George Emil Banks | Family Annihilator

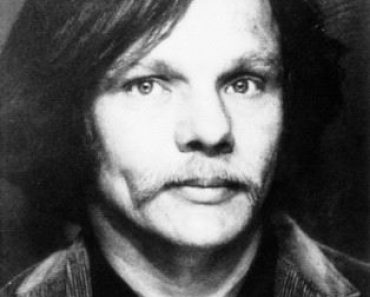

George Emil Banks

Bath: 06-22-1942

The Wilkes-Barre Shootings

Mass Murder | Familicide

Crime Spree: September 25, 1982

Incarcerated on death row in Pennsylvania

George Emil Banks was an American mass murderer and a family annihilator. He was a former Camp Hill prison guard who shot 13 people to death on September 25, 1982 in Wilkes-Barre City and Jenkins Township, Pennsylvania, including five of his own children in cold blood.

The Story of George Emil Banks

A Day of Madness

In the early morning hours of September 25, 1982, George Banks awoke from a self-induced haze. He forced his eyes to focus and looked at his surroundings. Lying next to him was an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, which he had purchased the previous year. His four-year-old son, Bowendy, was sleeping next to him while his girlfriends, 29-year-old Regina Clemens, 23-year-old Susan Yuhas, and 29-year-old Dorothy Lyons, sat in chairs nearby. Susan, cradling the couple’s one-year-old daughter Mauritania in her arms, awoke when George began to stir.

George reached down and picked up the gun, locked and loaded it with a thirty-round clip. Most likely, his facial expression began to change as he stroked the military-style assault rifle, his eyes burning with anger and a scowl tainting his generally handsome features.

Lacking explanation or any apparent compassion, he raised the weapon and shot Regina Clemens. The bullet pierced her right cheek, sliced downward and traveled directly through her heart, killing her instantly. Her body pitched sideways in a lifeless sprawl.

George Emil Banks Goes On A Rampage

Susan and Dorothy, frozen with fear, watched in horror as George stood there momentarily emotionless, before turning his glare on them. He suddenly fired again, this time shooting Susan five times in the chest at point blank range as her cries for mercy fell on deaf ears. A single bullet entered Mauritania’s left ear and exited her right eye as her mother Susan had tried in vain to safeguard her from the hail of bullets.

Dorothy must have known that she was to be next for she shielded her face with her right arm as George fired two more rounds. The first bullet pierced her arm and chest; the second entered her neck as she fell forward to the floor.

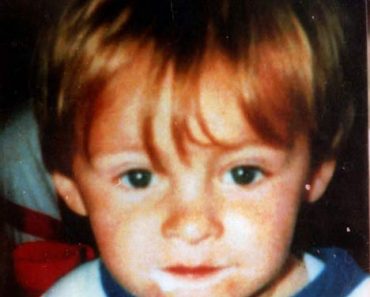

Bowendy’s young face turned away from his father when a single shot rang out; the bullet traveled through his left cheek and exited his right ear, virtually turning his face inside out. The AR-15 fell abruptly silent as George stood amidst the carnage he had inflicted upon his family. Spent cartridges littered the floor and the smell of gunpowder and death permeated the air. His taste for blood had yet to be quenched. He was a man on a deadly mission, and there was still much to do. He made his way up the stairs towards his children’s bedrooms.

Moving down the hall, George stopped at eleven-year-old Nancy Lyons’ room. She was sitting up on her bed holding her half-brother one-year-old Forarounde Banks in her arms. The young girl saw the anger in his eyes, and attempted to shield her brother as George stood up on the bed and took aim. There were three shots fired in rapid succession. Forarounde was shot in the back of the head, the bullet exiting his left eye. A bullet struck Nancy in the left forearm and one directly in the face that immediately shattered her skull. Both children lie dead as he walked out of the room. George made his way to his bedroom, his clothes splattered with blood, where he donned military style fatigues and a T-shirt that read, “Kill ‘em all and let God sort ‘em out.”

Across the street from Banks’ house, 22-year-old Jimmy Olsen and 24-year-old Ray Hall, Jr. heard the multiple gunshots and decided to get out of the area. As they approached their car, George walked out of his house. Banks immediately ran up to them, “You’re never going to live to tell anyone about this!” he exclaimed as the gun expelled a flurry of bullets at the two men. Hall and Olsen were both struck point blank in the chest and fell to the pavement. Banks stood over their bodies only momentarily before getting into his vehicle and driving off.

