Gerard Schaefer | Serial Killer

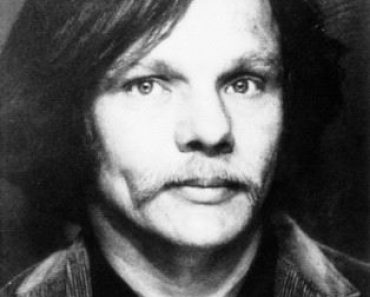

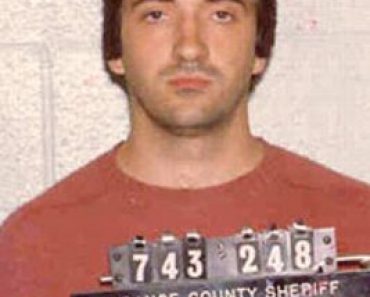

Gerard Schaefer

Born: 03-26-1946

The Butcher of Blind Creek

American Serial Killer

Crime Spree: 1966–1973

Death: Murdered in prison on 12-03-1995

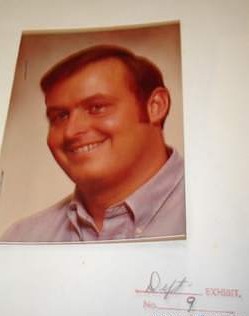

Gerard Schaefer was born in Wisconsin on March 25, 1946, the oldest of three children in a family he later describes as “turbulent and conflictual.”

Years later, interviewed by court-appointed psychiatrists, he would refer to himself as “an illegitimate child,” the product of a hasty shotgun wedding. He describes his father as a verbally abusive alcoholic, flagrantly adulterous and often absent from home on business trips or otherwise.

By 1960, Gerard Schaefer’s family had settled in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He graduated high school there in 1964, and he was working on the first of several college degrees when his parents divorced three years later.

Troubles From The Start

By that time, if we accept Schaefer’s statements to psychiatrists, he was well on the way to troubles of his own. “From an early age,” Dr. Eaton recorded in 1973, “Gerard Schaefer has had numerous sexual hang-ups.”

Experiments with bondage and sadomasochism began around age 12. “I’d tie myself up to a tree,” he told Dr. Mordecai Haber, “and I’d get excited sexually and do something to hurt myself.” Around the same time he began to “masturbate and fantasize about hurting other people, women in particular.” As if this weren’t enough, Schaefer recalled, “I discovered womens underwearpanties. Sometimes I wore them. I wanted to hurt myself. “

The violent self-loathing went back to his earliest childhood games. In those games, he told Dr. Haber, “I always got killed. I wanted to die. My father favored my sister, so I wanted to be a girl. I wanted to die. I was such a disappointment to my family as a kid, to my father. He loved my sister. I couldn’t please my father so, in playing games, I wanted to be killed.”

Gerard Schaefer Seeks Help

Gerard Schaefer claimed to have visited a psychiatrist in 1966, seeking relief from his sexual deviance and homicidal fantasies, but therapy didn’t help. If his later statements are credible, he kept on hearing voices “telling him to kill.” That same year, he toured the South with Moral Rearmament, the cheery “Up With People” folks who sang that freedom isn’t free. Gerard Schaefer thought about the priesthood as a calling, but he was turned away from St. John’s Seminary, where, he recalled, “they said I didn’t have enough faith.” The rejection angered Schaefer so much that he quit the Catholic Church.

His next goal was a teaching job, through which he hoped to instill “American values” like “honesty, purity, unselfishness and love.” But Schaefer was twice dropped from the student~teaching programs for “trying to impose his own moral and political values on his students.” The second time, supervisor Richard Goodhart recalls, “I told him when he left that he’d better never let me hear of his trying to get a job with any authority over other people, or I’d do anything I could to prevent ¡t. “

In 1968, Gerard Schaefer married Martha Fogg, but ¡t didn’t work out. Martha filed for divorce in May 1970, claiming “extreme cruelty.”

Gerard Schaefer Has A New Goal

Schaefer took a few weeks to recuperate in Europe and North Africa that summer, coming home with a new goal in life. If he couldn’t be a priest or a teacher, he would be a policeman. He applied to several departments and was rejected by the Broward County sheriff’s office after failing a psychological test, but the small Wilton Manors Police Department hired him anyway.

