment while he pondered how to make it go away. Then, like an episode from “The Sopranos,” he used a newly purchased handsaw to dismember it in the bathtub. An aerosol spray helped mask the smell, and a few drinks steadied his nerves.

Jeffrey Mailhot

The parts went into trash bags, and the bags into various commercial dumpsters. No one would notice the small bags, he reasoned, and he was right. He made the drop offs under cover of night, but early enough to allow himself another stop at the K2U before bedtime. Mailhot picked up Christine Dumont some fourteen months later, and Stacie Goulet two months after that. Both women died in his apartment. Again, the bodies were dismembered and disposed of in trash containers. He no longer told himself the deaths were accidents. “Just an urge,” he said. “What are you thinking about when you’re driving around to get a prostitute?” Lee asked. “Sex or choking?” “Sex,” Mailhot replied. “What’s the biggest rush?” “I’d say maybe the actual getting them into my place.” “The door shuts, and …?” “You could say it like that.”

For nearly six hours the two detectives listened while a butcher described his deeds. Since that night they’ve looked back on the episode many times, and not surprisingly, they have their own ideas as to why Jeffrey Mailhot killed. “For him, it was all a fantasy,” Lee says. “He’d slip into this fantasy to escape his depressive world. And once he’s taken that final step, once he kills, he’s like an alcoholic. He’s had a taste, he’s addicted, and no way is he going to stop.”

It’s a bulls-eye analysis, experts say. Criminologists and psychologists have described the typical serial killer as a frustrated guy who dreams of being at the top in the pack. He stalks his victims to satisfy that desire.

“There is a thrill and tremendous power to killing, whether anyone admits it or not,” says Ronald M. Stewart, a forensic psychiatrist from Providence who has testified at numerous criminal trials.

Jeffrey Mailhot

“When someone doesn’t have much control over their own life, they might seek gratification this way. They become predators. They seek out targets of opportunity. Prostitutes are frequent victims because they’re just that — isolated, desperate people out on the streets.”

The alpha-dog-wannabee theory is endorsed by Jack Levin and James Alan Fox, criminology professors at Boston’s Northeastern University. In their book Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder, they ascribe such a killer’s motivation to a need for power.

“One common trait among serial killers is that they’re losers,” Fox says. “If Jeffrey Dahmer had learned to bounce a basketball, maybe he could have been the popular kid, maybe he would not have killed seventeen people.”

“Killing is his way of feeling special,” adds Levin. “In a way he’s playing God.”

Jeffrey Mailhot

In that context, Mailhot’s fantasies about motorcycle rebels and TV wrestlers become something more than comical trappings of arrested male development.

“He was trying to replace his inadequacies with identities that imply power and control,” Stewart says. “That’s probably what he was trying to achieve the whole time.”

Many serial killers are sociopaths, the psychiatric term for a person with no capacity for empathy and no conscience whatsoever. But that label doesn’t fit every case, according to Levin and Fox. Some killers, they argue, neutralize their feelings of guilt by dividing people into two groups; those they care about, and those they victimize. And that may explain why Jeffrey Mailhot and others confess and express remorse when caught.

“They prey on people whom they’re able to dehumanize or devalue, maybe prostitutes, or the homeless,” Fox says. “They see their victims as less worthy, just as Nazi doctors were able to experiment on Ausch-witz inmates by dismissing them as vermin.”

“As long as he’s alone he can hold onto these wrongheaded notions that he’s ridding the streets of filth,” Levin adds. “But once he’s apprehended and he gets some feedback, the fantasy bursts and he realizes he’s done despicable things.” Some psychologists believe the killer’s need for dominance springs from chaotic events during childhood, such as abandonment or extreme abuse. Levin suspects that holds true for Mailhot. While his parents may have been kind and loving, their divorce and early deaths could have left him feeling lost and adrift. “We’re talking about frustration, catastrophic losses in this guy’s life,” he says. “I think that’s a key to understanding this.”

Throughout his confession, Jeffrey Mailhot himself tried to explain his motives, and his words jibe with the researchers’ theories.

Jeffrey Mailhot

He dismissed his victims with contempt and disgust. “Maybe I was doing them a favor,” he said, “because they were just killing themselves anyway…. They were just going down the toilet.”

He described his existence as purposeless, his world as dark and ugly. “It’s stupid for me to be saying this,” he said with a dry chuckle, “but with all the killings and all the bad and all the drugs, the world is someplace I don’t want to be…I know I’m not doing anything special with my life. I mean, I’d like to have a million dollars and do all kinds of things, but I don’t have the motivation.”

Lee and Nowak asked if he’d kill again if had the chance. “I probably would,” he said. “I probably would.”

A confession alone is no guarantee of a conviction; after all, a good defense lawyer will make every effort to discredit any incriminating statements. With that in mind, police quickly launched an exhaustive search for physical evidence.

