Arthur Bishop | Utah’s Child-Killer

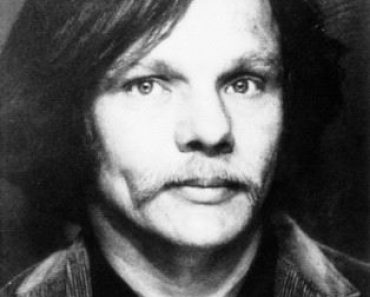

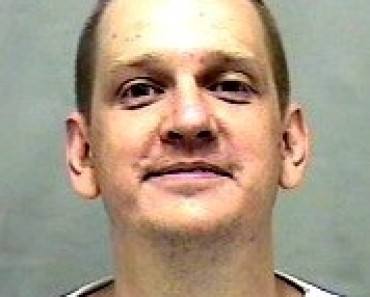

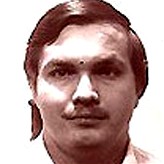

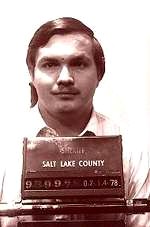

Arthur Gary Bishop

Born: 09-29-1952

Utah’s Child-Killer

American Serial Killer

Crime Spree: 1979 – 1983

Death: Executed by Letha; Injection on 07-10-1988

Hinckley, Utah, is a tiny desert town with less than 700 residents. It lies 100 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, in bone-dry Millard County, where tourists are scarce and locals scratch their living from the sun baked soil. The landscape breeds hard men and women, scorpions and rattlesnakes.

And, in 1951, without warning, it gave birth to a monster.

Long after the fact, defense attorneys would describe Arthur Bishop as “a lonely, frightened child,” but nothing in the public record validates that claim. In fact, he seemed to be a model son, and even in extremist never raised the specter of abuse. Reared by devout Mormon parents in the ways of their faith, Arthur Bishop was an honor student and a proud Eagle Scout.

Arthur Bishop

Such jibes aside, younger brother Douglas Bishop, born in 1956, appeared to idolize his only sibling. Nearly three decades would pass before a stunned community learned how much the Bishop brothers really had in common, and even then no probing questions would be asked.

In 1969, after graduation from high school, Arthur followed the tenets of his church by serving as a teenage missionary in the Philippines. With that service completed, he came home and enrolled at Stevens-Henager College, a Utah business school. He completed the school’s accounting course with top-notch grades.

A Darker Side

There was a darker side to Arthur Bishop, slowly revealed by degrees, that would never be guessed from his transcripts, early work experience, or conversations with his family and friends. The nearly perfect son would later say he was addicted to pornography, and more specifically to “kiddy” porn. Where most viewers would have been revolted, Arthur Bishop was enthralled. He nurtured fantasies, elaborating on them over time, until the fantasies alone were no longer enough to pacify him.

From Morbid Daydreams

No one can say with any certainty when Arthur Bishop crossed the line from morbid daydreams into active pedophilia. Years later, scores of Utah parents would complain of Bishop molesting their children, but none came forward at the time, not even as fantasies degenerated into murder. They were silent, some perhaps warning their children to avoid the stranger’s company, none reaching out to the police while it might still have done some good.

Bishop’s first brush with the law had nothing to do with children or sex. In February of 1978 he was accused of embezzling $8,714 from a used-car dealership where he had worked as a bookkeeper since July 1977. His friends and family were stunned, but Arthur Bishop seemed prepared to take his medicine. He pleaded guilty as charged, receiving a five-year suspended jail sentence in return for a promise of full restitution. His repentance seemed sincere.

Until he dropped out of sight.

Arthur Bishop was on the lam, an unlikely fugitive who would spend the next five years living under pseudonyms, finding work where he could, stealing money when it suited him. The arrest warrant issued for his probation violation would never be served.

The next time Arthur Bishop went to jail, it would be for murder, and he would be Utah’s most notorious killer of the twentieth century.

Big Brother

Arthur Bishop did not run far when he went into hiding. A simple name change was enough to throw police off his track, and Bishop remained in Salt Lake City, reborn as “Roger W. Downs.” He used that name to join the Big Brother program, thereby placing himself in close proximity to boys craving a sympathetic father figure.