Not Finished Yet

George drove approximately four miles from the crime scene at School House Lane to Heather Highlands trailer court in Plains Township. A former girlfriend, Sharon Mazzillo, along with the couple’s son Kissamayu Banks, shared a mobile home there with Sharon’s mother, Alice Mazzillo, her brothers Keith and Angelo Mazzillo, and visiting nephew Scott Mazzillo.

George Banks walked up to the front door. 24-year-old Sharon cautiously greeted him at the door. When she saw the rifle in his hand, she tried to close the door but George was having none of that.

Quickly tiring of Sharon’s resistance, George raised the weapon and fired. The bullet ripped through her chest and severed the main blood vessel to the heart. Her limp body slumped to the ground. George stepped over it and entered the house. He saw five-year-old Kissamayu laying on the couch with a blanket pulled over his head. George walked up to the child, placed the barrel of the gun just inches from his forehead and fired a single shot.

Sharon’s mother, 47-year-old Alice, had heard the shots and was desperately trying to phone for help. Her two sons, 10-year-old Angelo and 13-year-old Keith were looking for a place to hide. Angelo crawled under Alice’s bed while Keith hid in the closet. George entered Alice’s room, walked over to her and strategically placed the barrel of the gun at an angle aiming directly up her nasal passage. He fired one shot. The combination of the combustion from the discharge and the exiting bullet caused Alice’s head to explode, scattering brain matter all over the room.

Keith watched in horror through the partly opened closet door as seven-year-old Scott Mazzillo ran into the room and screamed. When Scott saw the horrible scene in the bedroom, he ran down the hall. George grabbed him, kicked him to the ground and punched him repeatedly in the back. When he stopped struggling, George pulled the sobbing boy up by the shoulder, placed the barrel just behind the left ear and fired. George removed his hand and allowed the lifeless child to fall to the floor. Satisfied that he had left no survivors, George stood up, walked out the front door and yelled, “I killed them all!” before fleeing the scene.

article continued below

prime video | start your free trial today

Watch All Your Favorites and A Few You Don’t Want To Miss

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links

article continued below

The Carnage

Sometime around 2:30 a.m., Jenkins Township Patrolmen, John Darski and Detective Captain, Ray McGarry, while on routine patrol, received a call instructing them to investigate a possible shooting in Heather Highlands. As the two veteran officers turned into the park entrance, they had no way of knowing the horror and carnage that they were about to witness.

Upon reaching lot 188, they immediately noticed that a Caucasian female, covered with blood, was lying next to the steps of the home. She had no vital signs and it was apparent that she had died as a result of at least one gunshot wound. Cautiously entering the trailer, the officers discovered Kissamayu on the couch, Scott, laying face down and dead in the hallway and the decapitated body of Alice in the bedroom.

Realizing they were no longer in danger, Keith and Angelo came out from hiding. Officers on the scene, while sick to their stomach from the bloody massacre, were relieved that at least two children had survived. While obviously in a state of shock, the boys were able to tell the officers that George Banks was the man who had committed the appalling crimes. The officers immediately put out an all-points bulletin for Banks’ arrest.

At about the same time, Wilkes-Barre Police Lt. John Lowe, was en route to discovered the bodies of two Caucasian males lying next to the street on Schoolhouse Lane.

George Emil Banks

Uncertain as to whether the perpetrator, or perpetrators, was still in the general vicinity, Lowe quickly made his way up to a small white house across from the victims’ bodies and cautiously stepped inside. Hoping to spot the gunman in the home, he shined his light around the interior. A nightmarish scene greeted Lowe. The smell of fresh gunpowder still saturated the air and there were corpses scattered about the rooms.

Paramedics dispatched to the scene immediately treated James Olsen and Raymond Hall. Both men had sustained serious injuries and were in critical condition upon their arrival at Wilkes-Barre General Hospital. While the paramedics were treating the wounded, the local police department was just arriving at the scene. Wilkes-Barre Detective Tino Andreoli was one of the first investigators to arrive at 28 School House Lane. Detective Patrick Curley greeted him solemnly as he walked up to Banks’ front door:

Detective Andreoli was horrified as he entered the home; in all of his years on the force he had never encountered anything like the slaughter that now presented itself. The rooms were blood-splattered and riddled with bullets. The detectives wondered to themselves how a person could murder young, innocent children in such a heinous cold-blooded manner?

