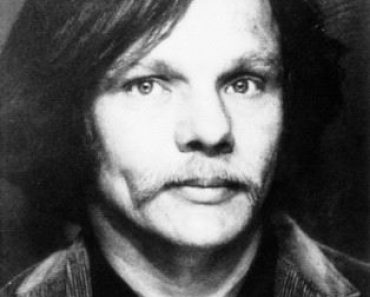

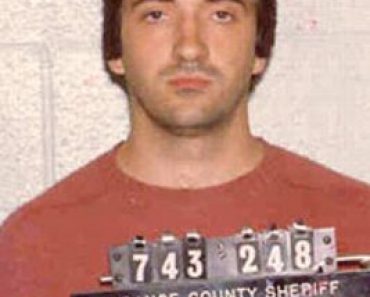

Nikko Jenkins – A Delinquent From The Start

Nikko Jenkins – A Delinquent From The Start

In 1993, a 7-year-old boy, Nikko Jenkins, showed up at Omaha’s Highland Elementary School with a loaded .25-caliber handgun.

He was briefly taken from his mother — which was the beginning of two decades in and out of group homes, the Douglas County Youth Detention Center and, eventually, state prison.

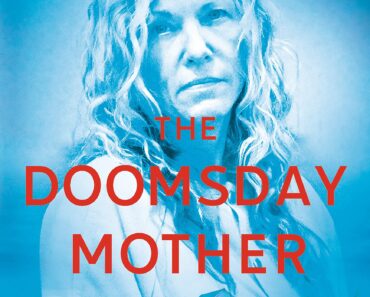

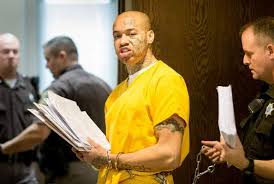

Nikko Jenkins has spent nearly his entire life in prison. When he finally won his freedom, on July 30th, he had acquired a face full of tattoos and a handful of female admirers each calling herself his wife.

Douglas County authorities now accuse him of a killing spree in August that left Jorge Cajiga-Ruiz, Juan Uribe-Pena, Curtis Bradford and Andrea Kruger dead.

“Nikko Jenkins maneuvered through his freedom by using fear, intimidation and violence to get what he wanted,” Omaha Police Chief Todd Schmaderer said.

Jenkins’ arrest left people wondering: Who is this man with the facial tattoos who’s accused of terrorizing the Omaha area for two weeks?

Nikko Jenkins

According to interviews and court documents, Nikko Jenkins was a menace who blamed his violent crimes on mental illness. Other times he was a charmer who wooed women and attempted to sway prosecutors, judges and even psychiatrists.

To this day, Douglas County sheriff’s deputies remember little Nikko as being barely tall enough to see over a counter in juvenile court.

After the gun incident at Highland Elementary, it was just four years until ‘little’ Nikko Jenkins was accused of a crime. At age 11, he admitted to stealing on three occasions. That was the last time he was free for any significant period.

It was also around then that he stopped regularly attending school, though he later said he completed his GED in prison.

At first the preteen Nikko Jenkins was sent to a group home in Papillion, and his actions soon escalated to violence. In 1998 he was kicked out of the home for repeatedly assaulting other children.

Nikko Jenkins

“The latest incident occurred on February 26, 1998, when he used a clothes hanger to hit another child, leaving whip marks on this minor.

Nikko Jenkins was sent to the Youth Detention Center, then soon released to the care of his mother, Lori Jenkins. But, by the end of the year, the 12-year-old boy was back in the detention center for assaulting someone with a knife.

Eventually he had caused so much trouble and run away so many times that his probation was revoked. In August 2001 he was sent to the Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center-Kearney. But one year later he was back in Omaha, and soon he began threatening those around him.

His father, David Magee, wrote in court documents that “Nikko Jenkins has threatened my life and pulled a sawed-off shotgun on me at my own home.”

Nikko Jenkins

Nikko Jenkins

Soon after, Nikko Jenkins stole two cars at gunpoint. In one incident he ordered a 21-year-old man out of his black Honda Civic and took off in it.