Author Clifford Linedecker, in his book Thrill Killers, reports that spokesmen for the Big Brother/Big Sister organization later admitted receiving tips that “Downs” had molested at least two children while enrolled with their program, but neither was his assigned “little brother.” The accusations were allegedly reported to police, who took no action.

The Mormon Church excommunicated Bishop in October 1978, but if he even knew it, the official shunning had no visible effect on Bishop’s life. He worked odd jobs, indulged himself with boys whenever possible, and fought the secret urges that demanded more than sex.

A year after his excommunication from the church, Arthur Bishop lost that struggle and surrendered to the darkness festering within.

Four-year-old Alonzo Daniels was playing in the courtyard of his Salt Lake City apartment complex on October 14, 1979, when he vanished without a trace. His worried mother summoned relatives to search the complex and surrounding streets, to no avail. Police were summoned, going door-to-door. They met neighbor Roger Downs almost immediately, in his flat across the hall from Alonzo’s apartment, but their questions were routine and Downs denied any knowledge of the boy’s whereabouts.

Already Gone

Officers had no way of knowing that Alonzo was already dead when they reached the apartment complex. Arthur Bishop had lured him from the courtyard with a promise of candy, attempting to undress and fondle Alonzo in his living room. He panicked when the boy began to cry, sobbing threats to tell his mother what had happened.

Bishop clubbed the child with a hammer, but it failed to stop Alonzo’s wailing. Finally, Bishop carried him into the bathroom and drowned him in the tub. Afterward, he stuffed the corpse into a large cardboard box and carried it out to his car, past Alonzo’s mother as she paced the courtyard, calling out her child’s name.

By late afternoon, Salt Lake County’s search and rescue team had joined the fruitless hunt for Alonzo Daniels. Hundreds of civilians pitched in over the next few days, including students and faculty from the University of Utah and members of a Teamsters Union local. Photos of Alonzo and descriptions of his clothing were printed and broadcast throughout the state. Police questioned hundreds of people, but none outside his family acknowledged seeing the boy.

By the night of October 14, the boy was already gone. Arthur Bishop drove the crated corpse to Cedar Fort, 20 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, and buried Daniels in the desert, his unmarked grave shaded by trees that gave the nearby town its name.

Returning home, Arthur Bishop felt a mixture of emotions. Revulsion at his crime vied with fear of arrest and perverse excitement. Dominating all other sensations was a certainty that he would kill again, unless he found some means by which to stop himself.

The Skater

In the year after he killed Alonzo Daniels, Arthur Bishop sought a less dangerous outlet for his deadly urges. Instead of children, he decided to kill puppies, adopting 15 or 20 from Salt Lake City animal shelters over the next 13 months, using them as surrogates for children. “It was so stimulating,” he later told Detective Don Bell (quoted in the Deseret News). “A puppy whines just like Alonzo did. I would get frustrated at the whining. I would hit them with hammers or drown them or strangle them.”

Bishop’s neighbors never seemed to notice, and if they had, cruelty to animals was a cut-rate misdemeanor, nothing to compare with kidnapping and murdering a child. Still, puppies only went so far toward satisfying Bishop’s urges. He continued to molest children sporadically, using charm or threats to prevent them from carrying tales. Only resistance or the threat of prison seemed to spark his killer instinct and push Bishop over the edge.

On Saturday, November 8, 1980, 11-year-old Kim Peterson met Arthur Bishop at a Salt Lake City roller-skating rink. They talked about skates, Kim mentioning that he would like to sell his and buy a new pair. Bishop feigned interest, telling Peterson he would pay $35 for the skates. It is unclear whether Bishop agreed to meet Kim on Sunday, or what name he used, but Peterson left home with the skates on November 9th, telling his parent he had found a buyer. No names were mentioned, but he promised to come straight home after the transaction was concluded. He never returned.