Police had cordoned off all routes out of the city and were desperately trying to find their murder suspect. George was well aware of the manhunt and decided to change vehicles to elude police. After deserting his vehicle, he stopped a motorist near the Cabaret Lounge in Wilkes-Barre. George put his gun to the man’s head and forced him out of his vehicle. He drove the man’s ’72 Chevy to the east-end section of the city and then abandoned it. Still feeling the effects of the alcohol and drugs that he had consumed earlier, George walked into a desolate area, lay down in the grass and passed out.

At Wilkes-Barre General Hospital at 3:30 a.m., Raymond Hall, Jr. was pronounced dead. A Life Flight helicopter rushed James Olsen to Geisinger Medical Center in Danville as his condition deteriorated.

Mary Banks Yelland

Police were still searching for Banks. Patrol cars spread out through the city shining lights in back yards and alleyways hoping to catch a glimpse of the dangerous fugitive. Around 5:30 a.m. George awoke, still wearing his military fatigues, his rifle at his side. Uncertain what to do, he ran to the home of his mother, Mary Banks Yelland, located at 98 Metcalfe Street. George was crying and smelled like liquor when his mother opened the door:

Banks: “Mom, if you don’t take me where I want to go, there will be a shootout here and you will be hurt.”

Yelland: “George, what’s wrong?”

Banks: “It’s all over, Mom. It’s all over. I did it. I killed everyone.”

Yelland: “Who did you kill, Georgie? Who did you kill?”

Banks: “I killed them all, Mom. I killed all the kids and girls. Regina, Sharon, them all.”

Yelland: “Georgie, no!”

Banks: “It’s all over, Mom. It’s all over.”

Following the conversation with his mother, George sat down at her kitchen table and began writing a crude will leaving her all of his possessions. Mary Banks Yelland was in a state of shock and decided to phone George’s home in the hopes that what he had confided in her was simply part of his drunken imagination. Chief County Detective Jim Zardecki answered the phone at School House Lane when it rang. George grabbed the phone from his mother and identified himself:

Banks: “This is George Banks, how are the kids?”

Zardecki: “They are alive, George”

Banks: “You’re lying, I know I killed them!”

Banks hung up the telephone. Zardecki had hoped that if George thought the children were still alive, he could keep him on the phone long enough for police to locate him. He was wrong. Banks placed three 30-round clips and numerous other rounds of ammunition into a bag and asked his mother to drive him to a friend’s recently vacated rental house at 24 Monroe Street. Yelland did as George requested, dropped him off in front of the house and drove away. When she got home, she was greeted by a phalanx of police and hesitantly told them where she had just taken her son.

Not Buying The Lie

By 7:20 a.m., the Wilkes-Barre Police Department, Luzerne County Sheriff’s Department, and Pennsylvania State Police had the house on Monroe Street surrounded with officers. Banks had barricaded the doors with furniture and kicked out a first floor bedroom window of the two-story home when he saw officers arriving at the scene. Approximately 110 law enforcement officers prepared themselves for a possible shoot-out with Banks.

Wilkes-Barre Detective Patrick Curley and Luzerne County Chief Detective James Zardecki took turns on a loud speaker attempting to get George to surrender and urging him not to do anything that would endanger himself or others. Banks screamed back about living in a racist community and not wanting his kids to grow up in a racist world. Whenever he noticed an officer’s position, he would call it out and threaten to shoot. Detectives Harold Crawley and Jerry Dessoye were hidden across the street from Banks’ location and on several occasions noticed that they would be able to get a clear shot at Banks whenever he came near the window to yell out. However, upon radioing in for permission, they learned that Chief John Swim would not authorize any such action, “If you fire a shot and miss, or just wound him, God knows what will happen.”

At approximately 8:15 a.m. Chief Detective Zardecki went to a nearby phone and called Banks, attempting to use the ploy that his children were still alive again. “George, you’ve got to care about your kids. They need your blood to survive. Come out, George, you’ve got to take care of your children.” Banks replied that he might consider coming out but that he doubted any of the children were still alive. Just before slamming the receiver down, Banks informed Zardecki that he wanted a transistor radio so he could listen to news reports regarding the events.