In March 1972, Gerard Schaefer earned a commendation for his role in a drug bust. One month later, on April 20, he was fired. Explanations vary. Chief Bernard Scott said that Schaefer didn’t have “an ounce of common sense,” while ex-FBI Agent Robert Ressler reports that Gerard was disciplined for running female traffic violators through the departments computer, obtaining personal information and later calling them for dates.

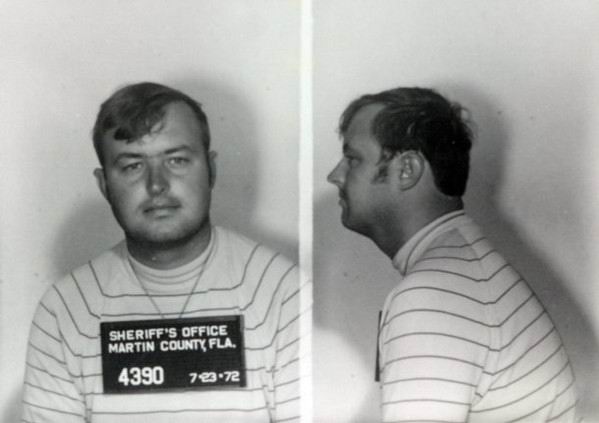

Whatever the cause of his firing, Gerard Schaefer needed a job. Near the end of June, he signed on with the Martin County Sheriff’s Department, pulling up stakes and moving to Stuart, Florida. He had been on the job less than a month when he made a “dumb mistake” that would cost him his career and his freedom.

Gerard Schaefer Makes A Grave Mistake

On July 21, 1972, Gerard Schaefer picked up two hitchhikers, 17-year-old Pamela Wells and 18-year-old Nancy Trotter, on the highway near a local beach. He told them (falsely) that hitchhiking was illegal in Martin County, then drove them back to a halfway house where they were staying.

Schaefer offered to meet them next morning, off duty, and drive them to the beach himself. The girls agreed, but instead of taking them to the beach on July 22, Schaefer drove them to swampy Hutchinson Island off State Road AlA.

There, he started making sexual remarks, then drew a gun. He told the girls he planned to sell them as “white slaves” to a foreign prostitution syndicate. Forcing them out of the car, he bound both girls and left them balanced on tree roots, with nooses around their necks, at risk of hanging if they slipped and fell. Gerard Schaefer left them then, promising to return shortly, but the girls escaped in his absence and reached the highway. They flagged down a passing police car. They had no problem identifying their assailant, since Schaefer had told them his name.

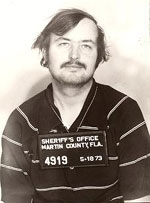

Gerard Schaefer Was Arrested

By that time, Gerard Schaefer had discovered their escape and telephoned Sheriff Richard Crowder. “I’ve done something foolish,” Schaefer told his boss. “You’re going to be mad at me.” He had “overdone” his job, Schaefer said, trying to “scare” the girls out of hitchhiking in the future for their own good. Fired on the spot, charged with false imprisonment and two counts of aggravated assault, Schaefer was released on $15,000 bond.

At trial in November 1972, he pled guilty on one assault charge and the other counts were dropped. Judge Smith called Schaefer a “thoughtless fool” and sentenced him to a year in county jail to be followed by three years’ probation. The ex-deputy began serving his sentence on January 15, 1973.

The most shocking revelations were yet to come, however. Two other girls were missing from the neighborhood, and they would not be as lucky as Trotter and Wells.

On September 27, 1972, while Schaefer was free on bond pending trial, 17-year-old Susan Place and 16 year-old Georgia Jessup had vanished from Fort Lauderdale. Susan’s parents said the girls were last seen at her house, leaving with an older man named “Gerry Shepherd” on their way to “play guitar” at a nearby beach. They never came back, but Lucille Place had noted Schaefers license number, along with a description of his blue-green Datsun. lt was March 25, 1973, before sluggish investigators traced the plate number back to Gerard Schaefer by which time he was already in jail for assaulting the teenage girls.

Gerard Schaefer Denies Any Contact

Gerard Schaefer denied any contact with Place and Jessup, but the case began unraveling on April 1, 1973, when skeletal remains were found on Hutchinson Island by three men collecting aluminum cans.

Four days later, the victims were identified from dental records. Susan Place had been shot in the jaw. Detectives remarking that evidence from the crime scene indicated the two girls were “tied to a tree and butchered.”