Arthur Bishop

Police were called to the Peterson home near sundown, when Kim failed to return in time for dinner. Another fruitless search began, including a canvass of skaters from the rink where Kim had met his presumed abductor on Saturday. Several witnesses recalled a youth of Peterson’s description, talking to a man aged 25 to 35, full-faced with glasses, wearing blue jeans and an army-style jacket or parka. Two of the witnesses agreed to be hypnotized, the session producing further details: dark hair and bushy eyebrows, weight around 200 pounds. One skater claimed the man had driven away in a silver Chevy Camaro with out-of-state license tags, perhaps from Nevada. All leads led nowhere.

Police saw no similarity to their suspect in “Roger Downs,” living in an apartment several blocks from Kim Peterson’s home. Again, they questioned him routinely, making no connection to the Daniels case. Nothing in the bland 29-year-old’s demeanor let them know that he had bludgeoned Kim Peterson to death and buried his corpse near Alonzo’s, outside Cedar Fort.

There was plenty of room in the desert, and murder was easier the second time around. Arthur Bishop still feared arrest, still spared his victims if they promised not to talk, but he was learning that murder provided a rush all its own. And Bishop began to urn for that rush

A Beautiful Boy

Eleven months passed before Arthur Bishop killed again. He was browsing through a local supermarket on October 20, 1981, when he spotted 4 year old Danny Davis. Bishop would later describe Danny as a ‘beautiful boy.’

Danny was fumbling with the market’s gumball machine, but couldn’t seem to get anything to come out. Bishop offered him candy, but the boy refused it. Bishop headed toward the exit and soon realized the boy was following him. He waited for Danny to catch up and led him into the parking lot.

Danny’s grandmother missed him when she finished her shopping. Suddenly alarmed, she called for the store’s manager. Employees and customers joined in a search, but they were already too late. Several shoppers recalled a boy at the gumball machine, assisted by a smiling young man, but they could not identify photos of Danny Davis. Hypnosis clarified the descriptions slightly, put positive IDs remained elusive. One report described a boy of Danny’s size and age leaving the market with two adults, a man and a woman. Again, the well meant leads led nowhere.

Arthur Bishop

Once again, as in the Daniels case, searchers fanned out through the nearby desert and mountains. Temperatures dropped into the thirties overnight, reminding police that Danny was last seen wearing only a T-shirt, blue jeans and sandals. When their quarry failed to turn up on the first day or the second, divers plumbed the depths of Big Cottonwood Creek, east of town. Sheriff’s deputies dragged ponds, searched roadside ditches, poked through garbage in a hundred alleys. All to no avail.

The hunt for Danny Davis rapidly became the most intensive search in Salt Lake County history. Fliers were printed with the missing boy’s photo, copies sent to law enforcement agencies throughout the U.S. A $20,000 reward for information brought no takers. Calls for help to the FBI, Child Find and the National Crime Information Center produced no useful leads.

“Roger Downs,” residing half a block from the market where Danny disappeared, had nothing to share with police when they knocked on his door. Again, the questions were routine. And again, no one realized that the same clueless neighbor had lived in close proximity to vanished victims Alonzo Daniels and Kim Peterson. Neighbors later recalled to police and the press that “Downs” had an unusual fondness for children. At the same time, however, he often played host to groups of “rowdy hippies” and scruffy-looking bikers, including one youth who liked to set fires until “Downs” punched him out and banished him from the house.

Arthur Bishop

All this, they remembered years later. Too late.

“Roger Downs” was not tempted by the public reward offer for information leading to Danny Davis. He had money to spare from his latest embezzlement scheme. Several weeks before the Davis kidnapping, bookkeeper “Lynn E. Jones” had gone to work at a Salt Lake City ski shop. When he failed to return from lunch one afternoon, the proprietor found $10,000 missing from the store, along with “Jones’s” personnel file.

By the time police visited his rented house to question Arthur Bishop, Danny Davis was already dead. After molesting Danny, Bishop had silenced the boy’s sobbing by manually pinching his nostrils and covering his mouth. The next day, Wednesday, Bishop made another trip to Cedar Fort, planting his third victim beside the other two.