Even before Mailhot concluded his grim account, officers from the Woonsocket Police crime scene unit were searching 221 Cato Street. At first glance they saw a typical bachelor pad, three small rooms furnished with mismatched hand-me-downs and all the latest electronic gadgetry. Before long, though, they uncovered signs of the slaughter as they darkened the bathroom, and then sprayed the tub, floor and walls with an aerosol can of Luminol. Every fan of “CSI” or “Crossing Jordan” knows the procedure: the chemical reacts with the iron in blood by producing a blue-green glow, and tiny traces that would otherwise escape the naked eye shine and become visible.

The bathroom light went off —and the investigators gasped. The porous grout lines between the tiles became a luminescent grid, revealing the gore Jeffrey Mailhot had tried to scrub away.

Jeffrey Mailhot

Out came the tub, out came the toilet, then floorboards, pipes, and sections of tiled wall. By the time the officers finished their work, all that remained of the bathroom was a hole gaping to the basement below. Every item and chunk of debris — carefully packaged and labeled — was headed to a state lab for forensic scrutiny.

The hunt for evidence didn’t stop there. The mop Mailhot used to clean the floor proved to be another trove of blood evidence. Investigators seized his home computer, too, to determine if he’d ever discussed his crimes on Internet sites. (He hadn’t.) They also grabbed a Halloween party snapshot; it showed their suspect dressed as a TV wrestler and choking a teddy bear.

In the basement, officers found a handsaw that matched Mailhot’s description of the ones he used to cut up the bodies. The officers then reviewed tapes from a surveillance camera at a local hardware store, and discovered footage of the suspect buying the tool just a day after the last victim’s disappearance.

From there the search moved to the street. Jeffrey Mailhot had told Lee and Nowak he’d disposed of a latex glove and some small body pieces by flushing them down the toilet. With that in mind, investigators launched a probe of the sewer line outside his building. They first explored the pipe using a small video camera attached to long cable. What they found was an infestation of tiny worms apparently attracted by high-protein material coming down the drain.

Jeffrey Mailhot

A public works crew then dug up several feet of the sewer line. For all that effort, the pipe proved to be a dead end. The lab team determined Mailhot’s diet had provided a feast for the worms; he’d been sucking down protein shakes to help him bulk up at the gym.

At the same time some two dozen local and state officers were scouring the Central Landfill in Johnston. Armed with garden rakes and dressed in protective coveralls, they combed through tons of rotting garbage, a stinking, sweaty task in the July heat.

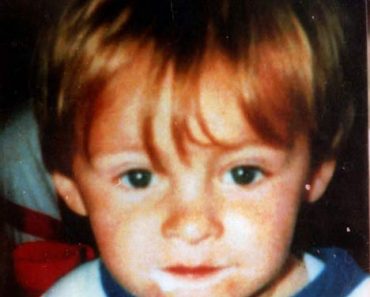

Twelve days after Mailhot’s arrest an officer-in-training tore open a plastic trash bag and found human body parts inside. The state medical examiner collected DNA material and compared it with samples from relatives of the three missing women. The procedure produced a match, and investigators were able to tell Stacie Goulet’s parents that they had found the remains of their twenty-five-year-old daughter.

While the landfill search turned up nothing of Harris or Dumont, similar DNA tests on the blood evidence from the apartment corroborated Mailhot’s confession.

By the end of their investigation, police had gathered more than 170 items of evidence. Not one piece was ever presented in court, however, as the defendant decided to forgo a trial. On February 15 of last year in Providence Superior Court, a teary-eyed Jeffrey Mailhot pleaded guilty to three counts of murder and two of assault. The judge sentenced him to two life terms plus ten years. He should be eligible for parole by age seventy-seven.

Jeffrey Mailhot

He made no plea for mercy. “Nothing I can do can take away the pain,” he told the court. “I hope God can give the families — both the victims’ and my own — some peace.”

Since Mailhot’s arrest, a few things have changed in Woonsocket, but not much. The cops who prompted him to confess have received promotions: Lee is now captain of detectives, and Nowak, a lieutenant. Buddy’s Cafe, an Arnold Street hangout some saw as a prostitute magnet, closed its doors after forty-eight years. The hookers and johns, however, have yet to retreat from the area.

The relatives of Mailhot’s victims continue to struggle with his painful legacy. ”I still get nauseous when I see garbage trucks,” says Steve Krieg, Goulet’s ex-husband and the father of her two children. “I try to not ride behind them.”

As for Jeffrey Mailhot, he’s adjusted to prison life, at least according to the letters he sends his ex-girlfriend. “He sounds upbeat,” she says. “I wrote back and asked, did you ever feel that way — that rage — with me? He said never.”

source: murderpedia / John Larrabee and Russ Olivo