On April 7, police searched the home of Schaefer’s mother, where Gerard had personal items stored in a spare bedroom. Evidence recovered in the search included a stash of women’s jewelry, 100-plus pages of writing and sketches depicting mutilation-murders of young women, newspaper clippings about two women missing since 1969, and pieces of I.D. belonging to vanished hitchhikers Collette Goodenough and Barbara Wilcox, both 19. The two girls had last been seen alive on January 8, a week before Gerard Schaefer was sent to jail in Martin County.

The News Clippings Found

As for the news clips, one referred to the February 1969 disappearance of waitress Carmen Hallock, seemingly abducted from her home. Items of her jewelry were found in Schafer’s hoard, along with a gold-filled tooth identified by Hallocks dentist, but once again no charges were filed.

The second missing woman, Leigh Bonadies, had been a neighbor of Schaefer’s when she disappeared in September 1969. He had complained of her “taunting” him by undressing with her curtains open, and a piece of her jewelry was found among his belongings, but no charges were filed when her skeletal remains were finally recovered in 1978.

More jewelry linked Gerard Schaefer to the disappearance of 14-year-old Mary Briscolina, who vanished from Broward County with 13-year-old Elsie Farmer in October 1972. Their skeletons were found in early 1973, but once again no cause of death could be determined and no charges were filed.

The list of suspected victims would grow over time, but Gerard Schaefer faced charges in only two murders. He was indicted on May 18, 1973, for the slayings of Jessup and Place. Held without bond pending trial, he was convicted on two counts of first-degree murder in October 1973, drawing concurrent terms of life imprisonment. Numerous appeals, some 20 in all, were uniformly rejected by various state and federal courts.

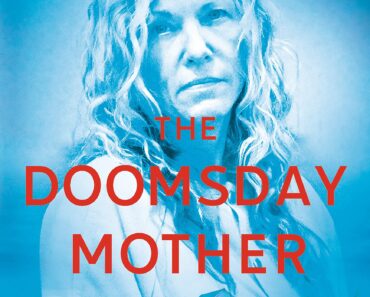

Gerard Schaefer Starts To Write

Schaefer was nearly forgotten by 1990, when former high school girlfriend Sondra London published a collection of his stories under the title Killer Fiction. More volumes followed, Gerard Schaefer insisting that his stories were art, police and prosecutors describing them as thinly veiled descriptions of actual crimes.

In private letters to attorneys and acquaintances, Schaefer admitted as much, himself. Witness his reference to a story titled “Murder Demons,” in a letter dated April 9, 1991: “What crimes am I supposed to confess? Farmer? Briscolina? What do you think “Murder Demons” is? You want confessions but don’t recognize them when I anoint you with them and we’ve just gotten started.”

Other correspondence swiftly raised the body count. “As you know,” he wrote on January 20, 1991, “I’ve always harped on District Attorney Robert Stone’s list of 34. In 1973 I sat down and drew up a list of my own. As I recall, my list was just over 80.” The next day, given more time to reflect, Gerard Schaefer went on: “I’m not claiming a huge number. I would say it runs between 80 and 110. But over eight years and three continents. One whore drowned in her own vomit while watching me disembowel her girlfriend. I’m not sure that counts as a valid kill. Did the pregnant ones count as two kills? lt can get confusing.”

The Letters of Gerard Schaefer Come Back To Haunt Him

Years later, Gerard Schaefer’s letters came back to haunt him when he was described, in several true-crime books, as a prolific serial killer. His response was a series of lawsuits filed against various authors for libel. They were uniformly dismissed by the courts. In one such case, Judge William Steckler officially branded Schaefer a serial killer, finding him “undeniably linked” to numerous murders beyond the two for which he stood convicted. “He boasts of the private and public associations he has based on the reports that he is a serial killer of woríd-class proportions,” Steckler wrote, “And it is only arrogant perversity which propels him toward this and similarly meritless lawsuits in which he claims otherwise.”

Schaefer’s luck tan out on December 3, 1995, when another inmate barged into his cell, slashed Schaefer’s throat, and stabbed him in both eyes. Prison officials named the killer as inmate Vincent Rivera, serving life plus 20 years for two murders in Tampa. But no specific motive has been offered. lt appears that Schaefers reputation as a “rat” and troublemaker in the joint caught up with him at last.

source: murderpedia – as told by Michael Newton

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links