Panic

Utah police might be helpless in the face of Bishop’s cunning, but state legislators were galvanized by the spate of disappearances. When three-year-old Rachel Runyan was kidnapped from a school playground in Sunset, 30 miles north of Salt Lake City, in August 1982, the public outcry was predictable. Discovery of her strangled corpse a short time later turned the fear to panic. Deafened by grass-roots calls for action, local politicians did what politicians always do: they passed another law.

First-degree murder was already a capital crime in Utah, but legislators showed their indignation with a new statute on child abduction, ranked among the strictest in the nation. Depending on the circumstances of a given kidnapping, convicted abductors faced mandatory 5-, 10- or 15-year prison terms for their crime. Civic groups applauded the effort, but it did nothing to help locate Utah’s child-killer.

Investigators soon dismissed any link between Rachel Runyan’s murder and the vanished boys of Salt Lake City. Statewide, they were deluged with reports of strangers accosting children on streets, in parks and playgrounds–but still, no one blew the whistle on child molester Arthur Bishop, alias “Roger Downs.” Rumors circulated of an occult motive in the crimes, but police dismissed those in turn, noting that none of the missing boys had been kidnapped within a week of Halloween. The “sacrifice” theory was finally put to rest when October 1982 passed without another child abduction in Salt Lake City.

Arthur Bishop

Authorities were baffled. Desperate for new leads, for anything at all, they rallied at the Metropolitan Hall of Justice in Salt Lake City. Representatives of the city police department gathered with detectives from the Salt Lake and Davis County sheriff’s offices, joined by agents of the FBI. They reviewed their open cases, stymied by the seeming lack of pattern. Each of the missing boys had been kidnapped at different times, on different days of the week, thereby frustrating any speculation on the kidnapper’s employment. Most killers prey on members of their own race, but Alonzo Daniels was African American, the later victims both fair-haired Caucasians. Kim Peterson was nearly three times the age of victims Daniels and Davis, casting doubt on the image of a pedophile stalking pre-school children.

In short, the meeting led investigators nowhere. The case was cold by June 23, 1983. Nearly two years had passed since the last disappearance in Salt Lake City, but the killer was about to return with a vengeance.

Troy Ward celebrated his sixth birthday that Wednesday afternoon. Permitted to play by himself at a park near his home, Troy was supposed to meet a family friend at 4:00 p.m., on a predetermined street corner. The friend would drive him home, where presents and a birthday cake were waiting. Come 4 o’clock, however, there was no sign of Troy on the sidewalk. His would-be chauffeur drove on to the Ward residence, expecting to find Troy there, but he had not returned from the park.

Police were called at once, patrol officers searching a grid of streets around the park. One witness, as related in the press, recalled a boy of Troy’s description leaving the scene with a man, on foot, a few minutes prior to 4:00 p.m. The man and boy had seemed at ease with one another, the witnesses assuming them to be father and son.

In fact, the man was Arthur Gary Bishop, and his fourth victim was gone without a trace. At home, Bishop repeated his grim ritual of fondling and molestation. He later told Detective Bell (quoted in the Deseret News) that he considered freeing Troy alive, but a last-minute threat to report the assault changed his mind. The hammer and bathtub were waiting. Afterward, instead of driving to his private graveyard outside Cedar Fort, Bishop drove east and buried Troy near Big Cottonwood Creek, in the Twin Peaks Wilderness Area.

It was all becoming so easy. He would not wait two years to claim his next victim. In fact, he would not even wait a month.

End Game

Graeme Cunningham, 13 years old, was looking forward to a weekend camping trip on Thursday, July 14, 1983. His gear was packed well in advance, and the adventure was his sole topic of conversation as departure time approached. If he was troubled by Troy Ward’s disappearance, three weeks earlier to the day, Cunningham hid it well. He would be camping with a junior high school classmate and an adult chaperone, one Roger Downs. What did he have to fear?

Graeme never made that camp out, however. Instead, he vanished from his neighborhood without a trace that Thursday afternoon, his parents alarmed when he failed to report home for dinner.