Shortly after 9:00 a.m., police brought George’s mother to the scene with hopes that she could talk him out. Mrs. Yelland spoke to her son over the police loudspeaker:

Yelland: “Come out for my sake Georgie. I love you. Please son, please. None of your children is dead. Believe me.”

Banks: “I want them to kill me!”

Yelland: “No, you’ve been taking that medicine.”

Banks: “I’m tired. I want them to kill me.”

In an effort to end the drama, District Attorney Robert Gillespie asked local radio station WILK for help. Convinced that if Banks heard a newscast that his children were still alive, he would give himself up. WILK News Director Pat Ward agreed to Gillespie’s plan to go on the air and report the erroneous facts that Banks’ children were not dead although “seriously injured.” A radio was brought to the scene at 9:58 a.m. Officers began playing it over a police loud speaker. Following the newscast, Banks informed officers that he did not believe the report and was not going to surrender.

Wilkes-Barre policeman Dale Minnick attempted to talk Banks out of the house shortly after the false radio broadcast. “You heard the broadcast over the radio,” Minnick conveyed to Banks over a bullhorn. “Throw out your gun and come out. We wouldn’t lie to you. You can go down to the hospital and see your kids. It’s been a long day for you and us. Throw your gun out the window. You heard it on the radio, what more do you want from us?” Minnick’s words had no affect on Banks, who kept quiet during the entire one-sided conversation.

Robert Brunson

Robert Brunson, a resident of Wilkes-Barre, friend and former co-worker of George Banks, heard reports on the news of the standoff on Monroe Street and felt compelled to help. The unemployed and divorced 36-year-old man quickly drove to the scene, and asked the permission of Wilkes-Barre Chief of Police John Swim to talk with Banks, “I feel I can talk to him and would like a chance to try,” Brunson told Swim. With few options left on the table, Swim agreed. Brunson, escorted to a point only a few yards from the home, called out to Banks:

Brunson: “George, can I talk to you before you die? If you came here to die, so be it. But let me talk to you before you do it.”

Banks: “It’s a good day to die!”

Brunson: “No, there are people that care. I cared enough to come down here to talk to you.”

Banks: “No, man, they are using you.”

Brunson: “No, I want to be here. If you fire one shot, the police will shoot you, just like you or I would do if we were in the (prison) tower. Take the first step, man. I’ll be there to walk every step with you.”

Banks: “I have problems I can’t deal with. I want to be treated with dignity.”

Brunson: “George, listen man. Everybody needs a crutch sometimes. I’ll be yours. I’ll put my body between you and these men with guns. But you have to trust the man (police).”

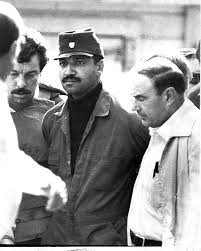

Following the conversation with Brunson, Banks remained silent, contemplating his situation. Finally, four hours after the standoff began, at 11:17 a.m., Banks agreed to come out. He smashed out a rear window in the house and asked that the officers on the scene hold their fire. He was then instructed to hand his weapon to Patrolman Donald Smith through the broken window and surrender himself out the front door of the home into the custody of police. Banks complied.

During an initial search of the home, investigators discovered three 30-round clips and approximately 300 rounds of ammunition. Also noted was that Banks had barricaded all of the windows with furniture and large appliances, and had a mirror set up in order to watch the front and rear doors from a second floor vantage point.

This was a siege like no other in local history. The city of Wilkes-Barre was left in a state of shock following the bloody massacre. Many residents could not understand why Banks, an outwardly stable man, decided to systematically kill 13 innocent human beings for no apparent reason.

Who Was George Emil Banks

George Emil Banks was born on June 22, 1942. Born and raised in Wilkes-Barre, he was the son of a white woman and a black man. Banks’ parents never married and the racial mix seemed to torment him throughout his life. He was educated at St. Mary’s Catholic School, where he was an underachiever, despite having been tested with an IQ of 121. George believed that he was shunned and abused by both whites and blacks throughout his childhood because of his bi-racial status.

“I’ve dealt with racial cowards all my life. A lot of things happened during that time,” said Banks referring to his childhood. “There was this kid named Bones who punched me in the back of the head and kept harassing me just to see if I had enough nerve to fight,” Banks stated.

