Gameel Al-Batouti | Revenge Murder

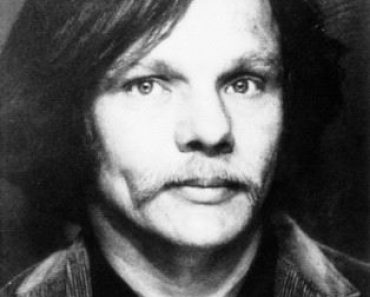

Gameel Al Batouti

Egypt Air Flight 990

Mass Murderer

Crime Spree: October 31, 1999

EgyptAir Flight 990 was a regularly-scheduled Los Angeles-New York-Cairo flight. On October 31, 1999, at around 1:50 a.m. EST, Flight 990 dived into the Atlantic Ocean, about 60 miles south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, in international waters, killing all 217 people on board.

Flight Details

Flight 990 was being flown in a Boeing 767-366ER aircraft with the registration SU-GAP, named Tuthmosis III after a pharaoh from the 18th Dynasty. The flight was carrying 14 crew members and 203 passengers from seven countries (Canada, Egypt, Germany, Sudan, Syria, United States, and Zimbabwe).

Included in the passenger manifest were over 30 Egyptian military officers; among them were two brigadier-generals, a colonel, major, and four other air force officers. Newspapers in Cairo were prevented by censors from reporting the officers’ presence on the flight.

Flight 990 was crewed by 14 people, 10 flight attendants, and four flight crew members. Because of the scheduled flight time, the flight required two complete flight crews (each consisting of one captain and one first officer). EgyptAir designated one crew as the “active crew” and the other as the “cruise crew” (sometimes also referred to as the “relief crew”).

It was customary for the active crew to make the takeoff and fly the first four to five hours of the flight. The cruise crew then assumed control of the aircraft until about one to two hours prior to landing, at which point the active crew returned to the cockpit and assumed control of the airplane.

EgyptAir designated the captain of the active crew as the Pilot-in-Command or the Commander of the flight. The active crew consisted of Captain Mahmoud El Habashy and First Officer Adel Anwar, and the cruise crew were Captain Amal El Sayed and First Officer Gameel Al-Batouti (the NTSB reports use the spelling “El Batouty”).

ATC Tracking

U.S. Air Traffic Controllers provide transatlantic flight control operations as a part of the “New York Center” (referred to in radio conversations simply as “Center” and abbreviated in the reports as “ZNY”). The airspace is divided into “areas,” and “Area F” was the section that oversaw the airspace through which Flight 990 was flying.

Transatlantic commercial air traffic travels via a system of routes called North Atlantic Tracks, and Flight 990 was the only aircraft at the time assigned to fly North Atlantic Track Zulu. There are also a number of military operations areas over the Atlantic, called “Warning Areas,” which are also monitored by New York Center, but records show that these were inactive the night of the accident.

Interaction between ZNY and Flight 990 was completely routine. After takeoff, Flight 990 was handled by three different controllers as it climbed up in stages to its assigned cruising altitude.

The aircraft, like all commercial airliners, was equipped with a Mode C transponder, which automatically reported the plane’s altitude when queried by the ATC radar. At 1:44, the transponder indicated that Flight 990 had leveled off at FL330. Three minutes later, the controller requested that Flight 990 switch communications radio frequencies for better reception. A pilot on Flight 990 acknowledged on the new frequency. This was the last transmission ever received from Flight 990. Then the records of the radar returns then indicate a sharp descent.

The Decent Into The Ocean

In a span of 36 seconds, the plane dropped 14,600 feet (nearly three miles). Several subsequent “primary” returns (simple radar reflections without the encoded Mode C altitude information) were received by ATC, the last being at 0652:05. At 0654, the ATC controller tried notifying Flight 990 that radar contact had been lost, but received no reply.

Two minutes later, the controller contacted ARINC to determine if Flight 990 had switched to an oceanic frequency too early. ARINC attempted to contact Flight 990 on SELCAL, also with no response. The controller then contacted a nearby aircraft, Lufthansa Flight 499, asking it to see if it could raise Flight 990. The German carrier responded that it had no radio contact and was not receiving any ELT signals. Air France Flight 439 was asked to overfly the last known position of Flight 990, but reported nothing out of the ordinary. Center also provided coordinates of Flight 990’s last-known position to Coast Guard rescue aircraft.

The Crash of Flight 990

Flight data showed that the flight controls were used to move the elevators in order to initiate and sustain the steep dive. The flight deviated from its assigned altitude of 33,000 feet (FL330) and dove to 16,000 feet over 44 seconds, then climbed to 24,000 and began a final dive, hitting the Atlantic Ocean about two and a half minutes after leaving FL330.

Radar and radio contact was lost 30 minutes after the aircraft departed JFK Airport in New York on its flight to Cairo. The cockpit voice recorder recorded the First Officer (Gameel Al-Batouti) repeating “I rely on God” eleven times while the Captain asked repeatedly “What is this?” during the dive. There were no other aircraft in the area. There was no indication that an explosion occurred on board. The engines operated normally for the entire flight until they shut down and the left engine was torn from the wing from the stress of the maneuvers.