The disappearance made statewide news, and Roger Downs came calling to offer Cunningham’s mother any help that lay within his power. Later, in custody, “Downs” would tell detectives (quoted in the Deseret News), that his impulse was sincere. “I wanted to help her,” he said. “I just didn’t know how to tell her that I killed her son.”

However, a week later, he would indeed be confessing to that very sin. And so much more.

Roger Downs

Authorities went through the usual motions with Graeme Cunningham’s disappearance. The search was fruitless; their inquiries produced only blank stares or solemn denials, along with expressions of sympathy for the grieving family. This time, however, something clicked within the task force that had been pursuing Salt Lake City’s child killer since 1979. At last, detectives recognized the name of “Roger Downs.”

They didn’t know his real name yet, but suddenly they realized that “Downs” had been interrogated after each of the five unsolved vanishing acts. Incredibly, he had lived in close proximity to four of the victims and was known to the parents of the fifth.

Could it be that simple, after all their grueling efforts? Four years earlier, Chicago’s John Wayne Gacy had been trapped by a similar mistake, seen chatting with the last of his 33 victims shortly before the youth vanished. In fact, detectives realized, serial murder cases were usually broken exactly that way, by killers who let down their guard and made clumsy mistakes.

Sgt. Bruce White and Detective Steven Smith went back to question “Downs” again. They had no evidence against him yet, but there was something in his manner that suggested evasion. Was he one of those innocent persons who sometimes lie to the police instinctively, for no apparent reason, or was he concealing the worst of all possible secrets?

After brief preliminaries, “Downs” accepted an invitation to police headquarters. He was anxious to help find Graeme Cunningham, after all. Veteran homicide detective Don Bell was waiting for “Downs” on arrival. Slowly, surely, he began to pick apart the liar’s story. Soon, Bell had Arthur Bishop’s real name. By sundown, Bishop had confessed to five murders spanning four years.

Bell and Arthur Bishop spent most of the night together, nailing down details.

Retrieval of the dead would have to wait for dawn.

I’d Do It Again

The morning after his confession, Bishop led police to the remains of his victims, three sets of skeletal remains near Cedar Fort, and two more recent corpses near Big Cottonwood Creek. He was ambiguous about the motive for his murders, first claiming that he killed only those molestation victims who threatened to report him, later admitting the thrill he derived from murder itself. In either case, the crimes were compulsive. “I’m glad they caught me,” Bishop said, “because I’d do it again.”

A search of Bishop’s latest residence provided evidence to substantiate his confession. Police retrieved a .38-caliber revolver, a bloodstained mallet and hammer, plus dozens of photos depicting nude boys. Many of the photos were framed to exclude faces, making identification impossible, but they provided mute testimony to Bishop’s long career of child molestation.

Arthur Bishop was charged with five counts of capital murder, five counts of kidnapping, two counts of forcible sexual assault, and one count of sexually abusing a minor. The latter charges applied only to his most recent victims, in cases where forensic evidence of sexual assault was still available, and murder was the count that really mattered. If the state could prove its case, that charge would send him to his death.

Deputy County Attorney Robert Stott described Bishop as a ruthless killer and sexual deviant possessed of “a scheming, calculating, cunning mind.” Bishop, meanwhile, in his statements to police, made the crimes sound terribly simple. As Detective Bell later recalled, quoted in the Deseret News, Bishop told him, “You can offer [children] anything and they’ll go with you.”

That lesson was not lost on Bishop’s younger brother, apparently. Arthur was still awaiting trial in Salt Lake City when he learned that sibling Douglas had been jailed for sexually abusing young boys around Provo, in Utah County, south of Salt Lake City.

article continued below

WickedWe Recommends:

The Bradford Bishop Murders

At just 39 years old, United States Foreign Service Officer, William Bradford Bishop, had it all. A loving wife, three young boys and an adoring mother who resided with the family to help out with the children. But it was ‘the’ promotion that he really wanted. One he thought he deserved and was sure he would get. But then he didn’t.

When he was denied the promotion, he made some fast life changes. Starting with murdering, and burning, his entire family and vanishing from the face of the earth.