According to Banks, his problems seemed to get worse as he grew older. During his late teens, racist problems amplified and Banks felt he was constantly harassed. “In 1959, I almost got lynched for drinking a soda and eating a doughnut on a sidewalk.”

While in his early twenties, George saw the military as a possible way of escaping his troubled youth and signed up for a tour of duty in the United States Army. This dream, however, was short lived as he was discharged just two years later in 1961 because he “couldn’t get along with the officers.” Following his “general discharge” from the Army, Banks’ life continued on a downward spiral.

During the early morning hours of September 9, 1961, Banks and two accomplices attempted to rob the Brazil and Roche bar on Pittston Avenue in south Scranton. The crime was doomed from the start. Saloonkeeper Thomas Roche was doing some late night work at the tavern. When confronted by the assailants, Roche refused to cooperate. Angered, Banks pulled out a pistol, shot Roche directly in the chest and fled empty-handed with his two accomplices. Shortly after the tavern robbery, the Wilkes-Barre and Kingston police apprehended the suspects. For his part in the crime, Banks earned a sentence of six-to-fifteen years in prison. He was sent to the State Correctional Institution (SCI) in Graterford, Pennsylvania to serve his time.

In March of 1964, Banks escaped SCI Graterford while on farm detail. Apprehended just three hours later, George received an additional term of one and one-half to five years for the escape. Paroled on March 28, 1969, after serving seven and one-half years behind bars, Banks was now a free man. Following his release, Banks held a number of jobs and married long-time friend Doris Jones, a black woman with whom he had two daughters.

In 1971, Banks acquired a position as a technician with the bureau of Water Quality of the State Department of Environmental Resources (DER) regional office in Wilkes-Barre. The job was the most notable one George had ever held and paid quite well. Banks filed a request in 1974 for commutation of the maximum term of his sentence. Former Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp granted the release, thereby ending Banks’ days on parole.

Perpetual domestic arguments and continued infidelity on George’s part caused him and his wife to separate in 1976. Doris took the children and moved to Ohio. Surprisingly, it was George not Doris who filed for the couple’s ultimate divorce.

The Strange Lifestyle of George Banks

Following the separation with Doris, Banks purchased a home at 28 Schoolhouse Lane in Wilkes-Barre and began to accumulate a harem of girlfriends. All were white, at least ten years younger than Banks, and easily manipulated. Some were homeless and saw George as their only way off the streets. George lived a cult-like lifestyle, quickly amassing four girlfriends simultaneously, two of which were sisters. They all lived together and all bore him at least one child.

Regina (Duryea) Clemens, Banks’ first lover, became pregnant prior to Banks’ separation with Doris and had a daughter, Montanzima Banks, in 1976. Sharon Mazzillo moved in with Banks and Clemens shortly after Montanzima’s birth. She had a son, Kissamayu Banks, on October 6, 1976. Regina Clemens’ sister Susan (Duryea) Yuhas moved in with the trio shortly after Kissmayu’s birth. She became pregnant by George the following year and bore a son, Bowendy Banks, in 1978.

Following the births of his children and the added responsibilities brought on by them, Banks’ mental state began to deteriorate. The State Department of Environmental Resources (DER) asked Banks to resign in 1979. “He was an average worker but we came to a mutual agreement that he should leave,” said James Chester, former Regional Director of the DER in Wilkes-Barre. “His work began to suffer because of his personal problems and the bureau thought that it would be best to conclude the relationship.”

Living in a predominately white neighborhood and being involved in a series of interracial relationships brought its own share of problems to Banks’ home. Banks claimed that his white neighbors “intimidated the women and called the children African niggers.” His home was once firebombed. “They attempted to burn my house, smashed several windows, squirted my babies with water when they were in the yard and intimidated the girls and children.” During a separate incident, while standing at the corner of McCarragher and High streets, Banks said “because I was walking on the sidewalk they hit me with a beer bottle, called me racist names and chased me down the street. I had to grab a pipe to hold them off until police came. Before it was over, about 100 spectators had gathered to watch the whole thing.”

“This is the kind of thing I have had to live with my entire life,” Banks said. “They behave in a cowardly fashion. They look down their nose at me, but they’re out there abusing innocent people who have nothing to do with this. They’re out there damaging my property and harassing my family.”

