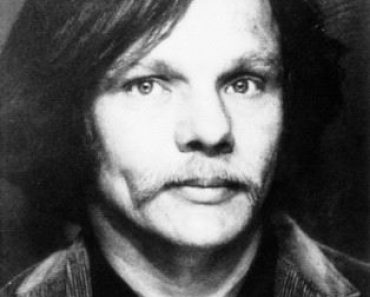

Kimberly Hricko

Was She Really An Arsonist and Murderer?

Kimberly Hricko admits that her marriage was not perfect but says she would never kill her husband. Not even for $200,000 in insurance money.

Kimberly Hricko admits that her marriage was not perfect but says she would never kill her husband. Not even for $200,000 in insurance money.

A Maryland jury didn’t quite believe her.

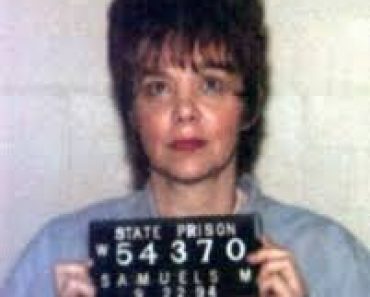

After finding her guilty of both murder and arson, jurors sentenced Kimberly Hricko to life in prison, plus thirty years concurrent. Now, Kim and her family, are hoping to prove the jury wrong and help Kimberly see justice.

What Happened

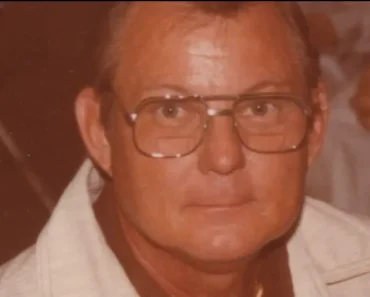

The jury found that on the night of February 15, 1998, Kimberly Hricko poisoned her husband Stephen, then set his body on fire. Kim and Stephen Hricko were at a resort, hoping to recapture the romance they once shared. It was Valentine’s weekend and the resort was putting on a murder mystery play with audience participation. Kim told police that, back in their room after the play, she and her husband had an argument, and she left. She said she went to visit a friend, but became lost. She drove around for a while, then headed back to the resort.

Upon returning to their room, Kim claims she entered through a back door, then noticed the room was filled with thick smoke. Witnesses said Kim ran into the hotel lobby, cell phone in hand, frantically calling the fire department. When firefighters arrived, the fire was already out, but Stephen was dead. He was found lying on the floor between the two beds, flat on his back, with his pants around his knees. A Playboy magazine lay nearby.

Upon returning to their room, Kim claims she entered through a back door, then noticed the room was filled with thick smoke. Witnesses said Kim ran into the hotel lobby, cell phone in hand, frantically calling the fire department. When firefighters arrived, the fire was already out, but Stephen was dead. He was found lying on the floor between the two beds, flat on his back, with his pants around his knees. A Playboy magazine lay nearby.

Stephen Hricko Was Dead Before The Fire Started

Kimberly Hricko told police that her husband often looked at pornography. In her statement to police, she said that Stephen was “sloppy drunk” when she left during the argument. Even though witnesses saw him drinking during the murder mystery play, the autopsy showed no sign of alcohol in his body. However, the autopsy did show a normal level of carbon monoxide in his lungs, indicating that he was dead before the fire started.

The prosecution alleged that Kim injected her husband with a lethal dose of Succinylcholine, a drug that paralyzes the muscles during surgery, before setting fire to his body. Prosecutors alleged that Kim, who worked at a local hospital, had access to the drug.

The prosecution alleged that Kim injected her husband with a lethal dose of Succinylcholine, a drug that paralyzes the muscles during surgery, before setting fire to his body. Prosecutors alleged that Kim, who worked at a local hospital, had access to the drug.

But the autopsy did not detect any Succinylcholine in Stephen’s body, and no needle tracks were observed. A medical examiner testified that at least 10 cc’s of the drug would be required to stop Stephen’s breathing. Also, the State’s own witness testified that it would take at least three minutes to inject that much Succinylcholine. An FBI lab conducted eight different tests on Stephen’s urine, and Mark Lebeau of the FBI testified that no trace of Succinylcholine was detected in the urine.

The Prosecutions Claimed Kim Hricko Set The Fire

The prosecution claimed that Kimberly Hricko set the room on fire after giving her husband the lethal injection. Maryland State Police Officer John Tobin investigated the scene for accelerants. He testified that he found no trace of ignitable liquid. Even with no evidence of arson and no proof that any drug had been injected into Stephen’s body, the State stuck to its theory.

So what caused the fire? Why wasn’t Stephen able to escape? Kim’s supporters think her husband mixed the wrong drugs with alcohol and passed out. They also think that a faulty wood stove or Stephen’s carelessness might have caused the fire. Recent prescriptions indicated that Stephen was taking antidepressants and muscle relaxers, which the autopsy detected. The muscle relaxant Stephen was taking, Cyclobenzaprine, warns against taking the drug with antidepressants or alcohol. He apparently did both.

At the time of the fire, the room’s wood stove was using commercial fire logs. Most fire log labels clearly warn against using the product in wood stoves. Also, it was alleged that the furnace in the Hrickos’ room was replaced after the fire because it was malfunctioning.

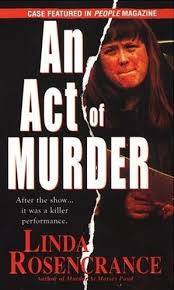

The Murder Mystery Weekend Killing

The local press sensationalized the trial, dubbing it “The Murder Mystery Weekend Killing.” Cathy Rosenberger, a local realtor who recently had sold a house to the Hrickos, sat through the entire trial. She was amazed that the attorney working for Kim Hricko did not ask for a change of venue.

The trial was long and tedious, and too stressful on the jury, some say.

Court began at 8:30 a.m. sharp, and continued until 7:30 p.m.. Rosenberger says the long days took a toll on the jury and attorneys. “The judge made it very clear from the beginning that he wanted the trial and verdict wrapped up within a week’s time,” says Rosenberger.

Without any clear evidence that Kimberly had drugged and killed her husband or set the fire, the prosecution went full speed ahead. They called Ken Burgess, Kim’s co-worker. Burgess testified that Kim had offered him money to kill her husband. When asked how much she offered, he could not remember whether it was $5,000 or $50,000. He also admitted to being caught and punished for welfare fraud in Virginia. According to police records, Burgess placed three controlled calls to Kim, in which he tried unsuccessfully to get Kim to discuss what happened to Stephen.

Damage Without Evidence

Several other key witnesses took the stand — girlfriends who testified they had actually heard Kim talking about killing Stephen, and a man with whom Kim Hricko once had an affair. Although none actually linked her in any way to the crime, they were very damaging to Kim’s character, and may have played a large part in the jury’s decision.

The Kim Hricko case is very much like the Darlie Routier case in Texas. Both young women are in prison for allegedly killing family members. In both cases, the prosecution had no physical evidence linking the women to the crime. There were no eyewitnesses to the crimes and no confessions. Also in both cases, the lead detectives mysteriously lost their notes before testifying. Still, through pure conjecture and character assassination, prosecuting attorneys were able to convince juries that both defendants were guilty. This is a sad commentary about either the American justice system or the intelligence of American juries. Maybe both.

Kim Hricko is not granting media interviews, on the advice of her appellate attorney. In written correspondence, she says that she “can’t help but cry” as she composes the letter. “I am so frustrated,” she writes. “Here I sit in my cell with a sentence of life plus thirty concurrent and I am innocent.”

credit – murderpedia