Nearly 50 years later he is still at large. He is now on the FBI’s ten most wanted list, He left a largely ignored trail through Africa, Italy, Sweden, and Croatia. With his prior background in the world of espionage, false documents, and visas, he baffled the World’s police.

Author David Casavis pieces together the evidence of a Foreign Service Officer mesmerized by success, and who sacrificed his family on the altar of his career. (Amazon)

Judgement Day for Arthur Bishop

Bishop’s defense team had no realistic hope of winning acquittal for their client. His confession had guaranteed a life behind bars, but the lawyers still tried to mitigate Bishop’s offenses, angling for a conviction on manslaughter charges rather than first-degree murder, with arguments that Bishop’s emotional and psychological “deficits” drove him to kill. And one of the culprits, they decided, was pornography.

And perhaps that was true. It did not however make any difference to the jury of five men and seven women at Bishop’s six-week trial in 1984. They convicted him on five counts of capital murder, five counts of aggravated kidnapping, and one count of sexually abusing a minor.

Only portions of Bishop’s taped confession had been played in court during the guilt phase of his trial, but jurors heard it all during the subsequent penalty phase. They listened, stone-faced or weeping, while Bishop giggled, sometimes lapsing into a falsetto voice to mimic a dying boy’s plea for mercy. It was no surprise to anyone in court when the panel recommended execution.

Judge Jay Banks made it official, condemning Bishop from the bench. State law gave Bishop the choice between execution by firing squad or lethal injection. Without a second thought, he chose the needle.

Misled By Satan

Soon after Bishop’s sentencing, while he sat on death row in Utah’s state prison at Point of the Mountain, Arthur spent his time rediscovering the religion of his youth. “With great sadness and remorse,” he said “I realize that I allowed myself to be misled by Satan.”

Repentance means a change of heart, though, and Bishop had not entirely abandoned his hopes for survival in this world. Attorneys pursued their petition for a new trial, but Utah’s Supreme Court rejected that bid on February 3, 1988. Only then did Bishop give up hope and resign himself to death.

On February 29 he filed a motion to dismiss his lawyers and replace them with counsel willing to abandon any further appeals. The trial court held a second competency hearing on Bishop and determined that he knew what he was doing. On May 2, 1988 the Utah Supreme Court lifted Bishop’s indefinite stay of execution and ordered the trial court to set an execution date.

Arthur Bishop appeared before Judge Frank Noel three days later, handcuffed and shackled, to read a brief handwritten statement. “In reflecting back on my life,” he said (quoted by AP reporter Robert Mims), “I remember a lot of good things, but these are overshadowed by the things I have done. I wish I could make restitution somehow, but I don’t see how I can. I wish I could go back and change what happened, or that by giving my life these five innocent lives could be restored. Again, I say that I am truly sorry for all the anguish.” Judge Noel, unmoved, signed the official death warrant and scheduled Bishop’s execution for June 10, 1988.

Back at Point of the Mountain, prison psychologist Al Carlisle told reporters that Bishop seemed to be a new man. He had read the Book of Mormon 10 times from cover-to-cover during his four years in prison, while using TV headphones to shield himself from the profanity of fellow inmates. Still, Carlisle told Robert Mims, Bishop feared that “his old impulses would come back” if he were someday freed. “I’ve seen remorse in him from the beginning,” Carlisle went on. “He believes he will be going into the spirit world, that it will be more peaceful than here. He doesn’t believe he’s been forgiven. He believes he can continue to work on the other side on these problems.”

Meanwhile, Carlisle said, Arthur Bishop had told his keepers that he was “ready and anxious to die.”

Last Goodbyes

Arthur Bishop met with his parents for the last time on June 8, 1988, then spent his last hours in fasting, declining a final meal, and prayer. “It’s unbelievable how calm and cool he is,” Mormon bishop Heber Geurts told newsman Robert Mims. “Even the guards can’t understand it. I’ve dealt with thousands of inmates in 33 years, and he’s the most sorrowful and repentant and remorseful man I’ve ever seen.”

Arthur Gary Bishop kept his date with the needle on June 10, 1988. He was 35 years old.

source: murderpedia | crime library | wikipedia | findagrave |

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links