A former neighbor, Lester Scoble said, “He (Banks) didn’t want nobody to bother him. He didn’t want our kids to play in his yard. He didn‘t like them (Banks’ girlfriends) talking to other people. I don‘t even think any of them went out. I guess they all were one-man women.”

In 1980, despite Banks’ prior arrest record, he obtained a job as a prison watchtower guard at the State Correctional Institute in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania. Dorothy Lyons, moved in with the growing family. She brought along her daughter from a previous marriage, Nancy Lyons, age nine. Within months Dorothy was pregnant by Banks and on January 25, 1981 gave birth to a son, Foraroude Banks. Shortly after Foraroude’s birth, Susan Yuhas had a second child by Banks, a daughter, Mauritania Banks. Sharon Mazzillo, tired of Banks and his growing harem, left the Banks’ household and moved in with her mother a short time later.

George Emil Banks

Mayhem

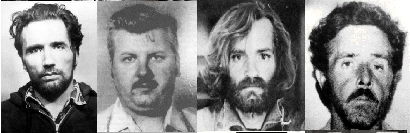

George’s mental state continued to worsen in late 1981. He had obtained a mail-order ordination from the Universal Life Church; however, he became angry after being rejected for religious tax exemptions by the state and picketed city hall in rebuttal. He began to keep a meticulous diary of his thoughts and ideas. He compiled his own list of heroes, including cult leaders Jim Jones, who directed a mass suicide; Charles Manson, who orchestrated a mass murder; and serial killer John Gacy. Banks also had begun to collect survivalist magazines and news accounts on murder and racism. Perhaps the most ominous of all his new hobbies was his desire to build a stockpile of guns and ammunition. A former neighbor stated that Banks “read paramilitary magazines like Solider of Fortune, had books about making bombs, and talked frequently about starting a war.”

By the summer of 1982, Banks had begun talking to fellow guards at work about committing mass killings, preparing his children for warfare, and going into the watchtower and blowing his brains out. Upon learning this, on September 6, 1982 prison officials sent Banks home on extended sick leave to seek psychiatric help. Camp Hill authorities then contacted Luzerne-Wyoming County’s Mental Health-Mental Retardation Center in Wilkes-Barre, requesting assistance for Banks. They scheduled a psychiatric evaluation for September 29, 1982. Kenneth Robinson, a former spokesman for Camp Hill, stated, “He was removed and put on sick leave by the institution as a reaction to the incident (suicide threat).”

By September 24, 1982, George was teetering on the breaking point. He was bitter over his forced leave from work, and even more so by the custody dispute he was having with Sharon Mazzillo over Kissamayu Banks. He wanted full control and custody over the child and was angered that Sharon would not comply. Banks had told the judge during a preliminary custody hearing that, “she (Sharon) can come and see him anytime she wants, I just want the ultimate control over his future, as far as his education and stuff is concerned.” Judge Chester B. Muroski ruled that Banks would retain custody of the child with liberal partial custody granted to Sharon. However, even after the ruling that made Banks the child’s primary care giver, Sharon would not comply with the order and kept the child to herself. By the early morning hours of September 25, George Banks, waking from a self-induced drunken/drugged haze, lost whatever control he had left.

Madness to Mass Murder

Not until Banks was in custody at Wilkes-Barre police headquarters did most of the officers that were on the scene feel the impact of what had occurred. “I looked at him, handcuffed to a chair,” former Chief Detective Jim Zardecki recalled, “and I felt like a balloon that had suddenly been pricked. I started to quiver. My eyes watered. I thought, what really happened here? My God, what happened? Until then, we’d been reacting. We hadn’t time to think about it. We were more lucky than good. He could have blown anybody away.”

Following his arrest, Banks told investigators that he “wanted to die,” and that if he had known for certain his children were dead, he would have stuck the rifle into his mouth and blown himself away. George avoided direct questions about the murders, although he did admit to them. He was uncertain as to how many he had actually committed. Most of the time police questioned him, he ranted about racism and discrimination rather than his crimes.