Search and Rescue Efforts

Search and rescue operations were launched within minutes of the loss of radar contact, with the bulk of the operation being conducted by the United States Coast Guard (USCG). At 3:00 AM, an HU-25 Falcon jet took off from Airbase Cape Cod Mass, becoming the first rescue party to reach the last known position of the plane. All USCG cutters in the area were immediately diverted to search for the aircraft, and an urgent marine information broadcast was issued, requesting mariners in the area to keep a lookout for the downed aircraft.

At sunrise, the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy training vessel King’s Pointer found an oil sheen and some small pieces of debris. Rescue efforts continued by air and by sea, with a group of USCG cutters covering 10,000 square miles on October 31 with the hope of locating survivors, although all that could be recovered was a single body in the debris field.

Atlantic Strike Team members brought two truckloads of equipment from Fort Dix to Newport to set up an incident command post. Officials from the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were dispatched to join the command. The search and rescue operation was eventually suspended on November 1, 1999, with the rescue vessels and aircraft moving instead to recovery operations.

These operations were ceased when the naval vessels USS Grapple and USNS Mohawk and the NOAA research vessel Whiting arrived to take over salvage efforts, including recovery of the bulk of the wreckage from the seabed.

In total, a C-130, an H-60 helicopter, the HU-25 Falcon and the cutters USCGC Monomoy, USCGC Spencer, USCG Reliance, USCG Bainbridge Island, USCG Juniper, USCG Point Highland USCG Chinook, and USCG Hammerhead, along with their supporting helicopters, participated in the search.

A second salvage effort was made in March 2000 that recovered the aircraft’s second engine and some of the cockpit controls.

The Investigation

Under the International Civil Aviation Organization treaty, the investigation of an airplane crash in international waters is under the jurisdiction of the country of registry of the aircraft. At the request of the Egyptian government, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) took the lead in this investigation, with the Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority (ECAA) participating.

The investigation was supported by the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the United States Coast Guard, the U.S. Department of Defense, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Boeing Commercial Airplanes, EgyptAir, and Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Engines.

Two weeks after the crash, the NTSB proposed declaring the crash a criminal event and handing the investigation over to the FBI. Egyptian government officials protested, and Omar Suleiman, head of Egyptian intelligence, traveled to Washington to join the investigation.

Hamdi Hanafi Taha Defection

In February 2000, EgyptAir 767 captain Hamdi Hanafi Taha sought political asylum in London after landing his aircraft there. In his statement to British authorities, he claimed to have knowledge of the circumstances behind the crash of Flight 990. He is reported to have said that he wanted to “stop all lies about the disaster,” and to put much of the blame on EgyptAir management.

Reaction was swift, with the NTSB and FBI sending officials to interview Taha, and Osama El-Baz, an advisor to Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, saying, “This pilot can’t know anything about the plane, the chances that he has any information [about the crash of Flight 990] are very slim.”

EgyptAir officials also immediately dismissed Taha’s claim. Taha’s information was reportedly of little use to the investigators, and his application for asylum was turned down.

Investigation Conclusions

NTSB

The NTSB’s final report was issued on March 21, 2002, after a two-year investigation. Their conclusion was:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the EgyptAir flight 990 accident is the airplane’s departure from normal cruise flight and subsequent impact with the Atlantic Ocean as a result of the relief first officer’s (Gameel Al-Batouti) flight control inputs. The reason for the relief first officer’s (Gameel Al-Batouti) actions was not determined.

ECAA

The ECAA’s final report, based largely on the NTSB’s, came to distinctly different conclusions:

1. Gameel Al-Batouti, the Relief First Officer (RFO) did not deliberately dive the airplane into the ocean. Nowhere in the 1,665 pages of the NTSB’s docket or in the 18 months of investigative effort is there any evidence to support the so called “deliberate act theory.” In fact, the record contains specific evidence refuting such a theory, including an expert evaluation by Dr. Adel Fouad, a highly experienced psychiatrist.

2. There is evidence pointing to a mechanical defect in the elevator control system of the accident. The best evidence of this is the shearing of certain rivets in two of the right elevator bellcranks and the shearing of an internal pin in a power control actuator (PCA) that was attached to the right elevator. Although this evidence, combined with certain data from the Flight Data Recorder (FDR), points to a mechanical cause for the accident, reaching a definitive conclusion at this point is not possible because of the complexity of the elevator system, the lack of reliable data from Boeing, and the limitations of the simulation and ground tests conducted after the accident. Additional evidence of relevant Boeing 767 elevator malfunctions in incidents involving Aero Mexico (February 2000), Gulf Air, and American Airlines (March, 2001). There were also two incidents on a United Airlines airplane in 1994 and 1996.

3. Investigators cannot rule out the possibility that Gameel Al-Batouti may have taken emergency action to avoid a collision with an unknown object. Although plausible, this theory cannot be tested because the United States has refused to release certain radar calibration and test data that are necessary to evaluate various unidentified radar returns in the vicinity of Flight 990.

Source: murderpedia | wikipedia | the guardian.com | britannica.com

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links