In the second incident he asked a 20-year-old woman for a ride. When she declined, he got into the back of her 1983 maroon Cadillac DeVille, brandished a shotgun and told her to drive to 22nd Street and Grand Avenue. There, he ordered her out.

For the robberies, Jenkins was sent to prison in 2003, and he wasn’t released for a decade.

The violence didn’t end in prison. He was charged twice: once for assaulting a guard while on furlough at his grandmother’s funeral and once for his part in a prison riot.

He also was disciplined several times for his tattoo activities, attacking other inmates, gang activity and fashioning a weapon out of a toilet brush.

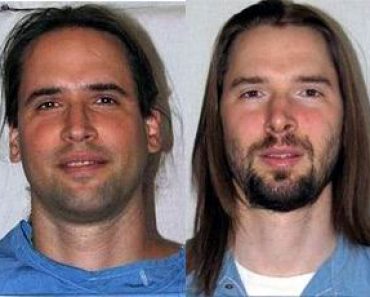

Once he got out, Nikko Jenkins reconnected with his family, his female friends and a prison buddy: Curtis Bradford.

Bradford’s family warned him about Jenkins, a relative said. But Bradford wouldn’t listen, and he even posted a picture of himself with Nikko Jenkins on Facebook the day before he died.

Nikko Jenkins

“He just got caught up in the wrong crowd,” the relative said.

Friends and relatives say Bradford and Nikko Jenkins might have been trying to rob someone the night Bradford was shot in the back of the head.

Nikko Jenkins attributed his problems to mental illness.

He told a psychiatrist of a family history of mental illness and said he first went to a psychiatrist at the former Richard Young Center when he was 8 or 9. He said a Tecumseh State Prison doctor diagnosed him as schizophrenic, bipolar and obsessive-compulsive.

In several hearings before Douglas County District Judge Gary Randall, Nikko Jenkins kept trying to enter an insanity plea. At the same time, he consistently told corrections officers and a judge that he wasn’t going to take medications for his mental illness.

“You’ve chosen not to take those?” Randall asked Jenkins at a sentencing hearing in July 2011.

Nikko Jenkins

Nikko Jenkins

“Because of the hostile environment that I’m currently living in,” Nikko Jenkins said. “The medication is to basically kill my adrenaline, because when I have mental breakdowns, I become enraged and I lash out on others. So the medicine that they give me, it slows me down and it basically puts me in almost a paralyzing, you know, state of mind.”

Nikko Jenkins told the judge that his attack on a Tecumseh corrections officer was “a mental breakdown as a result of my mental disorders.”

But a psychiatrist evaluating Jenkins’ ability to stand trial in 2010 wrote that he believed the inmate was making up at least some of his symptoms.

Randall had ordered an evaluation by a Lincoln Regional Center psychiatrist. On July 20, 2010, Dr. Scott Moore met with Nikko Jenkins at the Douglas County Correctional Center.

He told the doctor that his problems stemmed from abuse he said he suffered at the hands of family members when he was young. He went on to say that he heard voices from Egyptian gods. That wasn’t all, Moore wrote in his report.

He told the doctor that his problems stemmed from abuse he said he suffered at the hands of family members when he was young. He went on to say that he heard voices from Egyptian gods. That wasn’t all, Moore wrote in his report.

“After a little bit, (Jenkins) went on to tell me that he was told that he should eat human brains because that’s where the pituitary gland was and it would strengthen him to do so.”

Moore’s conclusion: Nikko Jenkins was faking it.

The judge gave him death! stating – “The defendant’s commission of these four murders over a 10-day period is one of the worst killing sprees in the history of this state,” Bataillon said, reading from the order signed by himself, Judge Mark Johnson of Madison and Terri Harder of the Kearney area. “This panel finds that the aggravating circumstances, as determined to exist, justify the imposition of a sentence of death for each murder.” (By Todd Cooper / World-Herald)

edit murderpedia / Roseann Moring and Todd Cooper