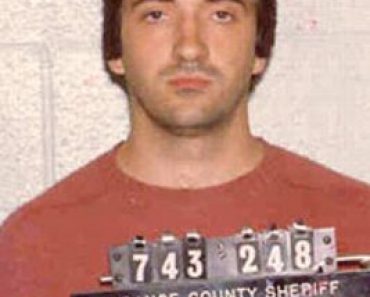

Shortly after 4:00 p.m., Banks was arraigned before District Magistrate Joseph Verespy and charged with five counts of criminal homicide, with other charges to be filed later in the week. Verespy ordered Banks be held without bail in the Luzerne County Prison to await a preliminary hearing scheduled for October 6, 1982. Banks remained calm and motionless during the entire proceeding.

After just a few days in the county lockup, Banks began threatening others and talking about suicide. During one altercation with a prison guard, Banks warned, “I’ve already killed seven people. One more body won’t make a difference.” Following the incident, a prison official placed Banks on a round-the-clock suicide watch. Not permitted to interact with other inmates or participate in any prison activities, Banks’ depression deepened.

Attired in a tan coat and dark trousers, Banks appeared before District Justice Robert Verespy for his preliminary hearing in early October. Banks, with tears streaming down his face, entered pleas of “not guilty” to 13 counts of aggravated murder; two counts of robbery; and one count each of the following: attempted murder, aggravated assault, recklessly endangering another person, and theft. Following the plea, Banks requested a jury trial to determine his ultimate fate.

On January 15, 1982, Dr. Anthony Turchetti examined Banks at the request of the defense and deemed him fit to stand trial. “He (Banks) can understand the nature of criminal proceedings and can assist in his own defense,” Turchetti’s report stated. Following Banks’ request for a change of venue, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court on February 26, 1983 ordered that the jury for Banks trial to be selected from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, approximately 250 miles from Wilkes-Barre. Jury selection began on May 23, 1983, and was completed just four days later with five men, seven women and six alternates.

Unmask The Devil

On June 6, 1983, at approximately 9:15 a.m., the trial for accused mass murderer George Banks began at the Luzerne County Courthouse behind locked doors. A prosecution team consisting of District Attorney Robert Gillespie and Assistant District Attorneys Lawrence Klemow and Michael Bart was chosen to represent the state. Public Defender Basil Russin and two assistants, Joseph Sklarosky and Al Flora, Jr., were present to represent Banks.

The prosecution had many advantages during the trial: Banks’ partial confession, the murder weapon, over 100 photographs of the victims, and more than 40 witnesses. Banks’ attorneys, against their client’s wishes, had prepared an insanity defense and planned to bring up Banks’ peculiar lifestyle and abnormal behavior.

One of the first to testify was Dr. Michael K. Spodak, a psychiatrist for the defense. Spodak testified that during his first interview with Banks, the defendant appeared paranoid, delusional, and suicidal. Throughout that interview, Banks indicated to Spodak that he was a victim of a conspiracy in which the district attorney, judge, police, defense attorneys, and city officials were involved. During the cross-examination, Gillespie asked Spodak if he felt Banks was faking a mental disorder. Spodak replied, “I have confidence he was not trying to be deceptive in the interview.”

During the trial, Banks continued to insist that he was not mentally ill and demanded to testify. Banks’ attorneys worried that the jury would consider him sane if he testified. Still, Banks ignored them and took the stand, saying his testimony was the only chance he had “to pull the mask off the devil.”

George Emil Banks

Sometimes standing, sometimes sitting, Banks coolly and comfortably launched into a rambling, disjointed account of the night of the killings. He voiced his opinion that the police, in a racist conspiracy against him, fired the fatal bullets into some of the victims after he had left them wounded. To prove this theory, Banks wanted to exhume the bodies of the victims for forensic examination. Then he showed the jury the gruesome photographs of the victims, photographs that his attorneys had fought to keep out of the jury’s view. The pictures, Banks said, would “prove my theory of a police conspiracy.” During Banks’ testimony, Assistant Public Defender Al Flora, Jr., lowered his head and wept in frustration.

Before wrapping up, the defense called upon Banks’ mother, brother, and religious adviser, in an attempt to show the jury that George was, in fact, suffering from mental abnormalities, and did not understand the consequences of his actions. This testimony, however, came a little too late following Banks’ own damaging admissions to the jury.

When it came time for the prosecution to present its side, James Olsen, sole survivor of the bloody shooting spree was called to the stand. Olsen testified that George Banks was the man that shot him on September 25, 1982 and left him for dead. Following Olsen’s testimony, the prosecution called detectives and medical examiners to further strengthen the case against Banks. Each detective present at the crime scenes came forward and recounted his/her version of the events. At one point, County Coroner Dr. George Hudock, Jr., while describing the murder scene, said, “I’m still sick to my stomach.”

The Trial

On June 21, 1983, closing arguments in the case began. Attorney Sklarosky, presented his arguments to the jury in a voice hardly audible at times, displayed particular emotion in addressing the panel, and pointed out that the defendant was in store for numerous restless nights and horrible memories during the balance of his lifetime. The defense lawyer noted “the terrible crimes committed by Banks,” but reminded the jury that the defendant “was, and still is, very sick.” Sklarosky challenged the jury to display courage, remembering the fact that, “One person can save his (Banks’) life.”

District Attorney Gillespie countered the defense’s passionate appeal with unemotional arguments. The prosecuting attorney focused the jury on the legal issues, arguing that the evidence showed three possible aggravating circumstances. First was Banks’ prior record; second, his actions endangered others at the time of the killings; and last, that not one, but 13 intentional murders took place at his hands. Gillespie said the evidence showed a “significant history” of violent crimes, stating, “He has graduated now. He no longer assaults with intent to kill. He kills 13 times.”

Following arguments by the attorneys, Judge Toole instructed the jurors for 25 minutes before releasing them for deliberations. The jury of eight women and four men wasted little time in reaching their verdict. George Banks was found guilty of 12 counts of first-degree murder, one count of third-degree murder, attempted murder, aggravated assault, and one count each of robbery, theft, and endangering the life of another person. Banks said nothing as the jurors, polled individually by request of the defense, affirmed their vote. Following the verdicts, Judge Toole set sentencing for the next day and adjourned the court.

June 22, 1983, Banks, on his 41st birthday, waited in his cell for the jury to decide his fate. As the day wore on, reporters, broadcasters, and spectators kept a vigil. Among those in attendance was Raymond Hall, Sr., the father of victim Raymond Hall, Jr. “Nothing’s going to help us with what we’ve lost,” said the elder Hall as he waited to hear the verdict.

The Verdict

After just five and half hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their verdict. Banks stood emotionless and expressionless as the jury foreman spoke, “We the jury find that the defendant, George Emil Banks, has committed state or federal offenses for which a life or death sentence can be imposed.” The foreman then read aloud the jury’s decree that Banks was to die by execution. As was done the previous day, the jurors were polled individually by request of the defense, affirming their votes. As the second jurist, a 24-year-old woman, affirmed her vote, she was overcome with emotion. Following her statement, Banks blurted out, “It’s not your fault, ma’am. You were lied to. A two-hour exhumation would clear me.” The young woman sank into the arms of a fellow juror as she took her seat.

Following the jury poll, Judge Toole explained to Banks that the sentence would be reviewed by the Supreme Court as required by law, adding, “I sincerely hope that God has touched you and hopefully God will forgive you for what you have done. From this moment on, your life is in the hands of God and the appellate courts.”

After Banks left the courtroom, Toole told the jury, “The legal journey that you embarked upon has ended. I am sure everyone present, hopefully, understands the pressure and awesome responsibility you have all shouldered.” Judge Toole then said that rather than attempting to express his admiration and gratitude via a lengthy dissertation, he would just say, “Thank you.” He then dismissed the jury.

In the aftermath of sentencing, Al Flora, Jr. stated his reaction, “I think the jury displayed more courage than I ever would have. I’m sure, to them, justice has been served. It’s a decision I will always respect and never second guess.” District Attorney Gillespie appeared to have mixed feelings following the verdict. “There is no great surge of joy when the death penalty is achieved, my heart goes out to the members of the jury. They are the ones that should be congratulated. They truly were courageous,” said Gillespie.

Following the trial, George Banks was remanded to the maximum-security unit of the State Correctional Institute at Huntington where he remained until November of 1985, when he was transferred to the State Correctional Institute at Graterford following a refusal by the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn his verdict.

George Emil Banks remains on death row.

Source: murderpedia | David Lohr | standardspeaker.com | amok.fandom.com

This site contains affiliate links. We may, at no cost to you, receive a commission for purchases made through these links

WickedWe Suggests: